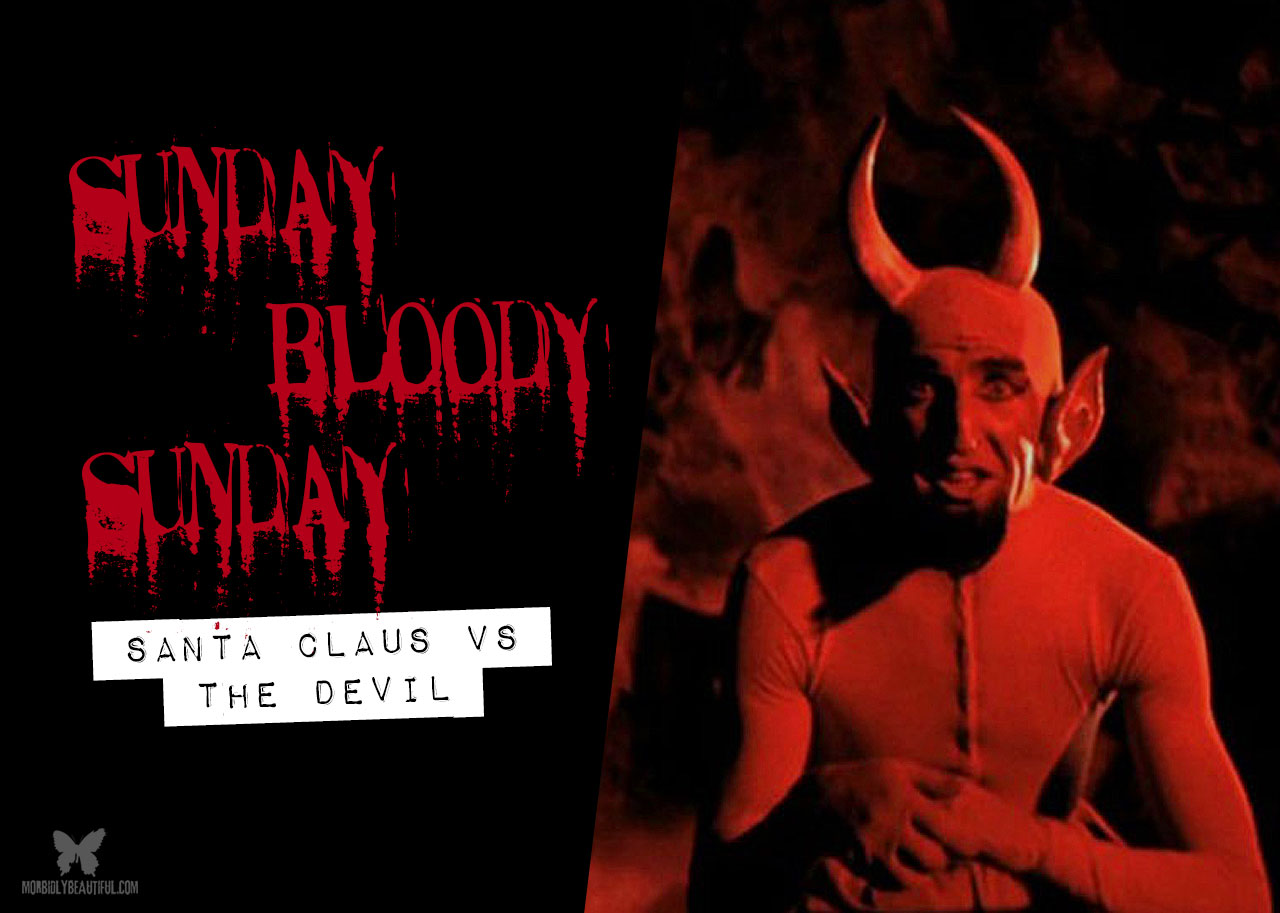

Ever looked at a vintage Christmas card and wondered why there’s a hairy, horned beast standing right next to a jolly old man in a red suit? It’s jarring. Honestly, if you grew up with the sanitized, Coca-Cola version of Christmas, the connection between Santa and the devil feels like a mistake. But it isn't.

History is messy.

The truth is that the modern image of Santa Claus didn't just drop out of the sky into a chimney. He’s a composite character, a "mutt" of folklore, hagiography, and—surprisingly—fears of the demonic. For centuries, the figure we now call Santa Claus didn't travel alone. He had "enforcers." In many Alpine and European traditions, the relationship between Santa and the devil (or devil-like figures) was a literal partnership. Saint Nicholas brought the hope; his dark companions brought the chains.

The Wild Origin of the "Bad Cop"

We have to go back. Way back. Before the mall Santas.

In the early Middle Ages, the figure of Saint Nicholas was strictly a religious one—a Greek Bishop known for his secret gift-giving. But as his legend moved into Germanic and Nordic territories, it collided head-on with pagan winter traditions. This is where things get weird. The wild hunt of Odin and the midwinter spirits didn't just vanish; they blended.

People needed a way to explain the duality of the season. Winter is dark. It’s cold. It’s scary. So, the folklore evolved to include a "helper" for the saint. This wasn't an elf. It was often a shackled version of the devil himself. The idea was simple: Saint Nicholas had conquered evil, and now he forced the devil to do his dirty work—specifically, the work of judging and punishing children.

You've probably heard of Krampus. He’s the most famous one. But he’s just one branch on a very gnarly tree. In different regions, you had Belsnickel, Knecht Ruprecht, or Hans Trapp. These characters were intentionally designed to look like the devil. They carried switches, they had long tongues, and they carried sacks—not for toys, but for kidnapping "bad" kids.

It wasn't just about being "naughty"

In the 1600s, this wasn't a joke. Parents used these stories as a genuine form of social control. If you didn't know your prayers or if you were disrespectful, the "devil" would beat you with a bundle of birch sticks. Saint Nicholas would stand there and watch. He was the "good" judge; the devil was the "bad" executioner. This weirdly symbiotic relationship between Santa and the devil figures helped maintain the moral order of the village during the long, dark nights of December.

Why the Church Actually Liked the Scary Stuff

You’d think the church would want to keep the devil far away from a saint. Nope.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

By tying a devilish figure to Saint Nicholas, the medieval church actually reinforced their own power. It showed that the "holy" could tame the "unholy." By having a chained Krampus or a subservient Knecht Ruprecht following Nicholas around, the imagery sent a clear message: God is in control of the dark things.

Historians like Maurice Bruce have pointed out that these horned figures likely have pre-Christian roots in the "Horned God" of the forest. When Christianity moved in, they didn't delete the character. They just rebranded him as a servant of the saint. It was a clever marketing move. It kept the locals happy because they got to keep their old winter rituals, but it kept the focus on Christian morality.

The Great American Scrubbing

So, where did the devil go? If Santa and the devil were such a tight-knit duo for a thousand years, why does modern Santa only hang out with reindeer?

The change happened mostly in the 19th century.

When the Dutch brought "Sinterklaas" to New York (New Amsterdam), he still had some of those rough edges. But New York elites in the 1820s, like Washington Irving and Clement Clarke Moore (who wrote A Visit from St. Nicholas), wanted to domesticate Christmas. They wanted it to be a family holiday, not a rowdy street festival involving drunken men dressed as demons.

They basically performed a "folklore lobotomy."

Moore took out the chains, the switches, and the demonic companions. He replaced the scary "helper" with eight tiny reindeer. He turned a tall, imposing bishop into a "right jolly old elf." Then, Thomas Nast, the famous political cartoonist, spent decades drawing this version for Harper's Weekly. By the time the 20th century rolled around, the devil had been completely edited out of the American Christmas script.

The Return of the Shadow

But you can’t keep a good monster down.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Lately, we’ve seen a massive resurgence in the dark side of Christmas. Krampusnacht festivals are popping up in places like Los Angeles, Austin, and Chicago. People are bored with the saccharine, corporate Santa. They want the grit back. There’s something deeply human about acknowledging the "shadow" side of the holidays.

Common Misconceptions About Santa and the Devil

People get a lot of this wrong. Let's clear some things up.

"Santa is an anagram for Satan." This is a huge one on the internet. It’s also totally wrong. "Santa" is the Spanish/Italian word for "Saint." The name Santa Claus comes from the Dutch "Sinterklaas," which is a contraction of Saint Nicholas (Sint Nicolaas). The linguistic similarity is purely coincidental.

"Krampus is the devil." Not exactly. In folklore, Krampus is a "beast" or a "demon," but in the specific context of the Saint Nicholas parade, he functions as a representation of the devil who has been tamed. He’s a subordinate.

"The red suit comes from the devil." Actually, Saint Nicholas was a bishop, and bishops often wore red robes. The red suit was solidified by illustrators like Nast and later by Haddon Sundblom for Coca-Cola, but it has zero "demonic" origin. It's just traditional ecclesiastical color.

The Psychology of the Duo

Why do we keep coming back to this?

Think about it. The holiday season is a period of extremes. We have the highest highs of "giving" and the lowest lows of winter depression and stress. The pairing of Santa and the devil represents that duality perfectly. One represents the reward; the other represents the consequence.

Modern parenting has "The Elf on the Shelf," which is basically a low-stakes, surveillance-state version of the medieval devil helper. The Elf watches you and reports back. The devil did the same thing, just with more rattling chains and a bit more fur. We haven't actually gotten rid of the "punisher" figure; we've just made him smaller and made of felt.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

What This Means for You This Christmas

Understanding the deep, dark roots of Christmas doesn't have to ruin the holiday. Honestly, it makes it more interesting. It gives the season a sense of history that goes beyond a 30-second TV commercial.

If you’re looking to explore this further, there are actual things you can do to experience this "lost" side of the holiday:

- Look into local Krampus Runs: Many cities now host "Krampuslaufs" in early December (usually around December 5th, Krampusnacht). It’s a great way to see the incredible craftsmanship of the masks.

- Research your own heritage: If you have German, Austrian, or French roots, look into the specific names of the "Santa helpers" from those regions. You’ll find stories of Le Père Fouettard (The Whipping Father) or Knecht Ruprecht.

- Re-examine the "Naughty or Nice" list: Next time you tell a kid that Santa is "watching," realize you’re participating in a tradition that used to involve a literal demon.

The story of Santa and the devil is a reminder that our traditions are never static. They are constantly being reshaped by culture, religion, and even the "boredom" of the public. Christmas was once a holiday about the tension between light and dark, heaven and hell, and rewards and punishments.

Modernity kept the presents and threw out the chains. But if you look closely at the old stories, the chains are still there, rattling just beneath the snow.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If you want to dive deeper into the historical intersection of folklore and the holiday season, start by reading The Battle for Christmas by Stephen Nissenbaum. It’s an academic look at how the holiday was transformed from a wild, sometimes violent street festival into the living room event it is today.

Also, check out the digital archives of the Museum of European Cultures. They have extensive collections of masks and historical depictions of the "dark companions" that prove this wasn't just some fringe belief—it was the standard for centuries.

Don't be afraid of the "dark" side of the holiday. Understanding the full history of Santa Claus makes the "joy" of the season feel a bit more hard-won and a lot more human. Sometimes, you need the shadow to see the light.

Actionable Insight: If you're hosting a holiday gathering and want a conversation starter that isn't just about the weather, bring up the "Enforcer" tradition. Most people are shocked to learn that "naughty" used to mean a trip in a burlap sack to the underworld, not just a lump of coal. It shifts the perspective of the holiday from consumerism back to its original, complex roots in folk justice and community survival.