You’ve probably seen the memes. Or maybe you played a video game where a guy with a massive beard swings a green dragon blade and wipes out a thousand soldiers in a single swoop. That’s Guan Yu. He’s a god now. Literally. People in Hong Kong and Taiwan have shrines to him in their shops. But before he was a deity, he was just a character—or a real person, depending on who you ask—in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

It’s a 14th-century novel. It’s also a historical record. Sorta.

The lines between what actually happened in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD and what the author, Luo Guanzhong, decided to spice up are incredibly blurry. That’s the magic of it. We’re talking about a period of Chinese history where the Han Dynasty collapsed and three rival states—Wei, Shu, and Wu—spent decades trying to out-murder and out-smart each other to unify the country. It’s messy. It’s violent. Honestly, it makes Game of Thrones look like a playground dispute.

Most people today encounter this story through the Dynasty Warriors games or Total War: Three Kingdoms. But if you only know the games, you’re missing the sheer psychological depth of the source material. It isn't just about big battles. It’s about the "Mandate of Heaven" and the soul-crushing weight of loyalty in a world that’s falling apart.

The Big Lie: 70% Fact, 30% Fiction

Scholars usually cite a specific ratio for the Romance of the Three Kingdoms: "seven parts fact, three parts fiction." This isn't a hard rule, but it helps explain why people still argue about it today.

Take the "Empty Fort Strategy." In the book, the brilliant strategist Zhuge Liang is trapped in a city with no army. A massive enemy force led by Sima Yi arrives. What does Zhuge Liang do? He opens the gates, sits on the wall, and plays a lute. Sima Yi thinks it’s a trap and retreats. It’s an iconic scene. It’s also probably total nonsense. There is no historical evidence in the Sanguozhi (the actual historical records) that this specific event happened to Zhuge Liang. But we believe it because it fits his "vibe."

History is written by the winners, but legends are written by the fans.

Luo Guanzhong was writing during the Ming Dynasty, over a thousand years after the events took place. He had a bias. He wanted the Shu Han kingdom—led by the "benevolent" Liu Bei—to be the heroes. Because of this, the "villain," Cao Cao, got a bit of a raw deal in the public imagination.

In the novel, Cao Cao is a cruel, scheming usurper. In reality? He was a brilliant poet and a visionary leader who actually cared about agricultural reform and meritocracy. He was the one who famously said, "I would rather betray the world than let the world betray me." That line defines his character in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, portraying him as the ultimate pragmatist. Whether he actually said those exact words is up for debate, but the sentiment stuck.

The Peach Garden Oath: Bromance or Duty?

The story kicks off with three guys meeting in a backyard filled with peach blossoms. Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei. They swear to be brothers. They promise to die on the same day.

It’s the ultimate "ride or die" moment.

But look closer at the politics. Liu Bei was a guy selling straw sandals who claimed to be descended from royalty. He needed muscle. Guan Yu and Zhang Fei were that muscle. While the novel paints this as pure, unadulterated brotherhood, historians like Rafe de Crespigny—probably the western world's leading expert on this era—point out that these alliances were often born of extreme necessity during the Yellow Turban Rebellion. The social order had vanished. If you didn't have a "brother" to watch your back, you were dead.

Why the Strategy Matters More Than the Swords

If you pick up a copy of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, you’ll notice something quickly. The battles are won in the tent, not on the field.

💡 You might also like: You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth: Why Meat Loaf’s Best Duet Almost Didn't Happen

Strategy is the real protagonist here.

The Battle of Red Cliffs is the turning point. It’s the moment where the underdog alliance of Liu Bei and Sun Quan managed to burn Cao Cao’s massive fleet to a crisp. How? By chaining the ships together (Cao Cao’s idea to prevent seasickness) and then sending in fire ships.

But the novel adds layers of supernatural flair. Zhuge Liang supposedly "summoned" the southeastern wind to blow the fire toward the enemy. Historically? They probably just waited for the weather to change. But "waiting for the weather" doesn't make for a legendary epic.

This emphasis on "stratagem" influenced Chinese military thought for centuries. It’s why the Thirty-Six Stratagems are so often linked to this period. People don't just read this for the story; they read it for the lessons in leadership and deception.

- The Chain Stratagem: Making your enemy link their resources so one blow takes them all down.

- Borrowing Arrows with Straw Boats: Zhuge Liang sent boats filled with straw dummies into the fog; the enemy shot thousands of arrows at them, which he then collected and used. Pure genius.

- The Beauty Trap: Using a woman (Diaochan) to sow discord between a tyrant (Dong Zhuo) and his bodyguard (Lu Bu).

The Tragedy of Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang is the most famous figure in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. He’s the guy who knows everything. He can predict the future. He’s basically a wizard.

But his story is a tragedy.

He spent the last years of his life launching "Northern Expeditions" to try and reclaim the north for Liu Bei’s son. He failed every single time. He died of exhaustion in a military camp, knowing his dream of a unified China under the "rightful" heirs was dead.

There’s a deep melancholy in the later chapters of the book. The heroes you spent 800 pages loving start dying off. Not in glorious battles, but from old age, illness, or stupid mistakes. Guan Yu gets captured and executed because he was too proud. Zhang Fei gets murdered in his sleep by his own men because he was a mean drunk. It’s brutal.

The Cultural Footprint: From Temples to TikTok

You can’t escape the Romance of the Three Kingdoms in East Asia. It’s in the DNA.

Business schools in Japan use it to teach management. In Korea, there’s a saying that you shouldn’t trust a man who hasn’t read the Three Kingdoms at least three times—but you should also never trust a man who has read it too many times (because he’ll be too good at scheming).

And then there’s the gaming world.

Koei Tecmo has been milking this IP since the 1980s. Dynasty Warriors turned these historical figures into superheroes. While purists might hate it, these games kept the story alive for a new generation. You might start by "button mashing" as Zhao Yun, but eventually, you find yourself on Wikipedia at 3:00 AM wondering if he actually rescued Liu Bei’s infant son at the Battle of Changban. (He did, according to the records, though he probably didn't kill 5,000 guys while doing it).

The impact is everywhere.

- Language: Countless Chinese idioms (chengyu) come directly from the book. "Say Cao Cao and Cao Cao appears" is the Chinese version of "Speak of the devil."

- Religion: Guan Yu is worshipped as a god of war, wealth, and literature.

- Film: John Woo’s Red Cliff is one of the most expensive Asian productions ever made.

How to Actually Read This Thing

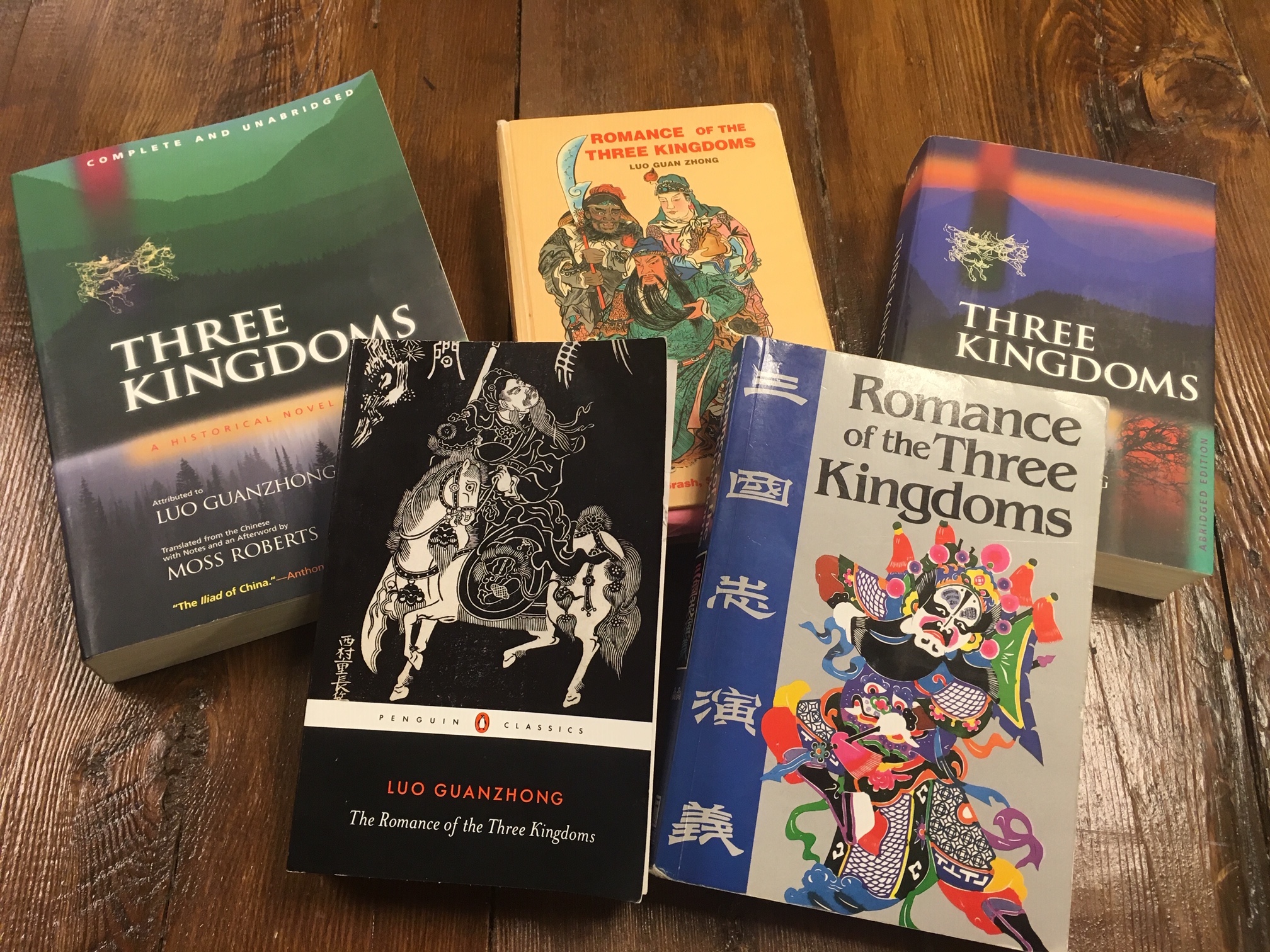

If you want to dive into the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, don’t just grab the first copy you see. It’s a beast.

👉 See also: Where to Stream Final Destination Movies Right Now Without Getting Tricked

The Moss Roberts translation is generally considered the gold standard for English readers. It captures the "vibe" without being too dry.

You have to realize that the first few chapters are a whirlwind of names. You will get confused. You will forget who is fighting for whom. That’s okay. Stick with it until the coalition against Dong Zhuo begins. That’s when the drama really hits its stride.

Don't expect a modern novel. There isn't much "inner monologue." Characters are defined by their actions and their speeches. It’s more like an epic poem or a grand stage play.

Also, ignore the "benevolence" of Liu Bei for a second. Read between the lines. He’s a politician. Every time he cries in the book—and he cries a lot—he usually gets something out of it. It’s a fascinating look at how "virtue" can be used as a political weapon.

Common Misconceptions

- Lu Bu was the strongest: In the novel and games, yes. In history, he was a talented cavalry commander but a bit of a flake. He betrayed everyone he ever worked for. He wasn't some noble warrior; he was a liability.

- The Three Kingdoms were equal: Not even close. Cao Cao’s state of Wei had the most land, the most people, and the best economy. The "Three Kingdoms" period was mostly a long, slow grind where Wei eventually won (well, the Sima family who took over Wei won).

- It’s just for guys: Surprisingly, no. The female characters like Lady Sun (a badass archer who married Liu Bei) and the Qiao sisters have massive fanbases and their own complex subplots in various adaptations.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're looking to understand why this matters now, or how to get into it without losing your mind, follow these steps:

- Start with a Summary: Watch a YouTube documentary or read a brief outline of the Han Dynasty's fall. Knowing the "end" doesn't spoil it; it makes the journey more interesting.

- Focus on the "Three Sovereigns": Instead of trying to learn 1,000 names, focus on the leaders: Cao Cao, Liu Bei, and Sun Quan. Everyone else is an extension of their wills.

- Watch the 2010 TV Series: It’s available on various streaming platforms with subtitles. It’s long, but it does a great job of showing the political "chess game" that the books describe.

- Check the Maps: Keep a map of 2nd-century China open. Understanding the geography explains why certain battles (like the Hanzhong campaign) were such a big deal.

- Apply the Logic: Next time you’re in a "negotiation" or a difficult work situation, ask yourself: "Am I being a Cao Cao (the pragmatist) or a Liu Bei (the idealist)?" It’s a fun psychological exercise.

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms isn't just a book. It’s a blueprint for how people behave when the world is ending. It shows that even in the middle of total chaos, people still care about honor, even if they have to lie, cheat, and steal to keep it.

Go find a copy. Or a game. Or a movie. Just don't expect a simple story about good versus evil. It’s way more complicated—and way more interesting—than that.