Look at a picture of a beach. It’s probably beautiful. But if you’ve spent any time looking at sea level rise photos lately, you might notice something weird. Sometimes the water looks like it’s swallowing a city, and other times, it just looks like a high tide on a Tuesday.

The reality of documenting climate change is messy.

Honestly, the internet is flooded with "disaster porn." You know the type. Photoshopped waves crashing over the Statue of Liberty or CGI renders of Miami underwater that look like a scene from a Roland Emmerich movie. It’s catchy. It gets clicks. But it’s not really helpful for understanding what’s actually happening to our coastlines right now.

Real sea level rise photos are often boring. They’re photos of "sunny day flooding" in Charleston or a cracked sidewalk in the Marshall Islands. They aren't always dramatic. They are persistent.

The Trouble With Visualizing a Slow Motion Disaster

The ocean doesn't just "rise" like a bathtub filling up. It creeps.

If you talk to photographers like Kadir van Lohuizen, who has spent years documenting this for his "Where Will We Go?" project, he’ll tell you that the challenge is capturing the process, not just the event. He’s traveled from Kiribati to Fiji to the Netherlands. What he captures isn't always a wall of water. Often, it's just a guy in Jakarta trying to raise the floor of his house for the third time in ten years.

That’s the nuance.

Scientists at NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) point out that global sea levels have risen about 8 to 9 inches since 1880. That sounds like nothing. But when you look at sea level rise photos from places like the Chesapeake Bay, those few inches mean the difference between a farm being productive and a farm being a salt marsh full of "ghost trees."

👉 See also: How Old Is Celeste Rivas? The Truth Behind the Tragic Timeline

Those bleached, dead trees are one of the most haunting visual markers we have. They died because saltwater seeped into the soil and poisoned their roots. It’s a slow-motion drowning. You don't need Photoshop to make that look scary.

High Tide vs. The New Normal

We have to talk about the "King Tide" projects.

Groups like the Witness King Tides project encourage regular people to take sea level rise photos during the highest tides of the year. Why? Because the King Tide of today is basically the average high tide of 2050. It’s a preview.

If you see a photo of a street in Miami Beach during a King Tide, you’ll see saltwater bubbling up through the storm drains. The water isn't coming over the sea wall; it's coming from underneath the city because Florida sits on porous limestone. You can’t build a wall to stop that.

- In Norfolk, Virginia, residents have an app called "Sea Level Rise" to crowdsource flood data.

- Photos from these apps help city planners figure out which roads to raise first.

- It's less about art and more about survival.

Sometimes, the best sea level rise photos are the ones that compare the same spot over fifty years. The State Library of Queensland in Australia has some incredible archives. You look at a beach from 1920 and then the same spot in 2024. The dunes are gone. The houses are closer. The margin for error has disappeared.

Why Most Viral Images Are Basically Fake

Be careful with what you share.

There’s a famous photo that makes the rounds every few months showing the Statue of Liberty in 1900 versus today, claiming the water hasn't moved. It’s a favorite for skeptics. But it’s a bad faith argument. Sea level rise isn't measured by looking at a giant rock from a mile away with a telephoto lens. It’s measured by tide gauges and satellite altimetry.

✨ Don't miss: How Did Black Men Vote in 2024: What Really Happened at the Polls

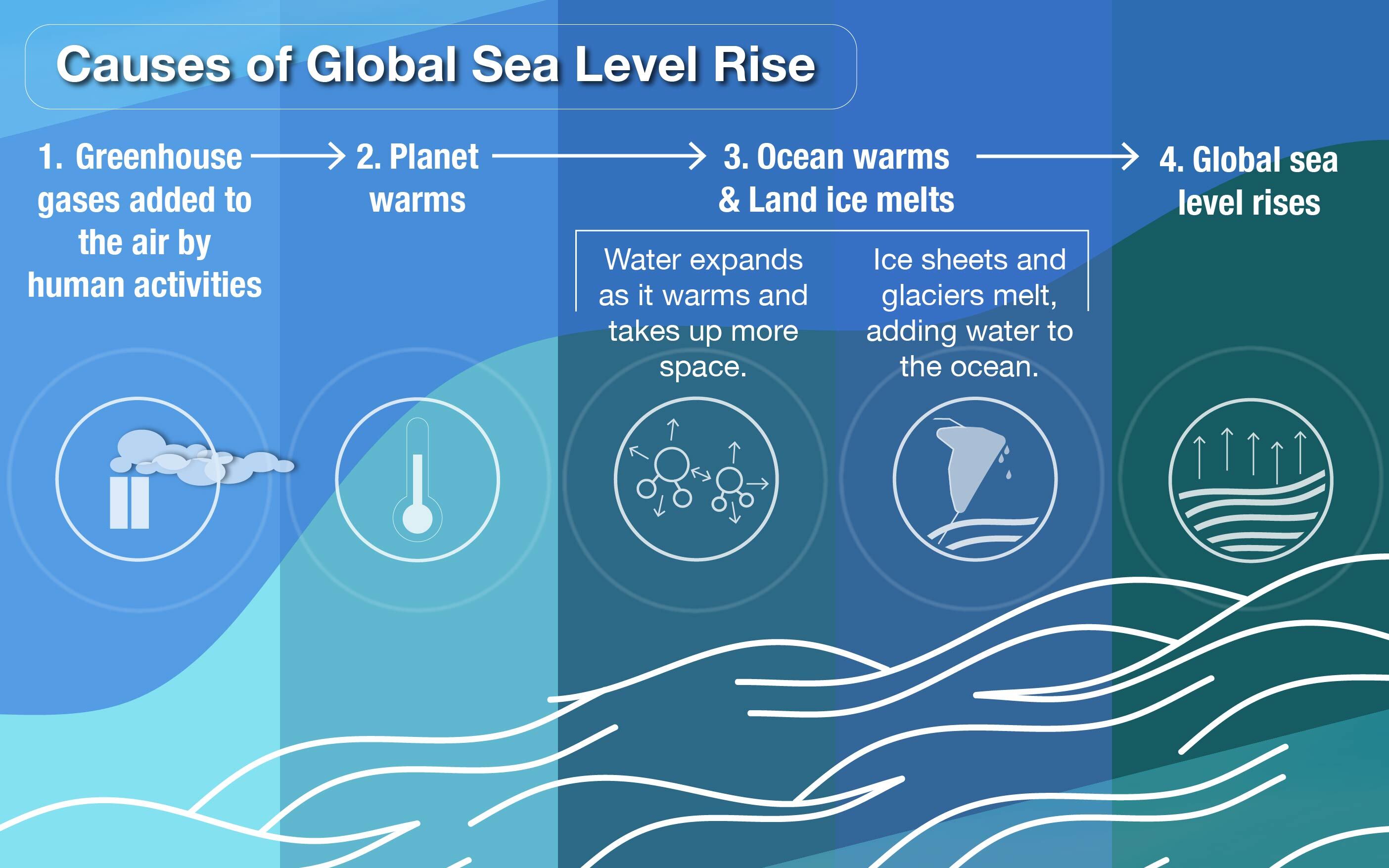

Satellites like Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich are the real MVPs here. They measure the ocean's height down to the millimeter. While a photo can show you a flooded park, the satellite data shows you the thermal expansion of the water. As the ocean warms, it expands. It's basic physics.

$V = V_0(1 + \beta \Delta T)$

Basically, the warmer the water gets, the more space it takes up. You can't see "thermal expansion" in a single snapshot, but you can see the results when a storm surge hits a coastline that is already sitting higher than it used to.

The Human Side of the Lens

The most effective sea level rise photos focus on people.

Think about the images coming out of the Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana. This isn't just about water; it's about the first "climate refugees" in the United States. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe has seen their island shrink from 22,000 acres to a tiny strip of land barely 320 acres wide.

When you see a photo of a family packing up a house they've lived in for five generations, the "sea level" part of the photo becomes secondary to the "loss" part.

What You Should Actually Look For

If you’re trying to find or take accurate sea level rise photos, you need to look for context.

🔗 Read more: Great Barrington MA Tornado: What Really Happened That Memorial Day

- Check the tide charts. Is the photo taken during a storm? A King Tide? Or just a normal day? A flood on a sunny day is way more significant than a flood during a hurricane.

- Look for infrastructure markers. Are there "No Wake" signs on residential streets? Are there pumps being installed?

- Saltwater intrusion. Look for dead vegetation or "ghost forests." This is the "hidden" side of sea level rise that happens underground long before the waves reach the front door.

- The "Before and After." Single photos are anecdotes. Pairs of photos are data.

Mapping the Future

We're getting better at visualizing this. Organizations like Climate Central have created tools that overlay sea level rise projections onto Google Earth images. It’s sort of a hybrid between a photo and a map.

You can toggle a slider to see what 2 degrees Celsius of warming does to London, Shanghai, or New York. It’s terrifying because it’s familiar. Seeing the South Street Seaport underwater in a photorealistic render hits different than looking at a graph with a blue line pointing up.

But we have to be careful with these tools. They are models, not memories.

Actionable Steps for Documenting Your Own Community

You don't need to be a National Geographic photographer to contribute to the record. In fact, local sea level rise photos are often more valuable for city councils and local engineers than professional shots.

- Join a Citizen Science project. Look up the "MyCoast" app or local King Tide initiatives. They provide specific instructions on how to take photos that scientists can actually use.

- Find a fixed point. If you live near the water, pick a specific landmark—a pier piling, a sea wall, or a specific rock. Take a photo of it once a month at high tide. Over five years, you’ll have a personal record that means more than any stock photo.

- Document the "nuisance." Don't wait for the big storm. Take photos of the large puddles that don't go away or the drains that are backed up when it hasn't even rained. That's the real story of sea level rise in the 2020s.

- Label everything. A photo without a date, time, and location is just a pretty picture. If you want your sea level rise photos to matter, metadata is your best friend.

The ocean is moving. It’s shifting the boundaries of where we can live and where we can’t. Photos are the only way we have to make that shift visible to people who don't live on the coast. But we have to make sure we're showing the truth, not just the drama.

Stop looking for the big wave. Start looking for the water in the street where it shouldn't be. That’s where the real story is.

If you want to see the most accurate current data, check the NOAA Tides and Currents portal. They have live cameras and gauge data that show the reality of coastal changes in real-time. It’s not always "photogenic," but it’s the truth.

Start by checking your own local flood maps. Most people are surprised to find out how much "100-year flood plains" have shifted in just the last decade. Documenting these changes now ensures that future generations understand exactly how the landscape began to change under our feet.

The best time to start taking these photos was twenty years ago. The second best time is today. High tide is at 4:00 PM. Go see what it looks like.