You know the sound. It’s that thumping, primal groan that greets you at every NFL stadium, every European soccer match, and basically every wedding where the DJ has given up on subtlety. It’s the sound of seventy thousand people humming in unison—a monochromatic, seven-note chant that feels like it’s existed since the dawn of time.

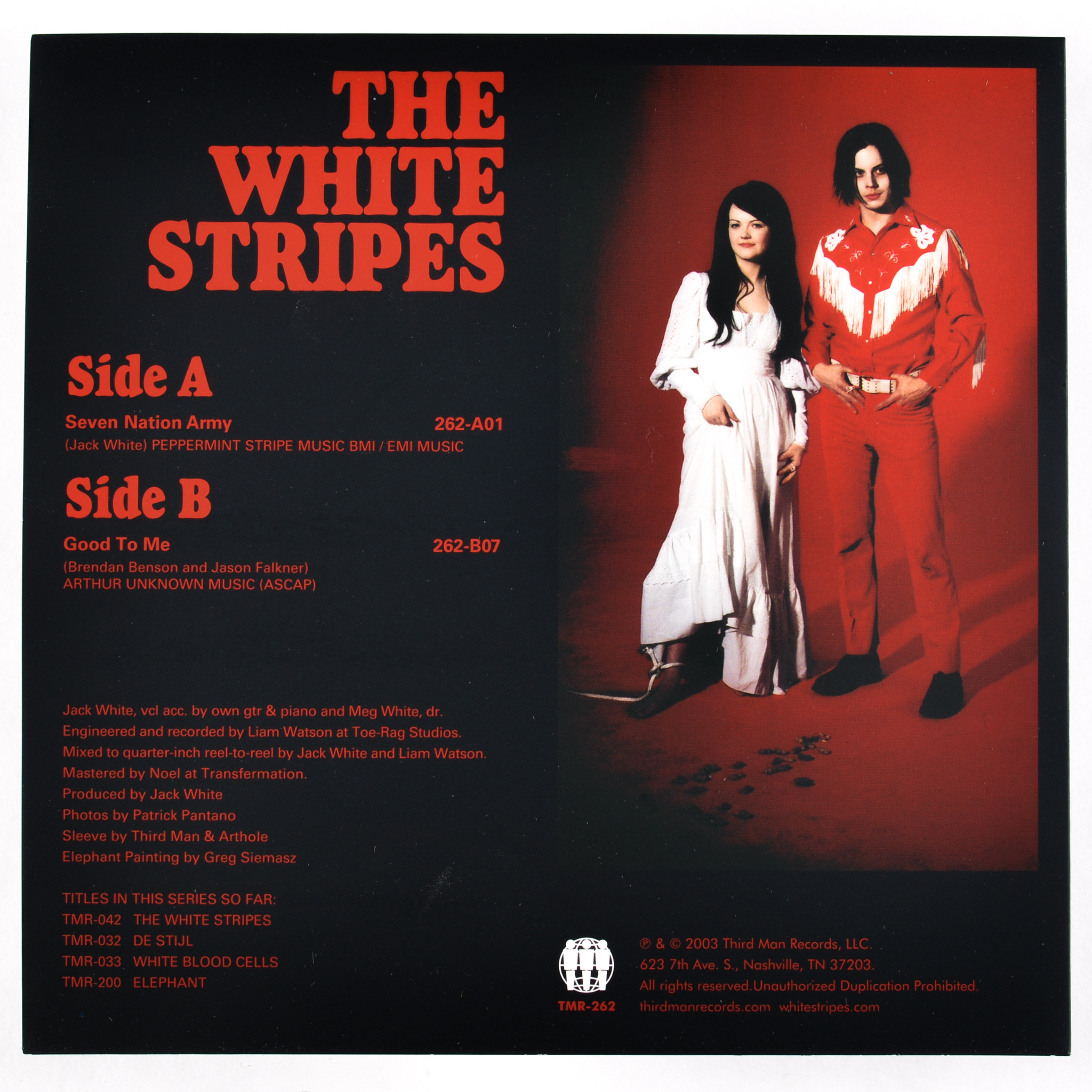

But here’s the thing: Seven Nation Army isn’t a folk song from the 1920s. It’s a track from 2003 that was recorded on an 8-track tape machine using gear that was ancient even when the album Elephant was new.

Jack White didn’t even think it was a hit. Honestly, he was saving that specific riff in his back pocket just in case he ever got asked to write a James Bond theme. He figured that was a long shot, so he used it for a garage rock duo instead. Five years later, he actually did the Bond theme for Quantum of Solace, but by then, his "Bond riff" had already conquered the world.

The Bass Line That Isn't Actually a Bass

If you walk into a guitar shop and see a kid trying out a bass, they’re probably playing this song. It’s the "Smoke on the Water" of the 21st century.

There is one major problem with that. There is no bass guitar on the recording.

The White Stripes famously didn’t have a bassist. It was just Jack and Meg. To get that massive, subterranean growl, Jack used a 1950s Kay hollow-body guitar plugged into a DigiTech Whammy pedal. He set the pedal to drop the pitch by a full octave.

It’s a sonic trick.

That’s why the "bass" sounds so scratchy and raw compared to a real Fender Precision. It’s an electric guitar screaming through a digital shifter, trying to pretend it’s a four-string. When the chorus kicks in and the "real" guitar enters, the octave effect stays on, but it’s layered under the distorted chords. It creates this wall of sound that feels ten times larger than two people in a room should be able to produce.

Technical Breakdown of the Sound:

- The Gear: An 8-track tape machine (no computers allowed).

- The Mic: A duo-mic setup for vocals—one high-quality Neumann and one Shure SM57 running through a small, shitty guitar amp for grit.

- The Tempo: A steady 120 BPM.

- The Key: E Minor (mostly).

What the Lyrics Actually Mean (It’s Not About War)

The title Seven Nation Army sounds like a political manifesto. It sounds like a call to arms.

It’s actually a toddler’s mistake.

When Jack White was a kid in Detroit, he used to mishear "The Salvation Army" as "The Seven Nation Army." He liked the phrase so much he kept it in his head for decades.

The song itself isn't about geopolitical conflict. It’s a paranoid rant about gossip. In 2002, the White Stripes were becoming the "it" band, and the UK press was obsessed with whether Jack and Meg were actually brother and sister or an ex-married couple. The scrutiny was suffocating.

Jack wrote the lyrics as a story about a character who enters a town, hears everyone whispering about him behind his back, and decides to leave. "I'm goin' to Wichita," he sings, referencing a place where he can just "work the straw" and be left alone. It’s a song about the weight of fame and the desire to disappear.

The irony? The song became so famous that Jack can never truly disappear again.

How it Became the World's Biggest Sports Anthem

Most bands would kill for a stadium anthem. The White Stripes got one by accident.

It started in a bar in Milan, Italy. In October 2003, fans of the Belgian club Club Brugge were drinking before a match against AC Milan. The song came on the radio. They started humming the riff. They kept humming it during the game.

It became their "lucky" song.

✨ Don't miss: Chuck Mangione Feels So Good: Why This 1977 Hit Is Still Living Rent-Free in Our Heads

Fast forward to the 2006 World Cup. The Italian national team fans heard the Belgian fans doing it, stole the melody, and turned it into the unofficial anthem of their championship run. From there, it was over. It spread to the Baltimore Ravens, to college marching bands, to political rallies for Jeremy Corbyn, and eventually to the horns of cruise ships.

Jack White has said he feels like he doesn't even own the song anymore. To him, it’s "folk music" now. It’s passed into the public consciousness where people know the melody even if they have no idea who Meg White is.

Why the Production Still Holds Up

Elephant was recorded at Toe Rag Studios in London. It’s a place that famously bans digital technology.

There were no Pro Tools. No pitch correction. No "undo" button.

If Meg hit the floor tom a little too hard, that was the take. This "limitation" is why the song feels so human. In a modern era where everything is quantized to a perfect grid, the slight imperfections in Seven Nation Army make it breathe.

The drums are recorded in mono. That’s almost unheard of for a major rock hit in the 2000s. By keeping the drums centered and narrow, the "bass" riff has more room to breathe on the edges of the mix. It creates a claustrophobic, intense energy that explodes when the cymbals finally crash in the chorus.

Actionable Insights for Musicians and Fans

If you want to capture the "Seven Nation Army" vibe in your own work or just appreciate it more deeply, look at these specific elements:

- Embrace the Octave Pedal: If you're a guitar player in a small band, a pitch-shifter like the DigiTech Whammy or an EHX POG can fill the sonic space of a missing bassist.

- Limit Your Tracks: Try recording with only 8 tracks. It forces you to make decisions rather than endlessly tweaking digital layers.

- The Power of the Wordless Chorus: You don't always need a hook with lyrics. Sometimes a melody that people can "oh-oh-oh" along to is more powerful than the most poetic lines in the world.

- Tension and Release: Notice how the song stays quiet for almost the entire first verse. The snare drum doesn't even enter until halfway through. That patience is what makes the eventual explosion so satisfying.

The legacy of the track isn't just that it’s catchy. It’s a reminder that a great idea—even one written during a soundcheck in Melbourne—doesn't need a million-dollar studio to change the world. You just need a riff that seventy thousand people can't get out of their heads.