Kunta Kinte.

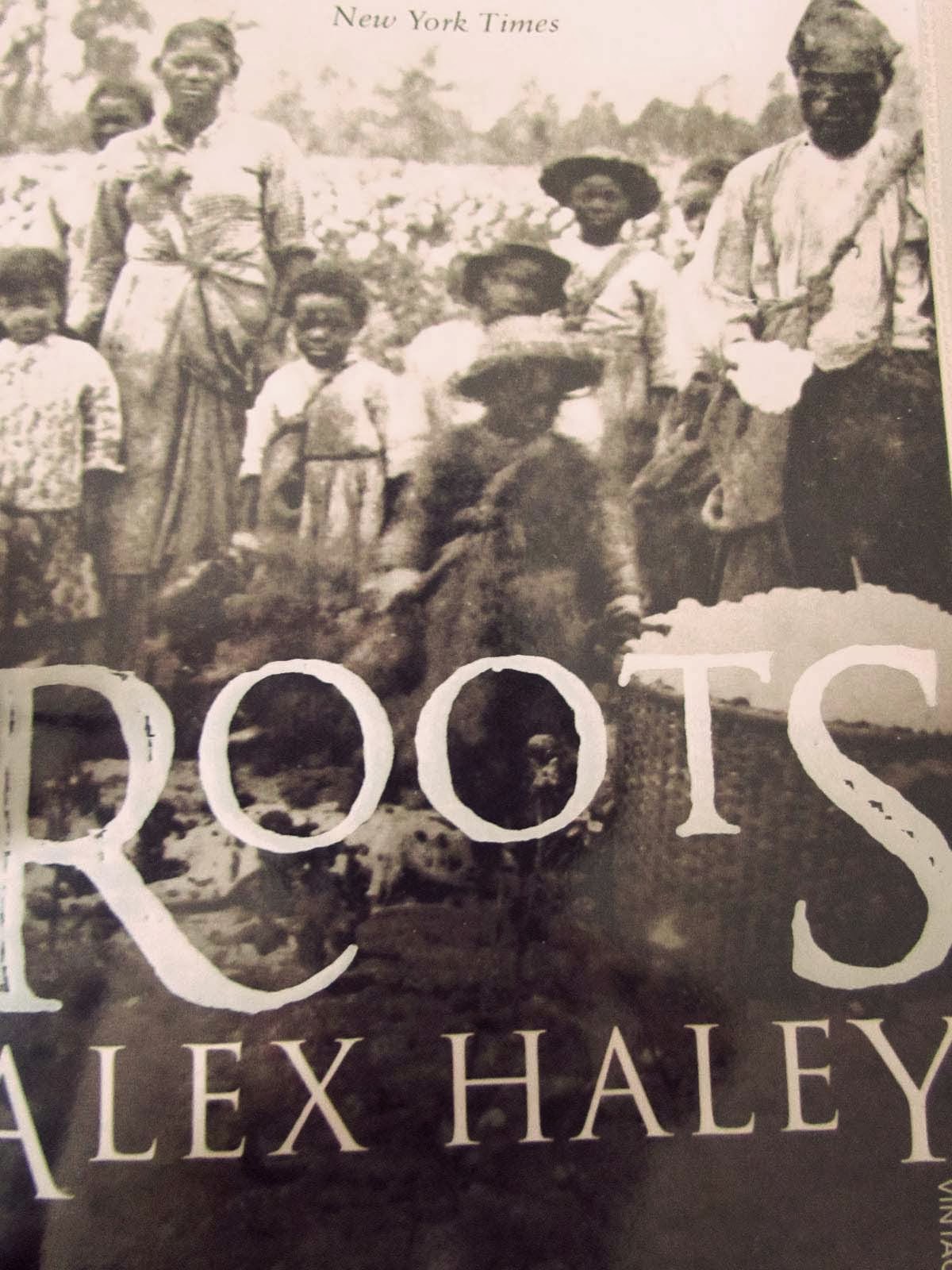

If you grew up in the seventies or eighties, that name isn't just a character. It's a cultural earthquake. When the Roots by Alex Haley book first hit shelves in 1976, nobody—not even the publishers at Doubleday—really knew what was about to happen. It wasn't just a bestseller. It became a permanent fixture of the American psyche, a sprawling, painful, and eventually triumphant 700-page epic that attempted to bridge the gap between a modern Black man and his West African ancestors.

It’s heavy stuff. Honestly, reading it today feels different than it did back then. We live in an era of DNA kits and ancestry websites, but in 1976, the idea of a Black American tracing their lineage back to a specific village in The Gambia was revolutionary. It changed the way we talk about identity. But it also sparked a firestorm of controversy regarding what is "fact" and what is "fiction."

The Gambian Connection: What Haley Actually Found

Alex Haley spent years in the National Archives. He lived in the basement of the Library of Congress. He was obsessed. The core of the Roots by Alex Haley book rests on a family story passed down through generations about an "African" who was kidnapped while looking for wood to make a drum.

Haley took these phonetic snippets—words like Kamby Bolongo and Kin-tay—and traveled to Juffure. There, he met a griot named Kebba Fofana. In African tradition, a griot is a living archive. Fofana told Haley the story of Kunta Kinte, a young man who disappeared from the village centuries ago.

It was a "eureka" moment that felt like destiny.

💡 You might also like: Why the tv show how i met your mother cast Still Defines Sitcom Chemistry

But here is where it gets complicated. Years later, journalists and historians like Philip Nourse and Donald Wright started poking holes in the narrative. They suggested the griot might have been "primed" to tell Haley what he wanted to hear. This doesn't make the book "fake," but it shifts it into a category Haley eventually called "faction"—a mix of rigorous fact and imagined emotional truth.

Why the Middle Passage Chapters Still Gut You

The book doesn’t blink. Most historical novels about slavery focus on the plantation, but Haley spends a massive chunk of the beginning on the Lord Ligonier, the slave ship.

The sensory details are overwhelming. You smell the rot. You feel the claustrophobia. Haley describes the "spoon-fashion" packing of human bodies in the hold so vividly it feels like a horror novel. It’s hard to read. You’ll want to put it down.

- The linguistic isolation: Kunta Kinte tries to speak to others, but they are from different tribes, different tongues.

- The psychological warfare: The crew uses the "great whip" to break spirits, not just bodies.

- The resistance: There is a failed mutiny that Haley describes with such frantic energy you forget the outcome is already written in history.

This part of the Roots by Alex Haley book is arguably its most important contribution to literature. It took the abstract "Middle Passage" from a history textbook and turned it into a visceral, terrifying reality.

The Plagiarism Scandal: The Shadow Over the Legacy

We have to talk about Harold Courlander.

Shortly after Roots became a global phenomenon, Courlander sued Haley, claiming that large portions of the book were lifted from his own novel, The African. It wasn't just a few coincidences. There were dozens of passages that were nearly identical.

Haley eventually settled for $650,000. He admitted that some material from Courlander's work had somehow ended up in his notes.

Does this ruin the book? For some, yes. For others, it’s a footnote to a larger cultural truth. The controversy is why many academics treat the Roots by Alex Haley book as a cultural artifact rather than a strictly historical record. It's a masterpiece of storytelling that tripped over its own ambition.

The 1977 Miniseries: When America Stopped Moving

You can't separate the book from the TV event. For eight consecutive nights in January 1977, 130 million people tuned in. It’s almost impossible to imagine that kind of monoculture today.

People weren't just watching TV; they were having a collective national therapy session. LeVar Burton became the face of Kunta Kinte, and suddenly, the "invisible" history of the Black experience was in every living room in America. It forced white audiences to confront the brutality of their own history, and it gave Black audiences a sense of rootedness that had been systematically stripped away by the institution of slavery.

The "Faction" Debate: Is it History or Myth?

If you go to a library, you might find Roots in the non-fiction section. Or you might find it in fiction. Even the Pulitzer Prize committee struggled with this, eventually giving Haley a "special award" rather than a standard category prize.

Genealogists have pointed out that the census records Haley used don't always align with the timeline of Toby (Kunta Kinte's slave name). For example, the real "Toby" may have been in America years before the Lord Ligonier ever docked.

Does it matter?

In the 1970s, the Roots by Alex Haley book gave millions of people a blueprint for how to look for themselves. It didn't matter if every birth date was exact; the emotional accuracy of the struggle was what resonated. Haley wasn't just writing a biography; he was writing a foundational myth for a people whose history had been intentionally erased.

The Characters You Never Forget

- Kunta Kinte: The defiant soul who refuses to accept his name is Toby. His foot is amputated for trying to run. He is the anchor.

- Fiddler: The complicated mentor. He’s a "house slave" who has found a way to survive by playing music, representing the tragic compromises of the era.

- Kizzy: Kunta’s daughter, who carries the secret of her father's origin even after she is sold away from him.

- Chicken George: The flamboyant, charismatic grandson who uses his skills as a gamecock trainer to try and buy his family's freedom.

These aren't just names. They represent the evolution of the Black American identity from "African" to "Enslaved" to "Survivor."

How to Approach the Book Today

If you're picking up the Roots by Alex Haley book for the first time, don't treat it like a dry textbook. Read it as a saga.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch WWE Saturday Night Main Event and Why the Reboot Actually Matters

It’s a story about the resilience of the human spirit. It’s about how a single name—Kinte—can travel through two hundred years of blood and toil to land in the ear of a small boy in Tennessee.

The prose is straightforward. It’s not "flowery" or overly literary. Haley was a journalist by trade, and he writes with a reporter's eye for detail, even when he's imagining the conversations between the characters.

Actionable Steps for Readers and Researchers

- Read the Courlander comparison: If you're interested in the ethics of writing, look up the side-by-side passages between Roots and The African. It’s a fascinating lesson in how "inspiration" can cross the line.

- Check the Bibliographies: Look for the work of Gary B. and Elizabeth Shown Mills. They are professional genealogists who did a deep dive into Haley's sources. Their work provides a necessary counter-perspective to the book’s claims.

- Watch the 2016 Remake: While the 1977 version is iconic, the 2016 miniseries incorporates more modern historical research and a slightly different tone that reflects our current understanding of West African culture.

- Start Your Own Search: Use the book as inspiration to look into your own family. Tools like FamilySearch or the National Archives are much easier to navigate now than they were in Haley's day.

- Visit the Alex Haley House Museum: If you're ever in Henning, Tennessee, see where the stories were first told on that porch. It puts the scale of the book into a tangible, human perspective.

The Roots by Alex Haley book remains a cornerstone of American literature. It’s flawed, it’s controversial, and it’s deeply moving. It proved that history isn't just a list of dates; it's a living, breathing thing that lives inside our DNA. Whether Kunta Kinte was exactly who Haley said he was is almost secondary to the fact that millions of people finally felt seen because of his story.