Steven Soderbergh didn't just make a movie about stripping. Honestly, when people think about scenes from Magic Mike, they usually default to Channing Tatum’s "Pony" routine or that gold-spray-paint moment. It’s iconic. But the reality of the 2012 film—and the sequels that followed—is way grittier and more technically complex than the TikTok clips suggest. It’s actually a movie about the Great Recession. It’s about a guy trying to get a loan for a custom furniture business while selling his body to make ends meet.

The choreography is the hook, sure. However, the legacy of these films rests on how they navigated the line between objectification and genuine artistry.

The Anatomy of the Most Influential Scenes from Magic Mike

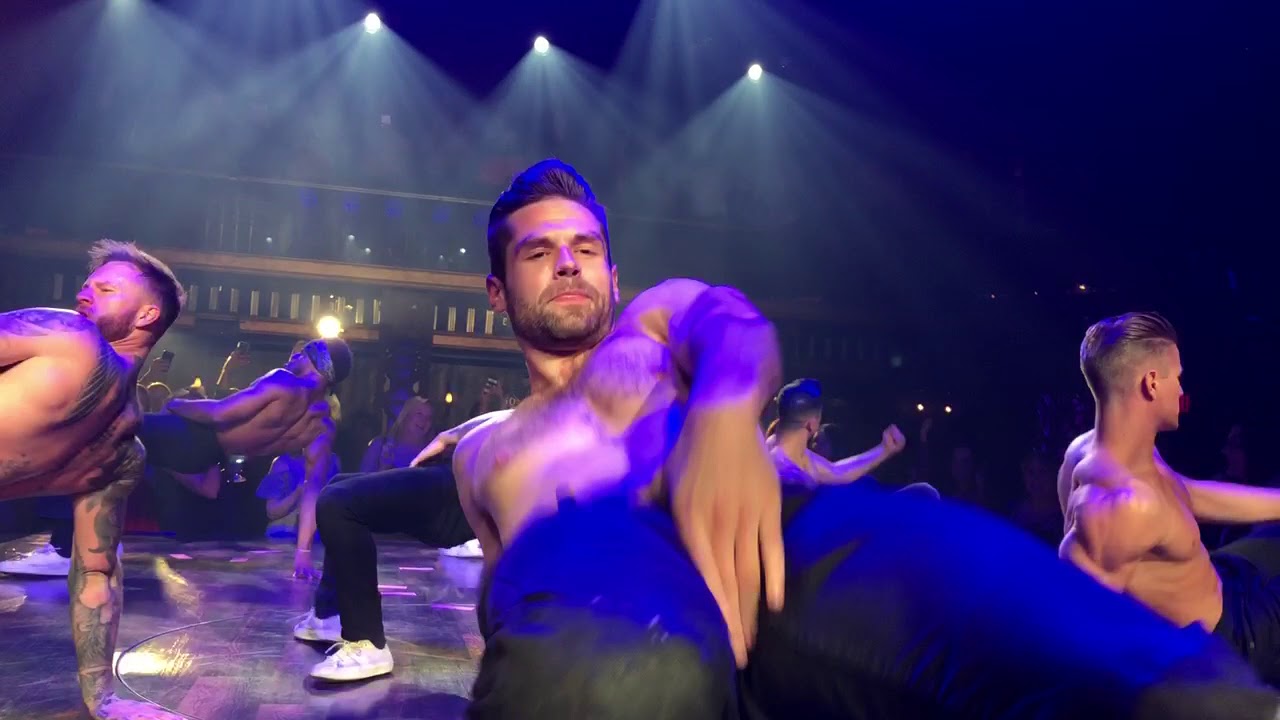

Let’s talk about the "Pony" sequence. It’s the gold standard. In the first film, Mike (Channing Tatum) takes the stage to Ginuwine, and it’s a masterclass in physical comedy mixed with high-level breakdancing. Tatum, who actually worked as a stripper in Tampa before his Hollywood break, isn't just "dancing." He’s using floorwork that requires insane core strength. He’s reacting to the crowd. Most scenes from Magic Mike work because they feel lived-in. Soderbergh used a specific yellow-tinted color grade for the club interiors that made the air look thick with sweat and cheap cologne. It felt real.

Contrast that with the "It’s Raining Men" group number. It’s campy. It’s theatrical. Big Dick Richie (Joe Manganiello), Ken (Matt Bomer), and Tito (Adam Rodriguez) are all playing archetypes. Firemen. Construction workers. It’s the fantasy. But then the camera cuts to the backstage area—the "Xquisite" dressing room—and you see the guys taping their outfits together. This duality is what people miss. The glamour is a facade.

Why the Convenience Store Scene Changed Everything

If you ask a die-hard fan about the best scenes from Magic Mike XXL, they won't say the finale. They’ll say the gas station. Joe Manganiello’s character, Richie, is tasked with making a dour, exhausted convenience store clerk smile. He proceeds to do an improvised striptease to Backstreet Boys’ "I Want It That Way" while using a bag of Cheetos and a bottle of water as props.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

It’s hilarious. It’s also revolutionary for the genre.

Why? Because it shifted the focus from "look at my muscles" to "how can I make this person feel seen?" Director Gregory Jacobs took over for the sequel and leaned into the idea of "female pleasure" as a conversation rather than a performance. Richie isn't trying to look cool. He’s trying to be a goofball to brighten someone’s day. That specific scene went viral because it felt spontaneous, even though it was meticulously rehearsed.

The Technical Execution of the Dance Sequences

Soderbergh (who stayed on as cinematographer and editor for the sequels under his aliases Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard) shot the dance numbers with a wide lens. He didn't use the typical "Bourne Identity" shaky-cam or rapid-fire cuts that most dance movies use to hide poor footwork. He stayed back. He let the performers' bodies do the work.

- The Lighting: In the first film, the lighting is harsh. It highlights the tan lines and the stage makeup.

- The Sound Design: You hear the slap of skin on the stage. You hear the muffled roar of the crowd. It creates an immersive, almost claustrophobic feeling.

- The Framing: Often, the camera is positioned from the perspective of the audience, making the viewer feel like they are sitting in that humid Tampa club.

The furniture-making scene is another weirdly pivotal moment. Mike is in his garage, working on a table. No music. Just the sound of a saw. It’s one of the quietest scenes from Magic Mike, and yet it provides the stakes. Without that scene, the dancing is just vanity. With it, the dancing is survival. It’s a job.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Magic Mike’s Last Dance and the Shift to Art

By the time we got to the third installment, Magic Mike’s Last Dance, the vibe shifted toward "Magic Mike Live." The finale of that movie is a literal stage play in London. The water dance—where Tatum and ballerina Kylie Shea perform in a torrential downpour on stage—is arguably the most technically difficult of all scenes from Magic Mike.

It’s not stripping anymore. It’s contemporary dance.

The physics of that scene are wild. Dancing on a wet surface is a nightmare for grip. They had to use specialized flooring and the performers had to account for the weight of water-soaked denim. It’s a far cry from the thongs and tear-away pants of the first movie. It shows the evolution of the character from a hustler to a legitimate artist.

Cultural Impact and the "Male Gaze" Flip

Most movies are shot for the male gaze. These movies aren't. They are specifically framed to cater to what women—and the queer community—find appealing, which isn't always just raw muscles. It’s the eye contact. It’s the effort. When you watch the "B-Boy" style battles in the second film, the camera lingers on the joy of the performers.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The "mirror" dance with Stephen "tWitch" Boss (rest in peace to a legend) in XXL is a perfect example. It’s two men in perfect synchronization. The athleticism is undeniable. It’s basically a sports movie disguised as a dramedy about entertainers.

Real-World Takeaways for Fans and Creators

If you’re looking at scenes from Magic Mike for more than just entertainment, there are some genuine insights into performance and branding here:

- Authenticity Sells: Channing Tatum’s real-life experience informed the choreography. You can’t fake that level of comfort on stage. If you're creating content, lean into what you actually know.

- Physicality as Dialogue: In the first movie, Mike and the Kid (Alex Pettyfer) have an entire relationship dynamic built through how they move on stage together. Actions speak louder than the script.

- The Importance of "The Why": The best scenes aren't just about the "what" (the dance). They are about the "why" (paying bills, seeking validation, finding joy).

To truly understand the impact of this franchise, go back and watch the scenes where they aren't dancing. Watch the scene where Mike tries to buy a truck and gets rejected by the bank. Watch the scene where the guys are sitting around the campfire talking about their "post-stripping" dreams. That’s the engine that makes the flashy dance numbers work. Without the humanity, the spectacle is empty.

If you're revisiting the series, pay attention to the transition shots. Soderbergh loves a good "liminal space" shot—driving between gigs, the silence of the dressing room before the music starts. Those are the moments that ground the fantasy.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Watch the 2012 original specifically for the cinematography; it’s much more of an "indie" film than you remember.

- Compare the "Pony" scene in the first movie to the "Water Dance" in the third to see how the choreography moved from street-style to professional contemporary dance.

- Research the "Magic Mike Live" show in Las Vegas or London if you want to see how these cinematic techniques were translated into a 360-degree physical environment.

The series started as a story about a guy in Florida with a dream and ended as a global celebration of movement. Whether it's the humor of the gas station or the intensity of the final stage show, these scenes have left a permanent mark on pop culture history.