Everyone remembers that specific feeling of a flashlight beam hitting a grainy, charcoal illustration of a woman with a pale, melting face. It wasn't just a book. It was a rite of passage. If you grew up anywhere near a library in the last forty years, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz isn't just a title—it's a core memory. But why do these specific tales, mostly culled from old folklore and urban legends, continue to hold such a massive grip on our collective psyche? It’s not just the stories themselves, honestly. It’s the weird, visceral combination of Schwartz’s lean prose and Stephen Gammell’s haunting, nightmare-fuel artwork that created a perfect storm of childhood trauma and delight.

The books were essentially a gateway drug for horror fans. They didn’t treat kids like they were fragile. Instead, they leaned into the macabre, the unfair, and the downright gross.

The Folklore Roots of the Scariest Stories to Tell in the Dark

Most people don't realize that Alvin Schwartz wasn't just making this stuff up to be edgy. He was a serious researcher. He spent a massive amount of time in the Library of Congress and digging through the archives of the American Folklore Society. Basically, he was a folklorist who knew how to edit. He took these sprawling, sometimes clunky oral traditions and stripped them down to their barest, most effective bones.

Take "The Big Toe." It’s a classic "jump" story. The premise is absurd—a boy finds a toe in the ground and his family eats it in a stew—but the structure is ancient. It follows a traditional "return of the dead" motif found in European and Appalachian folklore. The power isn't in the logic; it's in the rhythm. Schwartz wrote these specifically to be read aloud, providing instructions on when to pause and when to scream. That’s why they work. They aren't meant for silent reading under a duvet, though that’s how most of us consumed them. They are scripts for social interaction.

"The Red Spot" is another one that ruined sleep for an entire generation. You know the one—a girl gets a spider bite on her cheek, it swells up, and then... well, you know. While it feels like a modern urban legend, versions of this story have been circulating since the Victorian era. It taps into a very primal, very real fear of infestation and the loss of bodily autonomy. It's the kind of story that sticks because it could happen, or at least your ten-year-old brain was convinced it could.

Why the Art Was More Than Just Decoration

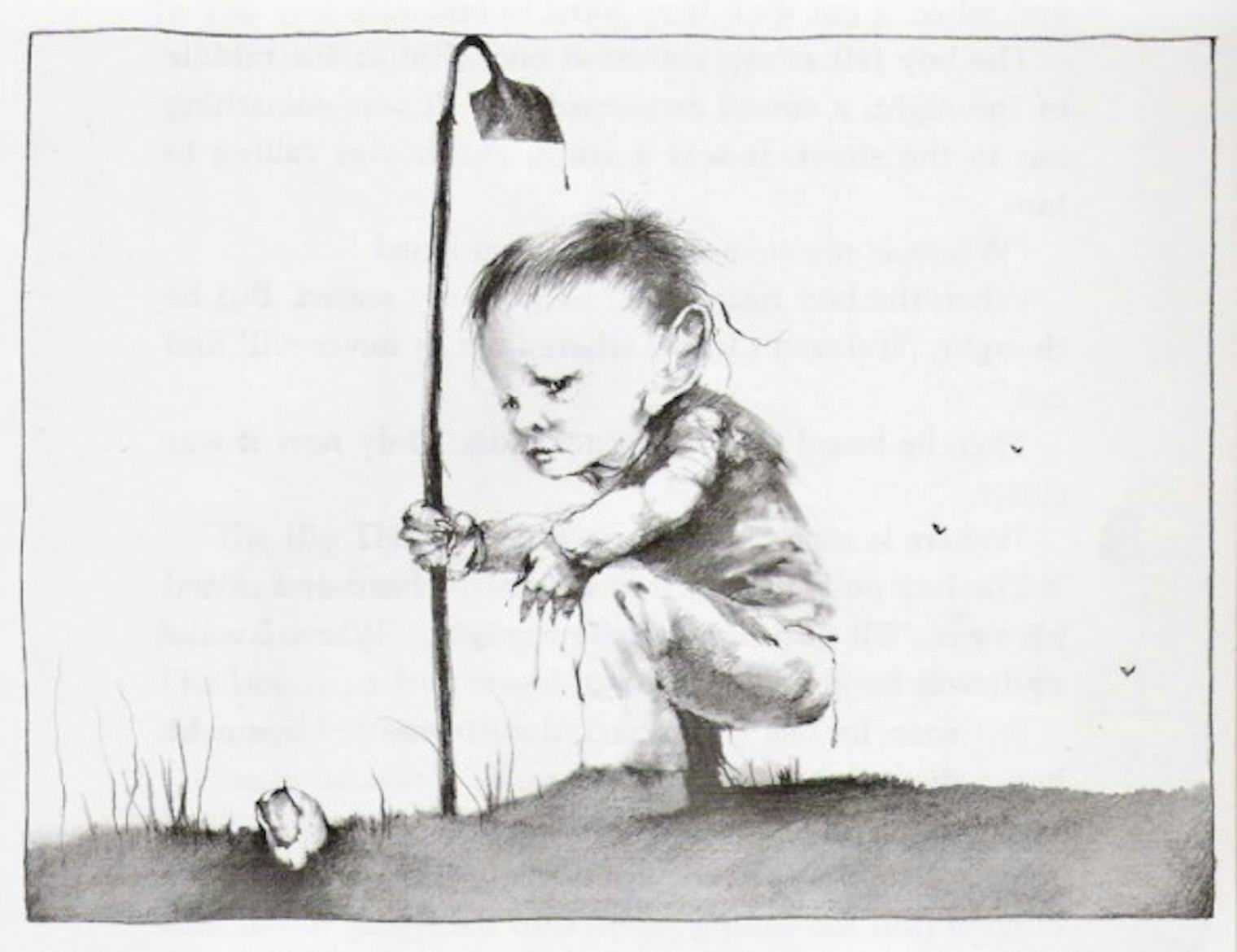

We have to talk about Stephen Gammell. Without Gammell, these books are just a collection of neat ghost stories. With him, they became legendary. His style—wispy, dripping, surreal charcoal drawings—captured a sense of rot and decay that felt almost illegal for a children's book.

In the story "The Haunted House," the illustration of the skeletal woman with the missing eyes and stringy hair didn't just illustrate the text. It transcended it. There was a huge controversy about this back in the 2010s. For the 30th anniversary, HarperCollins replaced Gammell’s art with illustrations by Brett Helquist. Helquist is a fantastic artist (he did A Series of Unfortunate Events), but the fans went absolutely ballistic. The new art was "too clean." It lacked the "ooze."

✨ Don't miss: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

People felt like their childhood was being sanitized. The backlash was so intense that the publisher eventually brought the Gammell versions back into print. It goes to show that for Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, the "scary" part wasn't just the plot. It was the atmosphere. It was the feeling that the book itself was haunted.

The Catcher in the Rye of Horror

These books are some of the most challenged and banned works in American library history. Throughout the 90s, the American Library Association (ALA) constantly had them at the top of their list of books people wanted removed from shelves. Parents were worried about "satanism" or just the sheer psychological toll of the imagery.

But here is the thing: kids love being scared in a safe environment. Dr. Margee Kerr, a sociologist who studies fear, often points out that "high-arousal" negative emotions like fear can actually trigger a sense of accomplishment and bonding once the "threat" is over. When you finish a story like "Harold"—the one about the sentient, murderous scarecrow—you feel like you survived something. You and your friends share that survival.

"Harold" is arguably the darkest story in the trilogy. Two farmers mistreat a scarecrow, and eventually, the scarecrow has enough. It doesn't just scare them; it literally skins one of them and stretches the skin out to dry on the roof. It’s bleak. It’s violent. And it’s a masterclass in building dread. The idea that an inanimate object is watching you, learning from your cruelty, is a trope that dates back centuries, but Schwartz localized it to a dusty, lonely pasture, making it feel painfully real.

Breaking Down the Most Iconic Tales

If we're looking at what actually makes the scariest stories to tell in the dark work, we have to look at the "Jump Story" vs. the "Dread Story."

- The Jump Story: These are the ones like "The Big Toe" or "The White Wolf." They rely on a sudden vocalization. The narrative is just a vehicle for a physical prank.

- The Dread Story: These stay with you. "The Thing" is a perfect example. Two boys see a sickly, rotting figure in the dark. It follows them. Years later, one of the boys sees that same figure in himself as he dies. That isn't a "boo" moment. That's an existential crisis wrapped in a campfire story.

Then you have "The Girl Who Stood on a Grave." It’s a classic cautionary tale about pride and bravado. A girl is dared to stick a knife into a grave to prove she isn't scared. She accidentally pins her own skirt to the ground, feels a "tug" (her own clothes), and dies of fright. It’s simple. It’s punchy. It’s a logic puzzle where the solution is death.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

The Urban Legends We Still Tell

A lot of what Schwartz included has migrated into the modern "creepypasta" world. "The Hook" and "The High Beams" are stories most people know without ever having read the books. They are part of the cultural fabric now.

"The High Beams" (the one about the truck driver following a woman and flashing his lights to stop a killer in her backseat) is a fascinating piece of folklore because it reflects societal anxieties about safety and the "predator in the shadows." It's less about ghosts and more about the very real dangers of being alone at night. Schwartz understood that horror needs a mix of the supernatural and the mundane to really get under your skin.

How to Tell These Stories Today

If you're looking to keep this tradition alive—maybe you're at a campsite or just trying to freak out your younger siblings—there’s an art to it. You can't just read the words.

- Pacing is everything. Schwartz actually left notes in the margins of the first edition. Slow down. Let the silence do the heavy lifting. If the story is about a creeping sound, make your voice a whisper.

- Don't over-explain. The reason "The Wendigo" is so terrifying is that we never really see the creature clearly. It's just a pair of feet running across the sky and a voice that sounds like the wind. Your audience's imagination is way more twisted than anything you can describe.

- The "Jump" needs to be earned. If you scream too early, you lose the tension. You have to wait until they are leaning in, trying to catch your every word. That’s when you hit them.

The Legacy of the 2019 Movie

When Guillermo del Toro and André Øvredal adapted the books into a film in 2019, they faced a massive challenge. How do you turn a collection of short, unrelated stories into a cohesive movie? They chose to make the book itself the villain.

The movie did something smart: it brought Gammell's drawings to life using practical effects. Seeing "The Pale Lady" walk down a red-lit hallway was a moment of pure catharsis for fans. It proved that the imagery wasn't just "scary for a kid"—it was fundamentally unsettling on a primal level. The film also touched on the era the books became popular, setting it in the late 1960s, a time of real-world horror and transition.

Actionable Steps for the Horror Enthusiast

If you want to dive back into this world or introduce it to someone else, don't just grab the first copy you see on Amazon.

💡 You might also like: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

First, find the original editions. You want the ones with the Stephen Gammell art. Look for used bookstores or specific "Original Art" reprints. The experience is fundamentally different without those messy, terrifying drawings.

Second, explore the sources. If you find a story you love, look at the "Notes" section in the back of the books. Schwartz was meticulous. He lists where the stories came from—whether it was a variant of a Brothers Grimm tale or a specific piece of regional American lore. It’s a great jumping-off point for anyone interested in the history of storytelling.

Third, try writing your own. Folklore isn't a dead thing. It’s constantly evolving. Think about the "urban legends" of today. Stories about deepfakes, "dead internet theory," or those weird, liminal spaces like the Backrooms are just the modern versions of what Schwartz was collecting forty years ago.

Lastly, understand that fear is a tool for empathy. When we tell the scariest stories to tell in the dark, we're sharing our vulnerabilities. We're acknowledging that the world is big, weird, and sometimes very cruel. But we're doing it together, around a fire or a flickering lamp, and that makes the dark a little less lonely.

To get the most out of your next spooky session, try pairing these readings with ambient soundscapes—think low-frequency drones or the sound of distant rain. It heightens the sensory deprivation and makes the "jump" moments significantly more effective. If you’re feeling particularly brave, read "The Dream" aloud in a room with a large mirror. Just don't blame me if you start seeing things in the corners of your eyes.