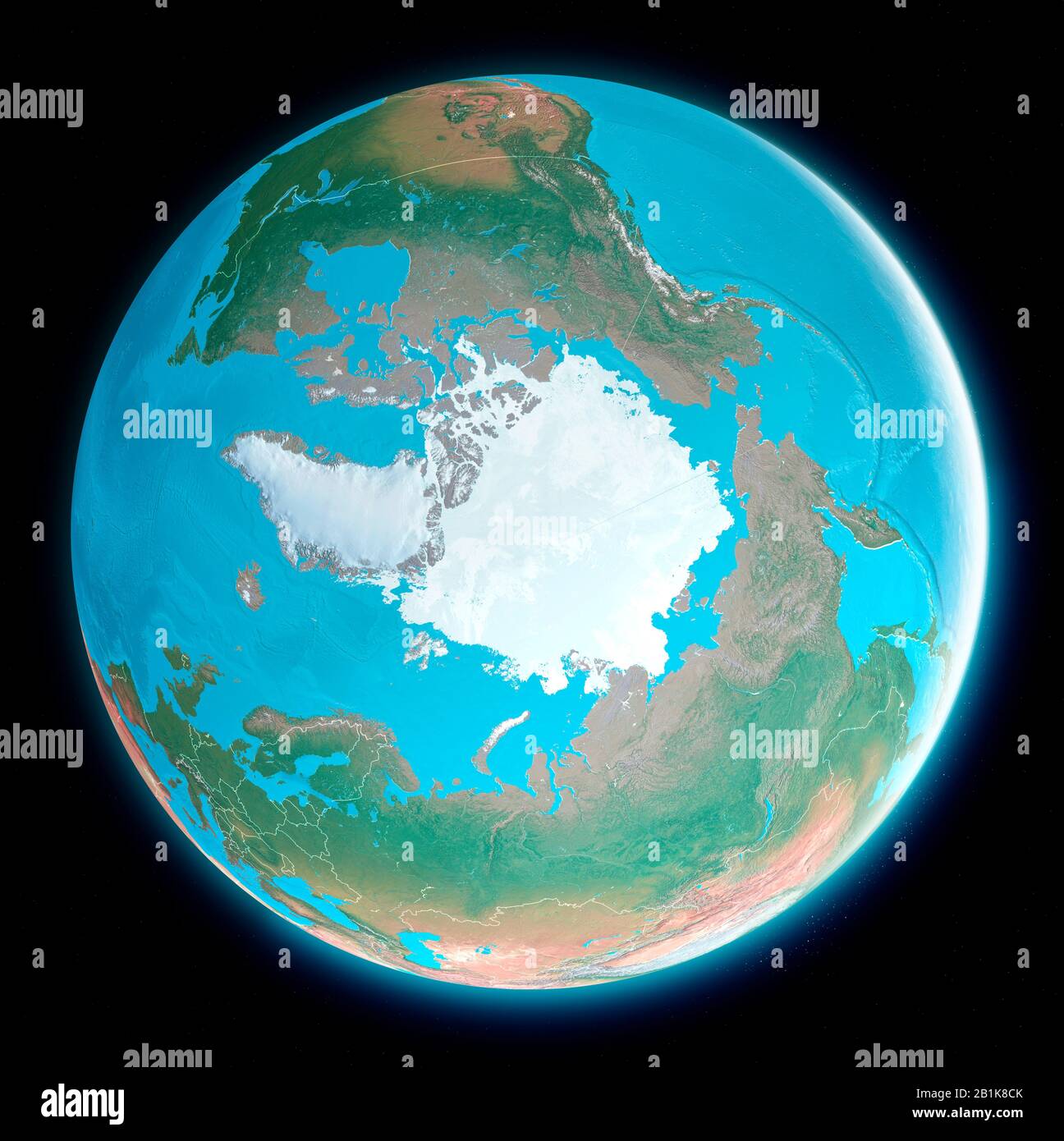

You’ve probably seen the "Blue Marble" photo from Apollo 17. It shows a majestic, ice-capped marble floating in the void. But if you try to find current, high-resolution satellite pictures of the north pole on Google Earth or a standard weather app, you might notice something weird. Sometimes there’s a giant black hole. Other times, the ice looks like a blurry, mismatched quilt of white squares.

It's not a conspiracy. Honestly, it's just physics and orbital mechanics being difficult.

The North Pole isn't a landmass like Antarctica. It’s a shifting, groaning mass of sea ice floating on the Arctic Ocean. Taking a picture of it from space is actually a logistical nightmare. Satellites don't just hover there; they fly in specific patterns, and most of them weren't designed to stare directly at the "top" of the world.

The "Black Hole" at the Top of the World

When people first started obsessing over satellite pictures of the north pole, they noticed a literal gap in the data. This led to some pretty wild internet theories about "Hollow Earth" entrances.

The reality is much more boring. Most imaging satellites, like the Landsat series operated by NASA and the USGS, fly in sun-synchronous orbits. They circle the Earth from pole to pole, but because of the way their sensors tilt and the physics of their path, they often miss the absolute geometric center of the North. Their orbits don't cross directly over 90 degrees north. It’s a "nadir gap."

Think of it like trying to take a panoramic photo of a room while standing in the middle of it; sometimes, the very spot you’re standing on doesn't show up in the stitch. NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites use an instrument called MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer), which has a wide enough "swath" to cover more ground, but even then, the resolution can get wonky at the extreme edges.

Why the Ice Looks Like a Messy Puzzle

If you zoom in on satellite pictures of the north pole, you’ll see jagged lines and color shifts. This happens because the Arctic is incredibly cloudy. Like, almost always.

👉 See also: When Were Clocks First Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Time

Optical satellites—the ones that take pictures using visible light, just like your phone camera—can't see through clouds. To get a clear view of the ice, scientists have to "stitch" together bits of clear images taken over several days or even weeks.

- One square might be from Tuesday.

- The square next to it might be from the following Friday.

- In that time, the ice has drifted miles.

This creates a "Frankenstein" image. The ice floes don't line up. The lighting changes because the sun is at a different angle. It’s not a single "snapshot" in time; it’s a temporal collage.

Radar: The Secret to Seeing Through the Dark

During the winter, the North Pole is plunged into months of total darkness. Visible light satellites are useless then. They just see blackness. To solve this, agencies like the European Space Agency (ESA) use "Synthetic Aperture Radar" (SAR) on satellites like Sentinel-1.

SAR doesn't need the sun. It bounces microwave pulses off the surface and measures what comes back. It can see through clouds, smoke, and total darkness. These aren't "pictures" in the traditional sense, but they are converted into grayscale images that show scientists exactly where the ice is thick, where it’s cracking, and where the "leads" (open water channels) are forming.

The Real Value of Sentinel and ICESat-2 Data

We aren't just taking these photos for desktop wallpapers. They are vital for survival.

NASA’s ICESat-2 (Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2) is a beast. It uses a laser altimeter—basically a super-powered laser pointer—that fires 10,000 pulses per second. It measures the time it takes for those photons to hit the ice and bounce back to the satellite. This allows us to measure the thickness of the ice, not just the surface area.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

Knowing the thickness is everything.

Dr. Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute, has often pointed out that surface area can be deceiving. A thin layer of ice might look the same as a thick one in a standard photo, but the thin stuff melts in a heartbeat. The ICESat-2 data gives us a 3D view of the Arctic that simple satellite pictures of the north pole never could.

How to Find "Real" Pictures Yourself

If you’re tired of the low-res stuff on standard map apps, you have to go to the source.

- NASA Worldview: This is arguably the coolest tool on the internet. You can look at daily satellite pulls from the last two decades. You can toggle between "True Color" and different infrared filters that make ice pop out in bright red or blue.

- ESA Sentinel Hub: This gives you access to the European fleet. It’s a bit more technical, but the resolution is staggering.

- NSIDC (National Snow and Ice Data Center): This is where the heavy-duty data lives. They provide daily updates on the "sea ice extent."

The Politics of the Lens

There’s a bit of a "space race" happening over these images, too. As the ice melts, new shipping lanes open up. The Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route are becoming gold mines for trade.

Russia, Canada, and the U.S. are all jockeying for better "situational awareness." This means more private satellites from companies like Planet and Maxar are being pointed North. They provide sub-meter resolution. You can literally see individual pressure ridges in the ice and the tracks of icebreaker ships.

What Most People Get Wrong About Arctic Imagery

A common misconception is that the North Pole is just a static white sheet. It isn't. It’s alive.

🔗 Read more: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

When you look at a time-lapse of satellite pictures of the north pole, it looks like a lava lamp. The ice is constantly rotating in a clockwise motion called the Beaufort Gyre. It’s being pushed by the Transpolar Drift Stream. If you stood at the North Pole with a flag, you wouldn't stay there. You’d wake up miles away the next morning.

Also, the "North Pole" in pictures isn't always the geographic north pole. Sometimes satellites are centered on the magnetic north pole, which is currently hauling tail toward Siberia at about 34 miles per year.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Arctic via Satellite

If you want to move beyond just looking at blurry maps and actually use this technology, here is how you do it:

- Monitor the Melt: Use NASA Worldview during the "melt season" (roughly March to September). Focus on the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas to see how the "marginal ice zone" breaks apart.

- Identify Lead Systems: Look for dark, spider-web-like cracks in the white ice. These are "leads." They are crucial for marine mammals like seals and whales that need to surface for air.

- Check the "Ice Age": Don't just look for white. Multi-year ice (ice that survived at least one summer) looks different—it’s typically thicker and rougher. Fresh "first-year ice" is smoother and darker in radar imagery.

- Follow the Ships: If you look near the coast of Russia or through the Bering Strait, you can often find the straight-line "scars" in the ice left by massive nuclear-powered icebreakers like the Arktika.

The Arctic is the most rapidly changing place on Earth. It’s our "canary in the coal mine." While the satellite pictures of the north pole might look like a glitchy mess sometimes, they are the most important records we have of a landscape that might look completely different in fifty years.

Next time you open a map app and see a weird blur at the top of the globe, remember: you’re looking at a composite of millions of laser pulses and radar echoes, trying to make sense of a world that refuses to stay still.