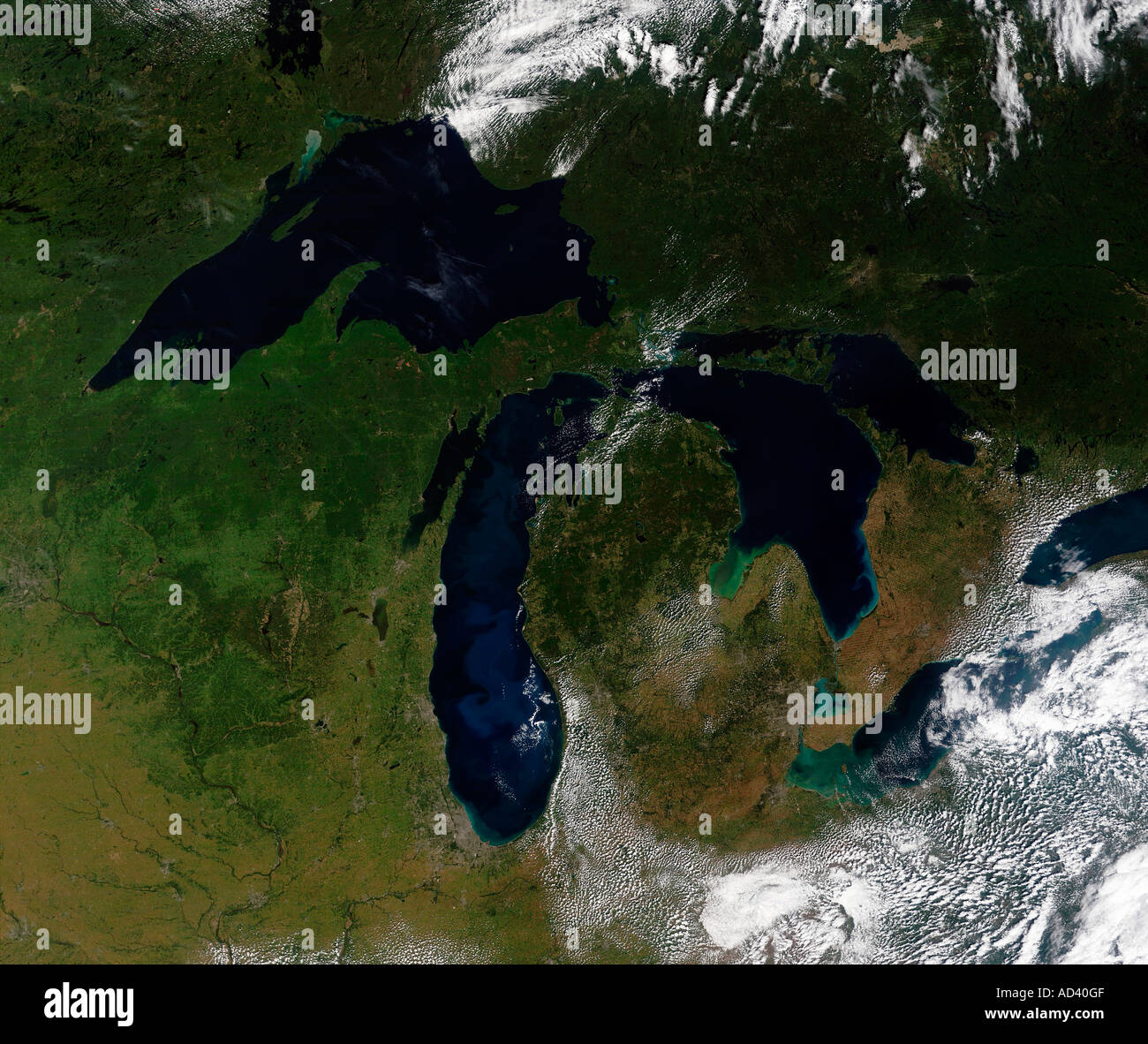

You’ve probably seen the viral shots on social media. Those swirling, turquoise ribbons in Lake Michigan that look more like the Caribbean than the Midwest. Or the terrifying, jagged white expanses of a frozen Lake Erie. Honestly, looking at satellite photos of the Great Lakes is addictive because these five massive bodies of water basically create their own weather, their own ecosystems, and their own visual masterpieces that change by the hour.

Most people think a satellite photo is just a "picture from space." It’s not. It’s data. When NASA’s Terra or Aqua satellites pass over, they aren't just snapping a JPEG; they are measuring light reflectance across different wavelengths. This is why you see those wild colors. Those neon greens and milky blues aren't Photoshopped—they are the result of "whiting events" or massive algae blooms that are visible from 400 miles up.

What Satellite Photos of the Great Lakes Actually Reveal

If you look at a shot of Lake Erie in late August, it’s often stained with a deep, sickly green. That’s the harmful algal blooms (HABs). It’s not just "pond scum." It’s a massive concentration of Microcystis cyanobacteria. NASA uses the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) instrument to track this. Scientists at NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) rely on these images to warn cities like Toledo about potential water intake issues.

Then you have the "whiting." This is my favorite part. In mid-to-late summer, Lake Michigan and Lake Ontario often turn a bright, opaque turquoise. This isn't algae. It’s actually calcium carbonate—basically liquid limestone—precipitating out of the water when the temperature rises. The water gets so warm that it can't hold the minerals anymore, and they crystallize. It’s a chemical reaction on a continental scale. Seeing it from space is the only way to appreciate the sheer volume of minerals moving around.

The Winter Chaos

Winter is when things get weird. Clouds usually block the view for weeks, but when a "clear sky" day happens, the imagery is breathtaking. You can see the "lake effect" snow bands forming. These are long, skinny rows of clouds that look like someone combed the atmosphere. They pick up moisture from the relatively warm water and dump it as feet of snow on places like Buffalo or Traverse City.

Ice cover is the big metric here. The Great Lakes Observation System uses satellite data to map exactly where the ice is moving. Because the lakes are so deep—Lake Superior holds 10% of the world's surface freshwater—they rarely freeze over completely. Seeing the black, deep water contrasted against the white, shifting ice floes provides a visual map of the lake’s currents that you’d never see from the shore.

Why the Resolution Matters

You might wonder why some satellite photos of the Great Lakes look blurry while others show individual piers. It comes down to the source.

NASA’s Landsat 8 and 9 are the workhorses. They give us a 30-meter resolution. That’s sharp enough to see large ships or the sediment plumes coming out of the Maumee River. But they only pass over every 16 days. If a storm hits on day three, they miss it.

That’s where the private sector comes in. Companies like Planet Labs have fleets of "CubeSats." They are about the size of a shoebox. They take lower-resolution photos but they do it every single day. For a coastal engineer trying to see how a beach in Grand Haven is eroding after a November gale, that daily frequency is way more important than a pretty, high-res shot from three weeks ago.

The "Ghost" Ships and Shipwrecks

Can you see shipwrecks in satellite photos? Sort of. Usually, no. The water is too deep and the light doesn't penetrate far enough. However, in the shallow sandy flats around the Manitou Islands or the Apostle Islands, sometimes—just sometimes—the sun hits the water at the perfect angle. You won't see the Edmund Fitzgerald (that's 500 feet down), but you might see the skeletal remains of 19th-century schooners in the shallows of Lake Huron's Thunder Bay.

The Sediment Secret

One thing that looks "dirty" in photos is actually just geology. After a big storm, the "muds" come out. Lake Superior’s south shore, near Duluth, often turns a vivid brick red. That’s not pollution. It’s the red clay and sandstone being churned up by the waves.

- Nearshore Shallows: These areas reflect more light and look lighter blue.

- Deep Basins: These look almost black because the water absorbs most of the light.

- Plumes: These are the brown "fingers" of water coming out of rivers after a rainstorm, carrying silt and nutrients into the main body of the lake.

It’s a constant battle between the clear, offshore water and the turbulent coastal zones. Satellite imagery is the only way we can monitor how fast these coastlines are disappearing. In 2020, when lake levels were at record highs, the photos showed massive chunks of bluffs falling into the water. It was a slow-motion disaster captured in pixels.

Practical Ways to Use This Information

If you’re a fisherman, a hiker, or just a nerd for Great Lakes geography, you don't have to wait for NASA to post a "Picture of the Day." You can go to the source.

Check the MODIS Today site. It’s run by the University of Wisconsin-Madison. They post "true color" imagery daily. If you want to see if the ice is off the bay in Door County before you head up, this is your best bet.

Use NOAA’s Great Lakes CoastWatch. This tool allows you to overlay surface temperatures onto the satellite photos. It’s wild to see a 20-degree difference between the shore and the middle of the lake.

Understand the "False Color" trick. Sometimes you'll see a photo where the trees are bright red and the water is neon blue. This is "Infrared" imagery. Scientists use it to tell the difference between healthy forest and stressed vegetation, or between ice and clouds, which can look identical in a standard photo.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Download the "Sentinel Hub" browser. It’s free and lets you look at European Space Agency data. You can zoom in on your own house or favorite beach.

- Track the "Bloom." Starting in July, watch the western basin of Lake Erie. If you see the green swirls moving toward the islands, you know the water quality is dropping.

- Monitor the Ice. In February, look for the "leads"—the cracks in the ice. They show you exactly where the wind is pushing the pack.

The Great Lakes are essentially inland seas. They are too big to understand from the ground. Only by looking at these satellite captures can you really see the "thermal bar" moving in the spring or the way the Niagara Escarpment shapes the flow of water into Lake Ontario. It’s a living, breathing system that looks best from a few hundred miles up.