It was basically a dot. A tiny, insignificant speck of coral in the middle of a massive blue void. If you look at the Battle of Midway on map today, you realize just how insane it was that two of the world’s most powerful navies managed to find each other at all. Most people think of WWII battles as these crowded, chaotic melees on land. But Midway? It was a game of hide-and-seek played with 20,000-ton toys across thousands of miles of empty saltwater.

Honestly, the scale is what gets you.

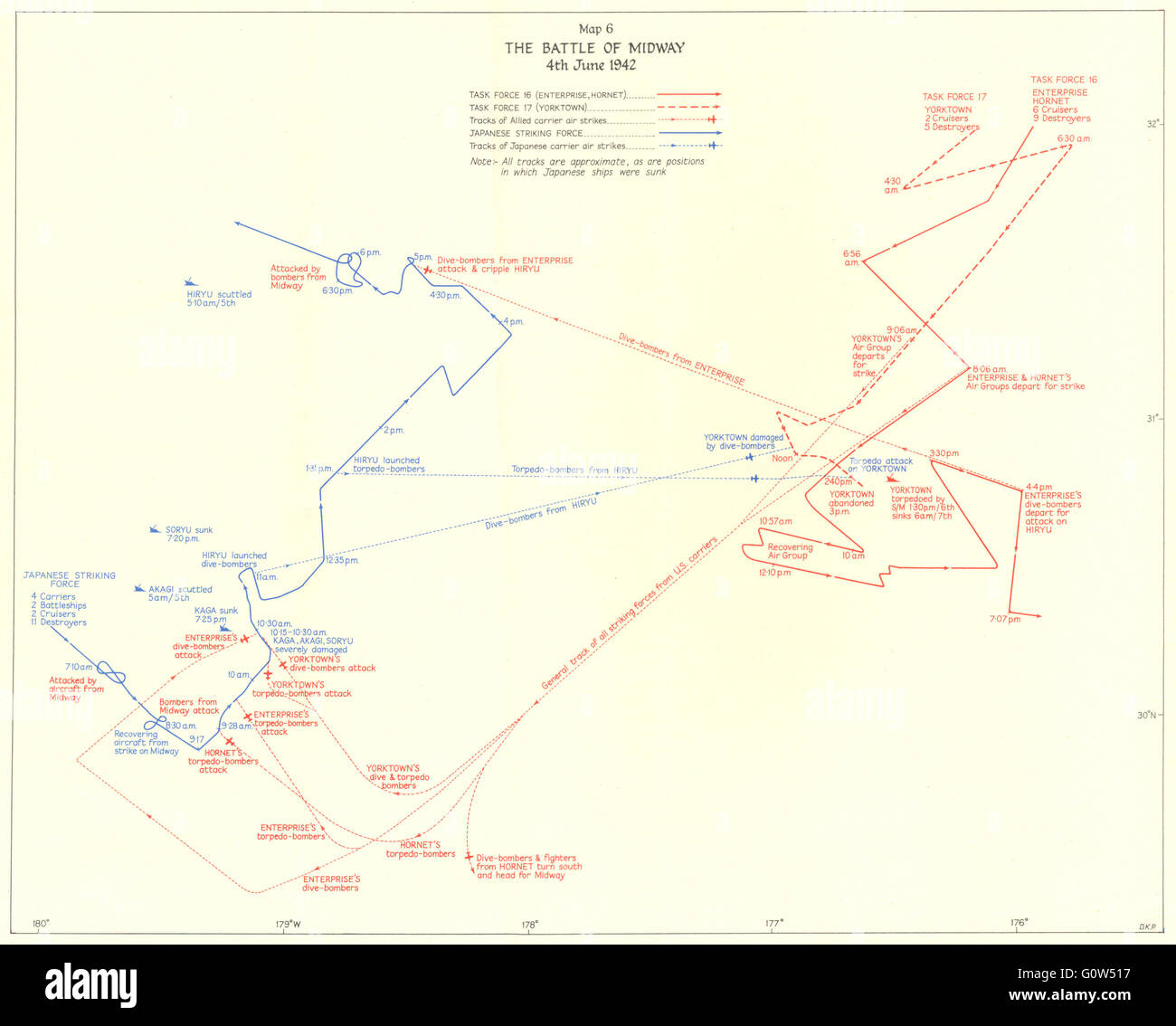

The Japanese Imperial Navy wasn't just coming for a little island. They were trying to lure the American fleet into a "decisive battle" to finish what they started at Pearl Harbor. When you track the Battle of Midway on map layouts from June 1942, you see a sprawling net. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had his forces spread out from the Aleutian Islands down to the central Pacific. He thought he was being clever. He thought he was outmaneuvering an enemy that didn't know he was there. He was wrong.

The Geography of a Trap

To understand why this mattered, you have to look at where Midway actually sits. It is roughly 1,300 miles northwest of Honolulu. That’s it. It’s the last link in the Hawaiian Island chain. If the Japanese took it, they’d have a literal "sentry" sitting on California's doorstep. They could launch bombers from there to hit Pearl Harbor again and again.

The U.S. Navy was in rough shape. We’d lost the Lexington at Coral Sea. The Yorktown was held together with literal spit and prayers (and about 1,400 repairmen working around the clock). When you plot the Battle of Midway on map coordinates, the American carriers—Enterprise, Hornet, and the patched-up Yorktown—were sitting at a spot nicknamed "Point Luck." It was about 325 miles northeast of Midway.

They were waiting.

Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance and Frank Jack Fletcher weren't just guessing. They had the Japanese "playbook" because cryptologists like Joseph Rochefort had cracked the Japanese naval code, JN-25. While the Japanese were sailing toward what they thought was an empty trap, the Americans were already positioned on the flank. It’s the naval equivalent of hiding behind a door with a baseball bat.

✨ Don't miss: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

The Four Minutes That Flipped the World

On the morning of June 4, 1942, the Japanese felt invincible. They had four of the carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor: Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu. These weren't just ships; they were the elite core of the First Air Fleet.

If you look at the Battle of Midway on map movements between 7:00 AM and 10:20 AM, it looks like a disaster for the U.S. Initial American air strikes from Midway island itself were slaughtered. The TBD Devastator torpedo bombers—slow, bulky planes—were picked off like flies by Japanese Zeroes. Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8) lost 15 out of 15 planes. Only one man, Ensign George Gay, survived. He floated in the water, watching the carnage from below.

The Japanese commanders, specifically Admiral Nagumo, were distracted. They were switching bombs for torpedoes and back again. Their decks were cluttered with fuel hoses and stacked munitions.

Then, at 10:22 AM, everything changed.

Three squadrons of SBD Dauntless dive bombers, led by Wade McClusky and Max Leslie, arrived simultaneously from different directions. They had been searching for the fleet and were almost out of fuel. They followed a lone Japanese destroyer, the Arashi, which was racing back to the main fleet.

In less than five minutes, three Japanese carriers were screaming infernos.

🔗 Read more: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

People talk about "turning points" in history like they’re slow rotations. This wasn't. This was a vertical drop. When you trace the Battle of Midway on map vectors for those dive bombers, you see the exact moment the Japanese Empire's westward expansion hit a brick wall. By the end of the day, all four Japanese carriers were gone. The U.S. lost the Yorktown, but the trade-off was a strategic landslide.

Why the Map Doesn't Tell the Whole Story

We often look at these historical maps and see neat little blue and red arrows. It makes it look like everyone knew where they were going. In reality? It was a mess.

Navigation back then was basically math and stars. There was no GPS. There were no satellites. Pilots often got lost and ran out of fuel over the open ocean. If you missed your carrier by even a few miles, you were dead. You’d just fly until the engine sputtered and then ditch in the drink.

There’s also the myth that the Japanese were just "unlucky." Luck played a role, sure. But the Battle of Midway on map success for the Americans was built on intelligence and risk-taking. Admiral Chester Nimitz decided to bet his entire remaining fleet on a single piece of decrypted code. If Rochefort had been wrong about "AF" meaning Midway, the Japanese would have sailed into an undefended Hawaii.

It was a gamble of such massive proportions that it’s hard to wrap your head around today.

The Long-Term Fallout

After Midway, the Japanese could no longer replace their losses. They lost their best pilots—men with thousands of hours of flight time who had been fighting since the invasion of China. You can't just train a replacement for that in a few months.

💡 You might also like: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

The Battle of Midway on map transitions into the "Island Hopping" campaign shortly after. The momentum shifted. The Japanese went from being the hunters to the hunted. They were forced into a defensive posture they never recovered from.

We see the Pacific as a series of battles—Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Okinawa. But Midway was the pivot. It was the moment the "Greatest Generation" proved that a battered, bruised navy could outthink and outfight a superior force through sheer grit and better data.

Navigating the History Today

If you’re trying to visualize this for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, don't just look at a static image. You need to look at the "time-lapse" of the Battle of Midway on map layouts.

- Check the morning scouts: Look at the search patterns of the PBY Catalinas. They were the ones who spotted the Japanese "Main Body" first.

- The "Flight to Nowhere": Look at the path of the Hornet's air group, which missed the battle entirely because they flew the wrong heading. It shows how close this came to being a disaster for the U.S.

- The Hiryu’s Counterattack: Trace the path of the lone remaining Japanese carrier as it desperately tried to even the score before being sunk itself.

The best way to respect this history is to realize how fragile the victory was. It wasn't inevitable. It was won by guys in their early 20s who were terrified, low on fuel, and staring down the most feared navy on the planet.

To truly grasp the strategic weight of this conflict, start by layering the Japanese expansion limits of May 1942 over a modern map of the Pacific. You'll see that they were at the absolute limit of their logistics. Every mile further east was a mile closer to their collapse.

Study the "Point Luck" coordinates ($32^{\circ} \text{N}, 173^{\circ} \text{W}$) and compare them to the Japanese approach from the northwest. The intercept wasn't a head-on collision; it was a perfect T-bone. Understanding those angles is the only way to understand how the U.S. won a battle they had no business winning.

Stop looking at Midway as a victory and start looking at it as a miracle of intelligence and timing. Visit the National WWII Museum's digital archives or the Naval History and Heritage Command's website to see the actual hand-drawn charts used by the commanders. Seeing the coffee stains and the frantic pencil marks on those maps makes the history feel a lot more real than a textbook ever could.