Art can be a headache. Sometimes it’s literally illegal. When you walk up to Canyon by Robert Rauschenberg at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, you aren't just looking at a painting. You're looking at a taxidermied bald eagle that once sparked a massive standoff with the United States government.

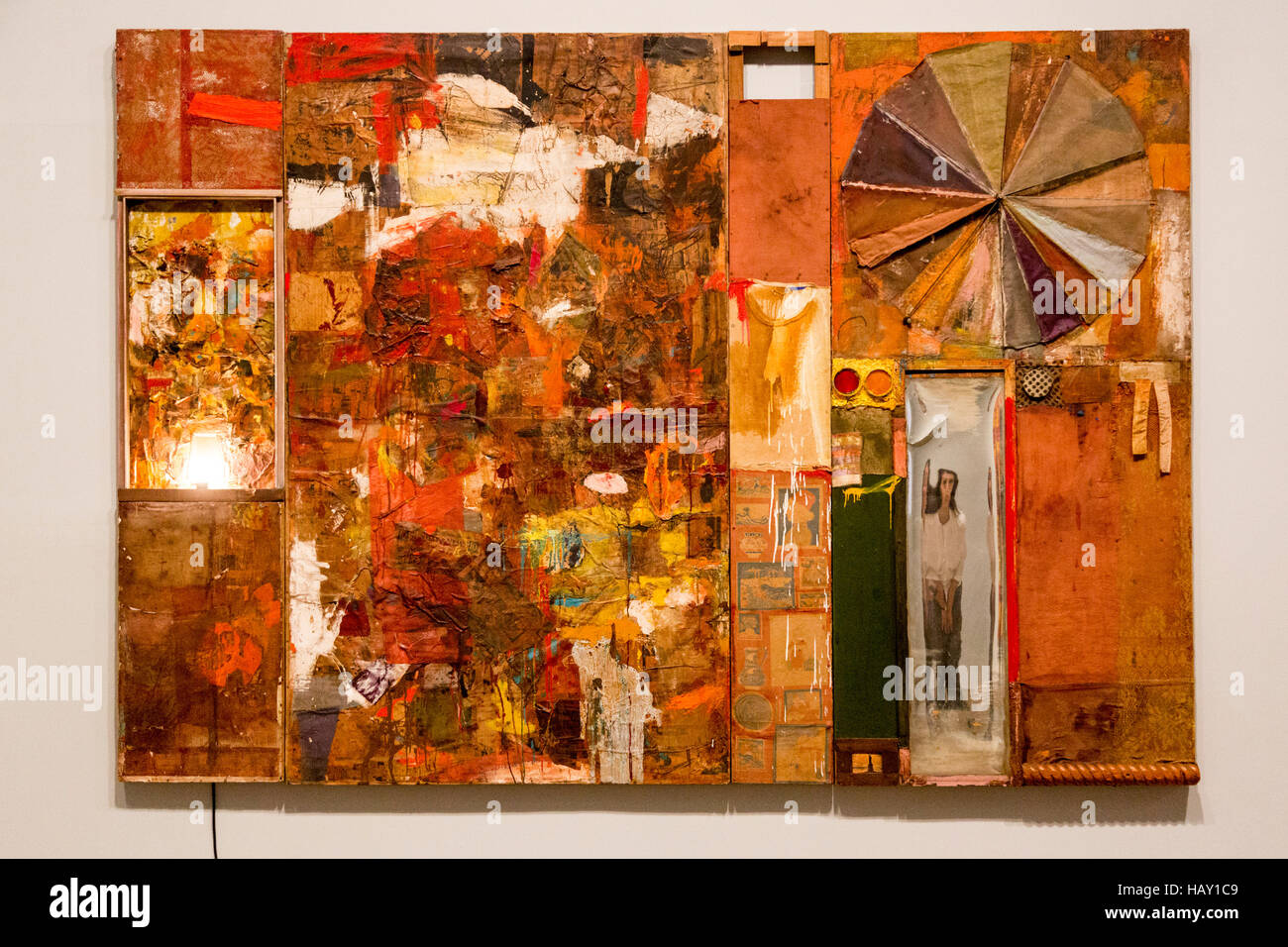

It’s big. It’s messy. It’s a "Combine," a term Rauschenberg coined to describe his frantic, brilliant habit of shoving the real world onto a canvas. He didn't want to just paint a picture of life; he wanted to use the physical junk of life itself. A pillow hangs from the bottom by a string. There’s a mirror, some metal, and some old photographs. And then, of course, there is that bird.

The Eagle in the Room

The story of Canyon by Robert Rauschenberg is basically a legal thriller disguised as art history. For decades, the piece belonged to the legendary dealer Ileana Sonnabend. When she passed away in 2007, her heirs hit a wall. Because the work features a stuffed bald eagle—a bird protected under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act—it is technically illegal to sell it.

The IRS didn't care.

They looked at the masterpiece and said it was worth $65 million. They demanded $29 million in estate taxes. The family was stuck in a nightmare: they couldn't sell the art to pay the tax because selling it would be a federal crime, but the government insisted they pay taxes on its "market value" anyway. Eventually, after a lot of legal posturing, the family donated it to MoMA, and the IRS dropped the claim. It’s one of those rare moments where the physical reality of the materials used in a piece of art dictated the financial fate of a multi-million dollar estate.

✨ Don't miss: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

What Are You Actually Looking At?

Let’s break down the chaos. Canyon by Robert Rauschenberg was created in 1959. At the time, the art world was still reeling from Abstract Expressionism—those big, moody drips by guys like Jackson Pollock. Rauschenberg thought that was a bit too much "navel-gazing." He wanted to bridge the gap between art and life.

The eagle is perched on a cardboard box. It looks like it’s flying right at you, emerging from a dark, turbulent background of grey and black paint. Below the eagle, a dirty pillow is tied with a cord, dangling in a way that feels heavy and saggy.

People argue about what it means. Honestly? Rauschenberg usually hated when people over-analyzed his stuff. He’d say things like, "I don't want a painting to look like something it isn't. I want it to look like what it is." But critics can't help themselves. Some see a reference to the Greek myth of Ganymede, where Zeus turns into an eagle and carries off a beautiful boy. The hanging pillow? Maybe it's a butt. Or maybe it's just a pillow. That’s the beauty of a Rauschenberg Combine; it’s a Rorschach test made of trash.

The Materials of a Masterpiece

He didn't go out and buy a pristine eagle. He found it. The story goes that the bird was actually a gift from a fellow artist, Sari Dienes, who had found it in the trash of a neighbor who happened to be an old Rough Rider. It was already a relic.

🔗 Read more: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

- The cardboard box provides a sketchy, fragile pedestal for the bird.

- A photograph of Rauschenberg’s son, Christopher, is tucked into the composition.

- Bits of newspaper and posters are layered under the paint, like urban archaeology.

- The heavy application of paint—thick, dripping, and "messy"—pokes fun at the serious painters of the 1950s.

Why Canyon Still Matters Today

Most art from the fifties feels like a museum piece. It feels "done." But Canyon by Robert Rauschenberg still feels like it’s happening right now. It has this frantic, nervous energy. It’s loud.

It changed the rules. Before the Combines, you were either a sculptor or a painter. Rauschenberg basically said, "Why not both?" He paved the way for Pop Art and everything that followed. Without this bird, you might not have Andy Warhol’s soup cans or the massive, junk-filled installations we see in galleries today. He proved that anything—a tire, a goat, a pillow, or a federal-protected bird—could be high art if you had the vision to frame it.

It's also a reminder of the "stuff" of our lives. We live in a world of discarded objects. Rauschenberg saw the poetry in a discarded box and a dirty pillow. He didn't try to make them look pretty; he tried to make them look important.

A Quick Reality Check on the "Meaning"

If you're looking for a single, definitive answer on what Canyon by Robert Rauschenberg symbolizes, you're going to be disappointed. Art historians like Rosalind Krauss have spent decades dissecting the "flat-bed picture plane" of his work, arguing that it represents how we process information in the modern world—horizontally, like a tabletop or a bulletin board, rather than vertically like a window.

💡 You might also like: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

But Rauschenberg’s genius was his openness. He wasn't a preacher. He was a collector. He gathered the fragments of New York City and glued them together to see what would happen. The work is meant to be felt, not decoded like a secret message from the CIA. It’s about the friction between the three-dimensional bird and the two-dimensional paint.

How to Experience Canyon Properly

If you ever find yourself at MoMA, don't just glance at it and move on to the Starry Night crowd. Stand to the side. Look at how far that bird sticks out into your personal space.

Notice the textures. The wood, the fabric, the feathers. Think about the fact that this specific object caused a multi-year legal war with the federal government. It’s a piece of history that is literally too valuable and too "illegal" to ever be sold.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you want to understand Rauschenberg better, don't start with a textbook. Start with your eyes.

- Look for the "un-artistic": Next time you're in a gallery, look for the materials that don't belong. How does a piece of metal change your mood compared to a stroke of oil paint?

- Research the "Combines": Rauschenberg made a whole series of these. Look up Monogram (the one with the goat and the tire). It’s just as weird and just as brilliant.

- Think about "Found Objects": The next time you see something interesting on the sidewalk, imagine it on a canvas. That’s what Rauschenberg did every single day.

- Visit the MoMA website: They have excellent digital archives that show close-up details of the photographs embedded in the work, which you can't always see clearly behind the museum glass.

Canyon by Robert Rauschenberg isn't just a painting. It’s a collision. It’s the moment where the trash of the street met the halls of the museum, and neither has been the same since. It reminds us that art isn't just something you look at; it's something that occupies the same messy, complicated world we do.