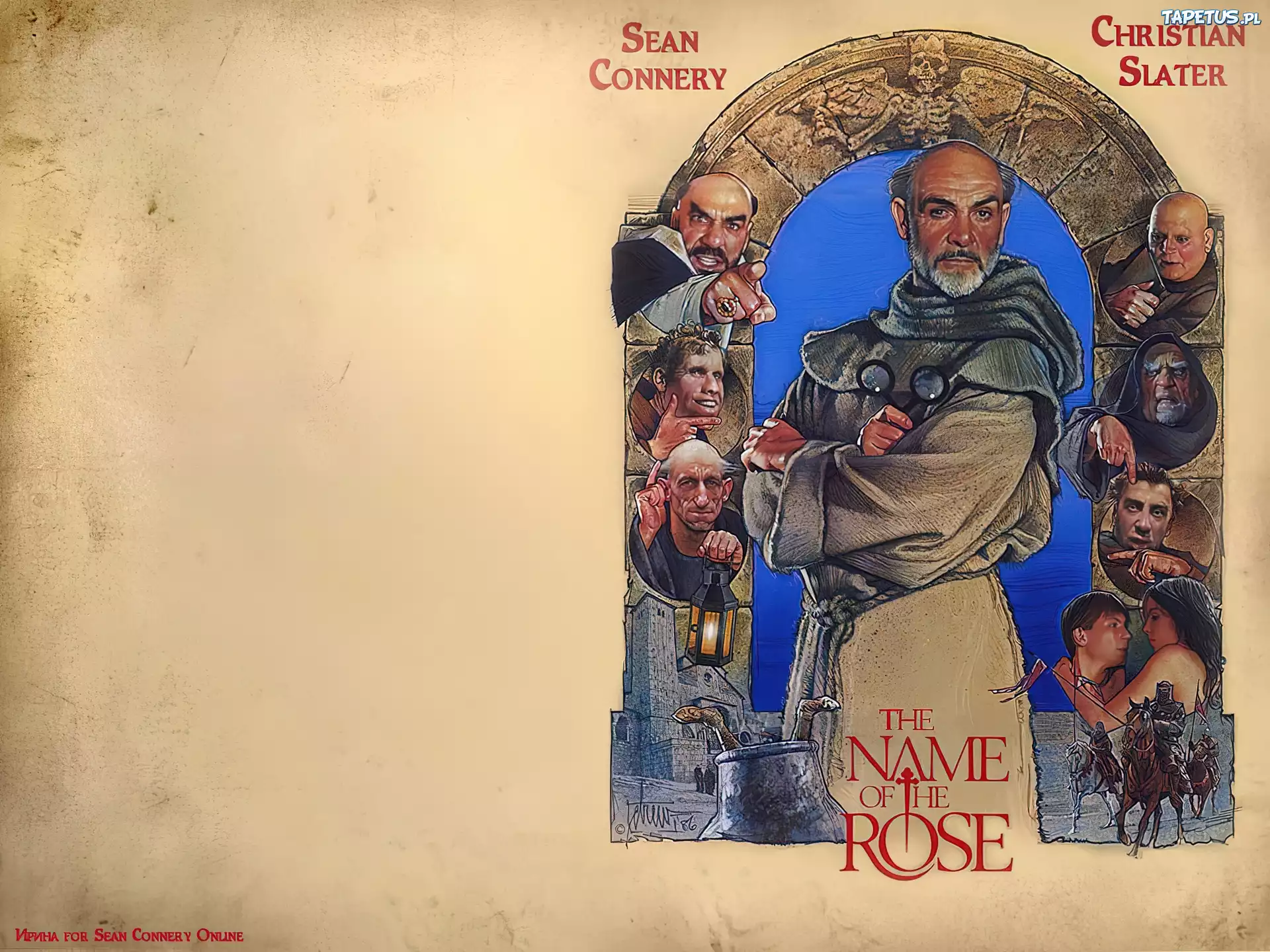

Sean Connery was basically box office poison in the mid-1980s. It’s hard to imagine now, looking back at his legacy, but before he stepped into the monks' robes for The Name of the Rose, his career was sort of drifting in the wind. He’d tried to break away from the shadow of 007, but audiences weren't buying it. When Jean-Jacques Annaud started looking for his William of Baskerville, Connery wasn’t just at the bottom of the list—he wasn't even on it.

The studio hated the idea. Columbia Pictures actually pulled out of the project because they thought putting Sean Connery in a medieval mystery was a recipe for financial disaster. They were wrong. Really wrong.

The Monk Who Saved a Career

Umberto Eco’s novel is a beast. If you've ever tried to slog through the Latin passages and the dense semiotics, you know it’s not exactly a "beach read." Translating that into a film required a lead who could carry the intellectual weight of a Sherlock Holmes-style detective while looking like he actually belonged in a damp, 14th-century Italian monastery.

Annaud looked at everyone. He reportedly considered Robert De Niro, but De Niro wanted the film to feature a duel between William and the Inquisitor. That didn't fit the vibe. He looked at Michael Caine. He looked at Richard Harris. Then Connery showed up.

He had this presence. It wasn't the suave, tuxedo-wearing Bond energy anymore; it was something weathered and deeply intelligent. When he put on the heavy wool habit, he became William of Baskerville. Honestly, the way he uses his voice in this film—that distinct Scottish burr softened into the cadence of a scholar—is probably some of his best work. It’s subtle. It’s sharp. It feels real.

Behind the Scenes of the Aemilian Abbey

They didn't just find a random castle and start shooting. The production of The Name of the Rose was an architectural nightmare in the best way possible. They built the exterior of the massive, looming abbey on a hilltop outside Rome. It was the largest exterior set built in Europe since Cleopatra.

The interior, though? That was different.

To get that authentic, claustrophobic, "everything is covered in soot" feeling, they filmed in the Eberbach Abbey in Germany. If the walls look cold in the movie, it’s because they were. The cast was freezing. You can see the breath of the actors in several scenes, and that wasn't a special effect. It adds a layer of grime and reality that modern CGI just can't replicate.

Christian Slater was only about 15 or 16 during filming. Think about that for a second. You’re a teenager from New York, and suddenly you’re thrust into a medieval nightmare landscape opposite a living legend who is famously... well, intense on set. Slater has mentioned in various retrospectives that Connery was professional but demanding. He didn't suffer fools. If you didn't know your lines, you were going to hear about it. This dynamic actually translated perfectly to the master-apprentice relationship between William and Adso.

The Mystery of the Labyrinth

One of the coolest parts of the movie is the library. In Eco’s book, it’s this impossible, mathematical maze designed to protect dangerous knowledge. In the film, they had to make it visual. They built this multi-layered, Escher-like structure that honestly looks like it could drive a person insane.

The lighting is the secret sauce here. Tonino Delli Colli, the cinematographer who worked with legends like Pasolini and Fellini, used a lot of natural-looking light sources. Torches. Small windows. It makes the library feel like a character itself—something ancient and hungry that wants to keep its secrets.

The plot, for those who need a refresher, centers on a series of "impossible" murders at a Benedictine monastery. Monks are turning up dead in vats of pig blood or slumped over desks. The monks think it’s the Apocalypse. William, being a man of logic, thinks it’s a human being with a motive. It’s essentially a 14th-century CSI, but with more heresy and much worse hygiene.

Why the Critics Were Split

When it came out in 1986, the American critics were kind of "meh" about it. Roger Ebert famously gave it a lukewarm review, complaining that the plot felt muddled. But Europe? Europe went absolutely wild for it. It was a massive hit in Germany, France, and Italy.

✨ Don't miss: Netflix's The Residence Cast: Who Is Actually In This Shonda Rhimes Murder Mystery

Maybe it’s because European audiences were more familiar with the historical weight of the Church’s power. Or maybe they just liked the "grotesque" aesthetic. The casting of the monks is legendary for finding the most unique, weathered, and—let’s be honest—terrifying faces in Europe. They didn't go for Hollywood handsome. They went for "looks like he hasn't seen sunlight or a toothbrush in forty years."

The makeup work on F. Murray Abraham as the Inquisitor Bernardo Gui is also worth mentioning. He played the villain with such a cold, bureaucratic detachment that it’s actually scarier than a screaming madman. He represents the institutionalized power that doesn't care about truth, only about order.

The Lasting Legacy of Sean Connery’s William

This film was the turning point. After The Name of the Rose, Sean Connery was suddenly a "serious" actor again. It paved the direct path to him winning an Oscar for The Untouchables just a year later. It proved he could lead a film that wasn't an action thriller.

The movie also managed to preserve the core philosophical debate of the book: the danger of taking any idea too seriously. The killer’s motive—which I won't spoil if you somehow haven't seen it—is entirely about the power of laughter. It’s about whether God can laugh, or if laughter is a tool of the devil to undermine faith. It’s a pretty deep concept for a movie that also features a giant library fire and a guy getting crushed by a building.

The film holds up because it feels tactile. You can almost smell the old parchment and the damp stone. In an era where everything is smoothed out by digital filters, the grit of this production is refreshing.

📖 Related: Spenser: For Hire TV Series: What Most People Get Wrong

How to Appreciate the Film Today

If you’re going to revisit it, keep a few things in mind to get the most out of the experience.

- Watch the background. The "grotesques"—the actors playing the background monks—were chosen specifically to mimic medieval art. Every face tells a story of poverty or religious obsession.

- Listen to the score. James Horner’s work here is haunting. He uses synthesizers mixed with medieval-sounding chants, creating a vibe that is both ancient and slightly "off," which fits the mystery perfectly.

- Focus on the logic. William of Baskerville uses "semiotics"—the study of signs. Watch how he observes things like footprints or the way a robe hangs. It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling.

- Check the history. While the story is fictional, the conflict between the Franciscans and the Papacy over "the poverty of Christ" was a real, historical flashpoint that nearly tore the Church apart.

To really dive deep into the world of William of Baskerville, compare the film's ending to the book's. They are significantly different. The book is much bleaker, while the movie gives you a bit more of a traditional "cinematic" resolution. Both have their merits, but seeing how Annaud chose to adapt Eco's complex philosophy into a 2-hour thriller is a lesson in filmmaking itself.

The next step for any fan is to track down the 2019 miniseries starring John Turturro. It has more room to breathe and includes many of the subplots the movie had to cut. However, for sheer atmosphere and the definitive "William," the 1986 version remains the gold standard.