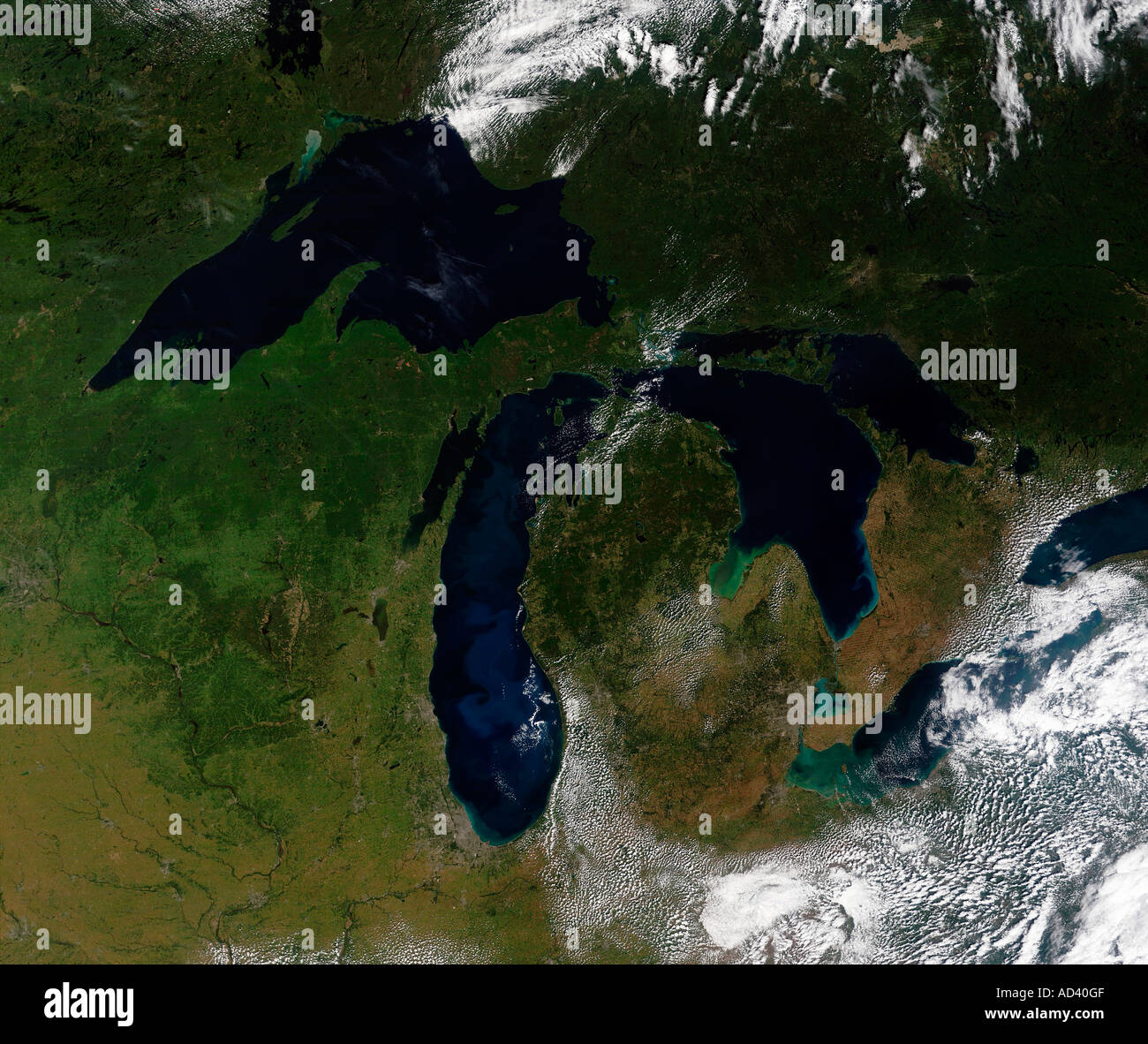

You’ve seen them. Those swirling, neon-turquoise patterns in Lake Michigan that look like a giant spilled a bottle of Gatorade into the water. Or the massive, jagged white sheets of ice that make Lake Superior look like the surface of Europa. People share these satellite pictures of the great lakes every time they go viral on social media, usually with a caption about how "breath-taking" nature is. But honestly? The prettiest photos usually show the lakes at their most stressed or chaotic.

What we see from 400 miles up isn't just a postcard. It's a massive data set. NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, equipped with the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) instrument, capture these bodies of water every day. They aren't just taking "pictures" in the way your iPhone does. They’re measuring light reflectance across different wavelengths to tell us if the water is healthy, if the fish are about to die from an algae bloom, or if a "whiting event" is turning the lake into a giant chemistry experiment.

The Science Behind Those Electric Blue Swirls

Let's talk about the turquoise. If you look at satellite pictures of the great lakes during late summer, specifically Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, you’ll see these incredible light-blue swirls. It’s not pollution. It’s not tropical sand. It’s actually calcium carbonate.

Scientists call these "whiting events." When the water warms up, the solubility of calcium carbonate decreases. This causes it to precipitate out of the water column as tiny, solid particles. These crystals scatter short-wave light—the blues and greens—giving the lakes that Caribbean look. It’s basically the lake’s way of "sweating" out excess minerals. It’s a complex dance of temperature, pH levels, and even the presence of invasive species like quagga mussels.

Speaking of mussels, they’ve fundamentally changed how the Great Lakes look from space. Back in the 80s, the lakes were much "murkier" in satellite imagery. Now, Lake Michigan is eerie and clear. Why? Because trillions of invasive mussels have filtered out almost all the phytoplankton. While clear water looks great in a photo, it’s actually a sign of a collapsing food web. The water is clear because it's empty.

When the Water Turns Toxic: The Green Menace

Not all colors are good. If you pull up a satellite view of Lake Erie in August or September, you’re likely to see a sickening, opaque green smear hugging the coastline near Toledo. This is the infamous Cyanobacteria bloom.

👉 See also: Why Doppler Radar Overland Park KS Data Isn't Always What You See on Your Phone

Unlike the harmless whiting events, these Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) are a massive problem. Satellite pictures of the great lakes are the primary tool used by the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) to track these blooms in real-time. By using specific spectral bands, they can distinguish between "good" algae and the toxic stuff that shut down the water supply for 400,000 people in Ohio back in 2014.

The satellites don't lie. You can literally trace the plume of nitrogen and phosphorus runoff coming from the Maumee River. It's a visual indictment of agricultural practices and urban runoff. You can see the green tendrils stretching out, pushed by the wind, sometimes covering the entire western basin. It’s gross. It’s dangerous. And without these high-altitude perspectives, we’d be flying blind trying to manage it.

The Great Lakes Ice Watch

Winter changes everything. Every January, the obsession shifts to ice cover. There’s a specific kind of beauty in a satellite shot of "pancake ice" or the massive cracks that form in the eastern end of Lake Erie.

But here’s the thing: ice is getting rarer.

If you look at the historical record of satellite pictures of the great lakes, the trend is clear and honestly a bit depressing. In 1979, the lakes hit a record 94.7% ice cover. These days, we’re seeing years where the lakes barely hit 10 or 15%. This matters because ice acts as a "lid." Without it, the water evaporates faster, leading to lower lake levels and massive "lake-effect" snowstorms in places like Buffalo and Syracuse.

✨ Don't miss: Why Browns Ferry Nuclear Station is Still the Workhorse of the South

When the ice is there, it’s a logistical nightmare for shipping. The U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards use RADARSAT-2 and Sentinel-1 data—which uses synthetic aperture radar (SAR) to see through clouds—to find leads in the ice for freighters. These aren't your standard "pretty" photos; they’re grainy, black-and-white maps that show the difference between "new ice" (thin and breakable) and "old ice" (thick and dangerous).

Sediment Plumes and the "Big Red" Look

After a major storm, the Great Lakes can look like they’re bleeding. This is particularly common in Lake Superior near the Duluth-Superior harbor or along the western shore of Lake Michigan.

The red-brown color comes from suspended sediment. In Lake Superior, it’s often the red clay from the shoreline being chewed up by massive waves. From space, these plumes look like smoke from a forest fire, drifting dozens of miles out into the deep blue water.

- Turbidity: It’s a measure of how "cloudy" the water is.

- Thermal Bars: In the spring, satellites show a sharp line where warm near-shore water meets the freezing deep water, trapping nutrients and sediment in a narrow band.

- Bathymetry: While satellites mostly see the surface, the clarity of the water now allows some sensors to "see" the lake floor in shallow areas like the Door Peninsula.

Why You Should Care About the Pixels

We live in a world where we take "Earth observation" for granted. We have GPS on our phones and Google Earth at our fingertips. But the constant monitoring of the Great Lakes is one of the most successful applications of satellite technology in history.

It’s about more than just a wallpaper for your desktop. It’s about predicting the next "dead zone" in Lake Erie. It’s about knowing if a cargo ship is going to get stuck in the ice. It’s about watching the slow, steady change of our climate in real-time.

🔗 Read more: Why Amazon Checkout Not Working Today Is Driving Everyone Crazy

Next time you see a satellite photo of the lakes, look closer. Don't just see the blue. Look for the sediment plumes near the river mouths. Look for the white specks of the massive 1,000-foot ore boats cutting a trail through the water. Look for the eerie clarity of Lake Michigan.

Actionable Insights for Tracking the Lakes

If you want to move beyond just looking at viral photos and actually track these changes yourself, there are professional tools available to the public for free.

First, check out the NOAA Great Lakes CoastWatch website. They provide near real-time satellite imagery, including sea surface temperature maps that are updated daily. It’s where the scientists go.

Second, use the NASA Worldview tool. It’s an incredible, browser-based interface that lets you scroll through decades of satellite imagery. You can compare "True Color" images from today to the same day ten years ago. It’s the best way to see how ice cover or algal blooms have shifted over time.

Finally, keep an eye on the GLOS (Great Lakes Observing System). They integrate satellite data with buoy data. If the satellite shows a massive plume of algae, the buoys will tell you exactly how much oxygen is left in the water beneath it.

The Great Lakes are changing faster than almost any other ecosystem on the planet. The view from space is the only way we can keep up. Stop looking at these photos as art and start looking at them as the biological and chemical status reports they actually are. Use the NASA Worldview tool to compare the current ice levels with the 2014 "Polar Vortex" year to see the staggering difference in how these lakes respond to temperature shifts. Check the Maumee River mouth every August if you want to see the reality of the Algal Bloom season before it hits the news cycle.