Art isn't always about sunflowers and bright, smiling faces. Sometimes, the most honest thing you can do is put a pencil to paper and let out the heavy stuff. It's weird, right? We’re taught to chase happiness, but when you're actually feeling down, drawing a bouquet of daisies feels like a lie. If you’ve been looking for sad things to draw, you're probably not just looking for "dark art"—you’re likely looking for a way to process something that words can't quite catch.

Let’s be real. Melancholy has a specific texture.

It’s the way a wilted flower hangs its head or how a single, unmade bed looks in a room full of shadows. This isn't just about being "edgy." There’s actual psychological weight behind why we gravitate toward somber imagery. According to art therapists, externalizing a difficult emotion by drawing it makes that emotion feel smaller. It’s no longer living inside your chest; it’s just some graphite on a page.

The Science of Sketching the Sadness Away

You might think focusing on gloom would make you feel worse. Surprisingly, it’s often the opposite. Expressive arts therapy—a field championed by pioneers like Natalie Rogers—suggests that the act of "making" gives us a sense of agency over our pain. When you choose to depict sad things to draw, you are essentially taking the wheel. You’re the creator, not the victim of the feeling.

Think about the "widow’s peak" of a flickering candle or the jagged lines of a broken mirror. These aren't just objects. They’re metaphors.

Psychologists often refer to this as sublimation. It’s the process of transforming socially unacceptable or painful impulses into productive, creative outlets. Instead of ruminating, you’re observing. You’re looking at the curvature of a tear or the way a heavy coat slumps on a hanger. You’re turning a "bad" feeling into a "good" observation.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

Simple But Heavy: Sad Things to Draw When You’re Empty

Sometimes you don't want to draw a whole scene. You just want one thing. One image that sums up the "blah" feeling.

An Empty Swing Set.

There is something inherently lonely about a playground at dusk. One swing is slightly crooked. The chains are rusted. It suggests someone was just there, but now they’re gone. It’s a classic for a reason—it hits that nostalgia bone hard.

A Dead Houseplant.

We’ve all been there. You forgot to water it, or maybe you just didn't have the energy. Drawing a shriveled leaf is a great exercise in texture. The way the edges curl and turn brittle is a perfect metaphor for burnout. It’s not a tragedy; it’s just a slow, quiet fading.

A Cloud Raining Only on One Person.

It’s a bit of a trope, sure, but it’s a trope because it feels true. Focus on the contrast between the person’s soaked clothes and the dry ground just inches away. It captures that specific isolation where the whole world seems fine, but you’re stuck in a personal monsoon.

The Anatomy of Grief in Art

If you want to go deeper, look at how the masters handled it. Take Käthe Kollwitz. She was a German artist who dealt with incredible loss, and her work is a masterclass in sad things to draw. She didn't draw "pretty" sadness. She drew raw, visceral, "I-can't-breathe" sadness. Her lines were thick, dark, and often messy.

🔗 Read more: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

If you’re trying to capture grief, don't worry about being neat.

- Hands covering the face: This is one of the hardest things to draw, but also the most evocative. The way the fingers press into the skin tells you everything about the person's internal state.

- The Slump: Focus on the spine. A person who is sad doesn’t stand tall. Their shoulders roll forward. Their chin drops. The weight of the world is literal in art; it pulls the character toward the bottom of the frame.

- Negative Space: Sometimes the saddest part of a drawing is what isn’t there. A large, empty room with a tiny figure in the corner says more about loneliness than a thousand tears ever could.

Why We Lean Into the Dark Stuff

Honesty is a relief.

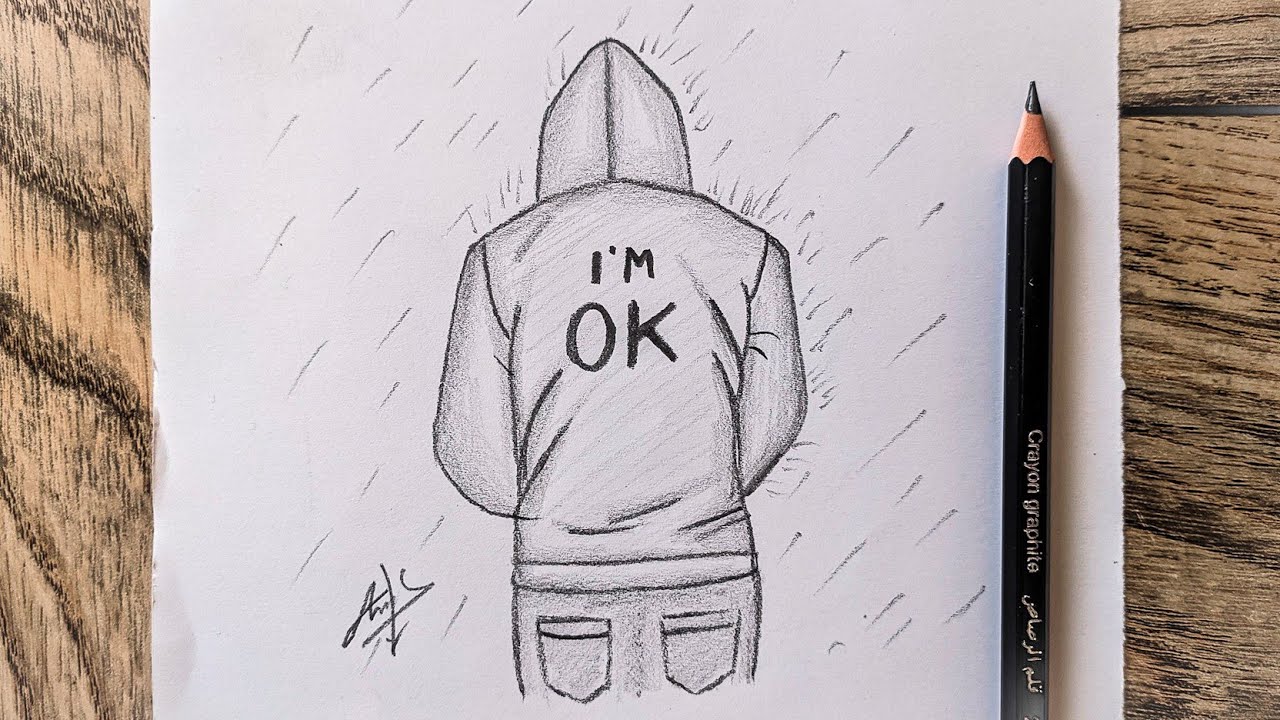

We spend so much time "performing" okay-ness. On social media, in the office, even with friends. Picking up a sketchbook to find sad things to draw is like finally taking off a pair of shoes that are two sizes too small. It’s a private space where you don’t have to pretend.

The "Sorrow" sketch by Vincent van Gogh is a perfect example. It's a drawing of a woman, disillusioned and worn down. Van Gogh himself was going through it at the time. He didn't try to make her look like a goddess; he made her look tired. There is a profound beauty in that kind of honesty. It tells the viewer—and the artist—that it is okay to be tired.

Practical Ideas to Get the Ink Flowing

Don't overthink it. Just grab a pen. A cheap ballpoint often works better for "sad" art because you can't erase it. You have to live with the mistakes, which is kind of the point.

💡 You might also like: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

- A bird with a broken wing trying to look at the sky. Focus on the eye of the bird. Make it look hopeful but stuck.

- A cracked porcelain doll. It’s a bit "horror-leaning," but it works for feeling fractured or "broken" on the inside while looking "perfect" on the outside.

- An old, rotary phone with the cord cut. This represents a loss of communication. It’s the feeling of having something to say but no one to say it to.

- A shadow that doesn't match the person casting it. Maybe the person is standing still, but the shadow is curled up in a ball. This is a powerful way to show internal vs. external reality.

- A lighthouse with a broken bulb. Total irony. The one thing meant to guide people is dark. It’s a heavy image for feeling lost or failing those who depend on you.

How to Lean Into the Technique

If you want the drawing to feel "sadder," play with your lighting. High-contrast lighting—what the Italians called Chiaroscuro—creates deep, swallowing shadows. Think about Rembrandt or Caravaggio. If half of your subject is disappearing into the darkness of the page, it creates a sense of mystery and melancholy.

Use "cool" colors if you're using more than just pencil. Blues, greys, and muted purples. Avoid high-saturation reds or yellows unless they serve as a sharp, painful contrast (like a single red balloon in a grey city).

Texture matters too.

Scratchy, frantic lines suggest anxiety and turmoil. Long, flowing, dragging lines suggest depression and lethargy. Your hand movement should mirror the emotion you're trying to pin down.

Moving Through the Sketch

The goal of looking for sad things to draw isn't to stay in the hole. It's to build a ladder out of it.

When you finish a drawing, look at it. Really look at it. You might find that the thing you were so afraid of—that big, scary emotion—looks a lot less intimidating when it's just a 4x6 sketch on a piece of paper.

Acknowledge the work. Then, if you want, turn the page.

Actionable Next Steps

- Start a "Shadow Journal": Dedicate one small sketchbook specifically for when you feel low. Don't show it to anyone. Use it only for these "sad" prompts. This removes the pressure to make "good" art.

- Practice "Blind Contour" Sadness: Try drawing a sad object without looking at your paper. The resulting distorted, messy lines often capture the feeling of grief or confusion far better than a "perfect" drawing.

- Focus on the Eyes: If you're drawing people, spend 20 minutes just drawing different types of "sad" eyes—red-rimmed, staring into space, or tightly shut. It’s the fastest way to build your emotional vocabulary in art.

- Change Your Medium: If you usually use a sharp pencil, try a charcoal stick or a fat marker. The lack of control can be incredibly cathartic when you're feeling overwhelmed.

- Set a Timer: Give yourself 10 minutes to "vomit" an emotion onto the page. Once the timer goes off, stop. This prevents you from spiraling and keeps the exercise as a form of release rather than rumination.