It starts with that unmistakable, rolling drum fill. Then the brass kicks in—bright, sharp, and smelling of buttered popcorn. If you grew up in the sixties, or even if you just have a thing for oldies radio, Saturday Night at the Movies by The Drifters is likely hard-coded into your DNA. It’s a song that feels like a physical place. It isn't just about cinema; it’s about the anticipation of the weekend.

Pop music usually tries to do too much. It tries to be a manifesto or a heartbreak cure. But this track? It just wants to tell you how good it feels to sit in the dark with a girl and a bag of candy. It’s simple. It’s brilliant. Honestly, it’s one of the few songs from 1964 that hasn't aged a day because the feeling of "getting away from it all" is universal.

The Magic of the 1964 Sessions

By the time The Drifters recorded this hit, the group was already a revolving door of talent. This wasn't the Ben E. King era anymore. We’re talking about the Johnny Moore years. Moore had this incredible, smooth-as-silk tenor that could carry a melody without ever sounding like he was trying too hard. He was the perfect vessel for songwriters Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil.

If those names sound familiar, they should. Mann and Weil were the heavy hitters of the Brill Building. They were the same duo behind "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'." They knew how to write for the teenage heart. When they sat down to pen Saturday Night at the Movies by The Drifters, they weren't trying to write high art. They were capturing a ritual.

The production by Bert Berns is what really seals the deal. Listen to the way the "shoo-do-wop" backing vocals bounce against the lead. It’s tight. It’s disciplined. But it still feels loose enough to dance to in a sweaty basement. There’s a specific kind of magic in those New York studio sessions where session musicians—who were often secret jazz geniuses—played three-minute pop songs for a paycheck and accidentally created immortality.

Why the Lyrics Still Hit Different

"Well, chewin' gum and crackin' peanuts..."

The opening lines are tactile. You can almost hear the floorboards crunching. Most people forget that in 1964, the "technicolor" mentioned in the song was still a relatively big deal for the average kid. The cinema was an escape from the gray reality of post-war life or the mundane grind of school and work.

💡 You might also like: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

The song captures a very specific social hierarchy. You aren't just going to see a movie; you’re going to sit in the "very last row." We all know what that means. It’s the universal code for teenage privacy. The Drifters managed to make a song about "necking" in the back of a theater sound wholesome enough for the Sunday morning radio while keeping that wink-and-a-nudge energy for the kids who actually bought the 45s.

It’s also interesting to note how the song avoids naming a specific film. It mentions "technicolor" and "stars up on the screen," but by keeping the movie generic, the song becomes timeless. It could be a Western. It could be a monster movie. It doesn't matter. The movie is just the background noise for the real event: being young and out on a Saturday.

The Drifters and the Art of Survival

A lot of folks don't realize how chaotic The Drifters' history actually was. The name was owned by a manager, George Treadwell, who essentially treated the singers like replaceable parts in a machine. Over 60 different vocalists have been "Drifters" over the decades.

By 1964, many critics thought the group was done. The British Invasion was hitting American shores like a tidal wave. The Beatles were everywhere. The Rolling Stones were making R&B look "old fashioned." Yet, Saturday Night at the Movies by The Drifters climbed all the way to number 18 on the Billboard Hot 100. In the UK, it was an even bigger smash, eventually hitting the top three during a re-release in the 70s.

Why did it survive the Beatles? Because it wasn't trying to be edgy. It was comfortable. It was the sound of the Atlantic Records hit machine firing on all cylinders. It proved that a well-crafted melody and a relatable hook could withstand even the most radical shifts in culture.

The Anatomy of a Hit: Breaking Down the Sound

If you strip away the vocals, the track is a masterclass in mid-sixties orchestration. You have:

📖 Related: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

- The driving, rhythmic bassline that keeps the "walking" tempo.

- The brass section that provides the "fanfare" feel of a movie opening.

- The handclaps that encourage listener participation (a classic Brill Building trope).

- That soaring, orchestral swell during the bridge that mimics a cinematic climax.

It’s a meta-song. The music sounds like the thing it’s describing. It’s "cinematic" pop.

When Moore sings about "the stars up on the screen," the music actually lifts. It’s an ascending progression that feels like looking up. This isn't accidental. The songwriters and arrangers of that era were obsessed with "word painting"—making the music reflect the literal meaning of the lyrics. It’s a lost art in much of today’s quantized, loop-based production.

Misconceptions About the Song

One thing people get wrong is thinking this was the group's "final" big moment. While it was their last Top 20 hit in the States during their prime, it actually kicked off a massive second life for them in Europe. The Drifters became a staple of the UK soul scene.

Another misconception? That it’s a "slow dance" song. While it has a romantic theme, the tempo is actually quite brisk. It’s a "stroll" or a "shag" dance favorite. If you go to any beach music festival in the Carolinas today, you will hear Saturday Night at the Movies by The Drifters within the first hour. It is the backbone of the "Carolina Shag" subculture, a testament to how Black vocal group music found a permanent home in the American South long after the charts moved on.

The Cultural Legacy

You’ve heard this song in a dozen commercials. You’ve heard it in movies about the sixties. It’s become shorthand for "innocence." But if you listen closely to the grit in the backing vocals, you realize it wasn't about innocence—it was about relief.

The sixties were heavy. Civil rights, the looming shadow of Vietnam, the Cold War. A three-minute song about peanuts and technicolor wasn't just fluff; it was a necessary breather. It’s why we still play it. Life is still heavy, and sometimes you just want to go to the movies.

👉 See also: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

The Drifters' version remains the gold standard, though it’s been covered by everyone from Dolly Parton to Robson & Jerome. Parton’s version is country-pop perfection, but it lacks that specific "street corner" soul that the 1964 original carries. There’s a certain weight to the original recording—a warmth from the analog tape—that digital covers just can’t replicate.

Practical Ways to Experience the Track Today

If you want to actually appreciate this song rather than just having it as background noise, you need to change how you listen to it.

First, find a mono mix if you can. The stereo spreads of the early sixties were often "fake" or awkwardly panned (vocals on one side, instruments on the other). The mono mix is punchy, centered, and hits you right in the chest.

Second, listen to it in the car at night. It’s a driving song. It was designed for AM radio through a single dashboard speaker. When those horns kick in while you’re moving through city lights, the whole thing clicks into place.

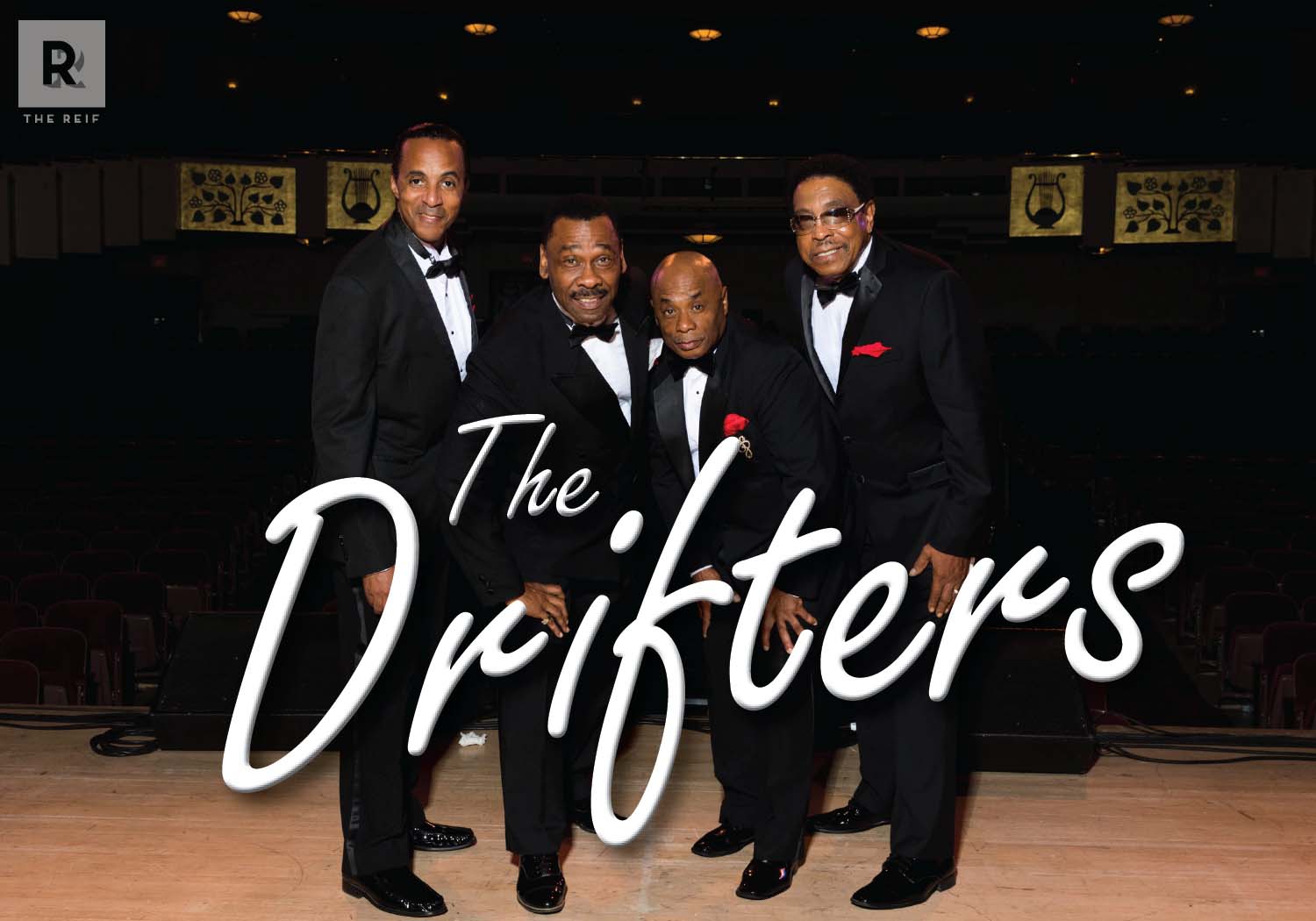

Finally, check out the live footage of the "definitive" lineup performing it. Seeing the choreography—the synchronized hand movements and the effortless cool of their suits—reminds you that The Drifters weren't just singers. They were entertainers in the truest sense of the word. They sold a dream of a perfect Saturday night, and sixty years later, we’re still buying it.

Your Next Steps for a Deep Dive

To truly understand the context of this era of music, you should look into the "Brill Building" sound. Start by looking up the discography of Mann and Weil. You’ll find that "Saturday Night at the Movies" is part of a larger tapestry of songs that defined the American teenage experience.

Go listen to "Under the Boardwalk" and "Up on the Roof" immediately following this track. You’ll notice a "trilogy" of sorts—the boardwalk, the roof, and the movies. These were the three "sanctuaries" for the characters in The Drifters' songs. Once you hear the thematic connection between these three hits, you’ll never hear them as individual singles again. They are chapters in a story about urban escape.

Check out the 1993 box set The Drifters: 1953–1958 and the subsequent volumes for the full sonic evolution. It’s the best way to hear how they transitioned from raw R&B into the polished, orchestral pop-soul that gave us the Saturday night anthem we still hum today.