He was obsessive. That’s the first thing you have to understand about Roald Amundsen. While other explorers of the Heroic Age were busy writing poetic diary entries or dying for the sake of "gentlemanly" sportsmanship, Amundsen was basically a machine. He didn't care about the glory of the struggle. He cared about the win.

Most people know him as the guy who beat Robert Falcon Scott to the South Pole in 1911. But honestly, reduces a decade-long career of absolute clinical precision to a single footrace. Amundsen wasn't just a lucky Norwegian who knew how to ski. He was a man who spent years living with the Inuit in the Arctic, learning how to eat raw seal meat to prevent scurvy while the British were still trying to haul heavy sleds by hand like it was some kind of moral test.

He won because he was willing to be "un-British." He used dogs. He wore fur. He planned for failure until failure was impossible.

The Gjöa and the Secret of the Northwest Passage

Before the South Pole was even on his radar, Amundsen did something that had killed hundreds of sailors before him. He found the Northwest Passage. This wasn't a massive naval expedition with thousands of men. It was just Amundsen and six other guys on a 47-ton herring boat called the Gjöa.

They spent three winters in the ice.

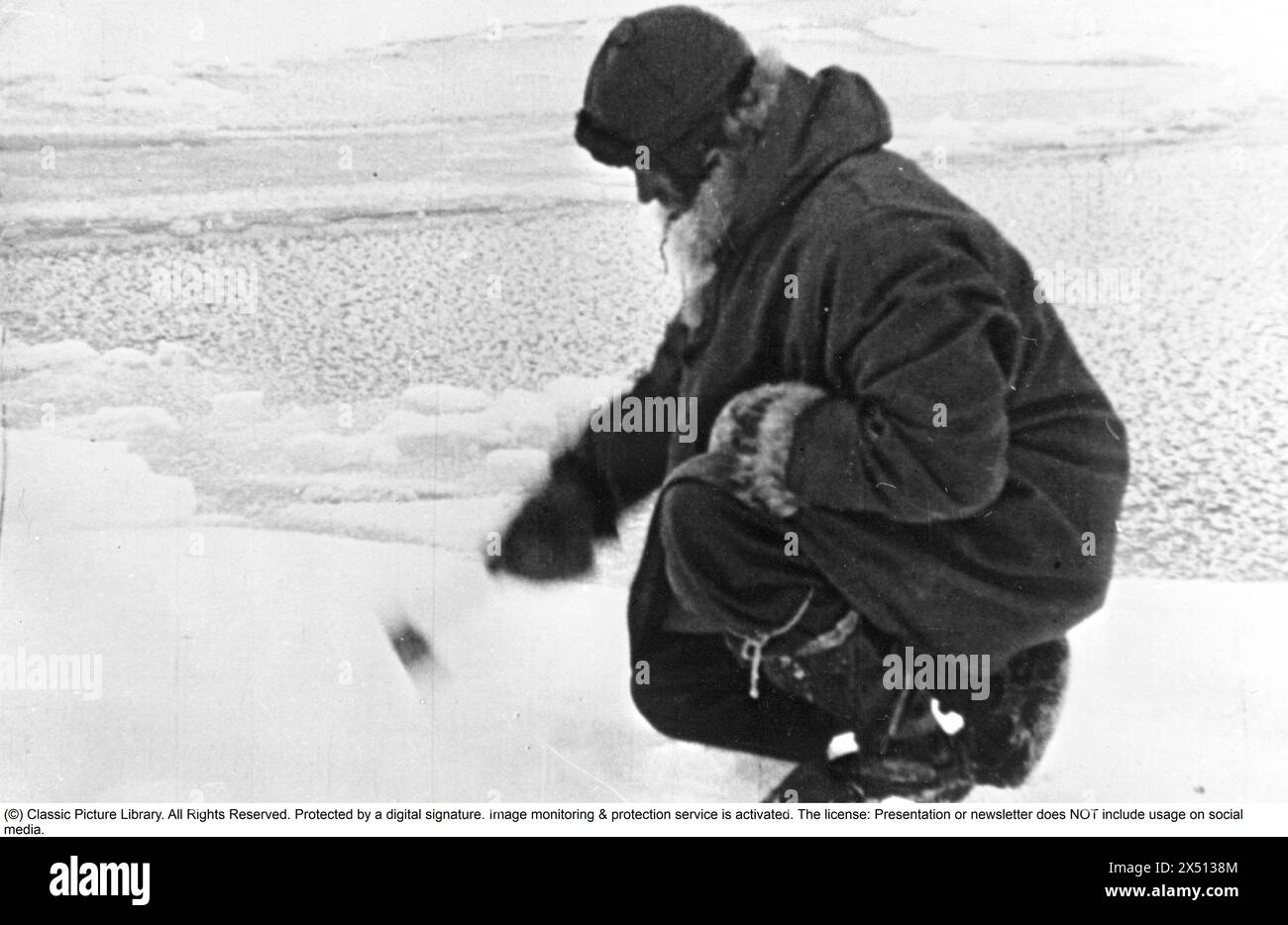

This is where the real Roald Amundsen was formed. While stuck at King William Island, he didn't just sit around playing cards. He watched the Netsilik Inuit. He noticed their clothes weren't heavy wool that soaked up sweat and froze solid. They were loose skins. He saw how they handled dogs. He realized that if you want to survive the most hostile places on Earth, you stop acting like a European and start acting like someone who actually lives there.

He brought that "Inuit mindset" back to Norway. It’s what kept him alive.

The Great Bait and Switch: Why He Went South

Here’s the thing: Amundsen originally wanted the North Pole. He had the ship, the Fram, and the funding. But then news broke in 1909 that Americans Frederick Cook and Robert Peary had already reached the North Pole (or claimed to).

Amundsen was basically broke. He knew that if he told his backers he was changing plans, they’d pull the plug. So he lied. To everyone.

🔗 Read more: City Map of Christchurch New Zealand: What Most People Get Wrong

Even his crew didn't know they were heading to Antarctica until they reached Madeira. He sent a telegram to Robert Falcon Scott: "Beg to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic. Amundsen."

It was a cold move. Very cold. But it set the stage for the most famous race in exploration history.

The Logistics of a Mastermind

While Scott was betting on "motor sledges" (which broke almost immediately) and ponies (which died because, well, they're ponies in the snow), Amundsen bet on 52 Greenland dogs.

- The Sleds: Amundsen had his carpenter, Olav Bjaaland, shave down the weight of the sleds. They went from 165 pounds to about 50 pounds.

- The Food: He didn't just pack "food." He packed calories. He made a special pemmican recipe that included vegetables and oatmeal.

- The Depots: He painted his supply depots with black flags so he could see them in a blizzard. He even laid out markers miles to the left and right of the depots so if he was off-course, he’d still hit a marker.

What Really Happened on the Way to the Pole

On October 19, 1911, Amundsen set off from "Framheim," his base at the Bay of Whales. It wasn't an easy stroll. They had to climb the Transantarctic Mountains, rising over 10,000 feet.

There’s a grit to Roald Amundsen that people often overlook because he made it look "easy." At one point, they reached a glacier so jagged they called it the "Devil’s Glacier." They were crossing crevasses that could swallow a house.

And then there’s the part of the story people don't like to talk about: the dogs.

Amundsen had a plan that was mathematically perfect and ethically brutal. As the sleds got lighter because the food was eaten, he didn't need as many dogs. So, he killed them. He fed the weaker dogs to the stronger dogs and to the men. It sounds horrific to us now, but in 1911, in the middle of a frozen wasteland, it was the difference between life and death.

He reached the South Pole on December 14, 1911.

💡 You might also like: Ilum Experience Home: What Most People Get Wrong About Staying in Palermo Hollywood

He and his four companions—Bjaaland, Hanssen, Hassel, and Wisting—planted the Norwegian flag. They stayed for three days. They took scientific readings. They left a tent, some spare gear, and a letter for Scott, just in case they didn't make it back but Scott did.

They arrived back at their base camp with 11 dogs left. They were actually heavier than when they started because they had eaten so well.

The Controversy of the "Professional" vs. the "Amateur"

When Amundsen got back, the world's reaction was... mixed. The British were furious. They felt he had been "unsporting" by not announcing his intentions. They called him a "professional" as if that was an insult.

To the British elite, Scott’s failure was "heroic" because he suffered. Amundsen’s success was "clinical" because he didn't.

But if you look at the journals of Roald Amundsen, you see a different story. You see a man who was terrified of failure. He was a restless soul who couldn't handle "normal" life. He was constantly in debt. His personal life was a mess of failed relationships and squabbles with his brother, Leon, who managed his finances.

He wasn't a hero in the way we usually think of them. He was a specialist.

The Final Mystery: How Amundsen Disappeared

Amundsen didn't stop at the South Pole. He eventually flew over the North Pole in the airship Norge in 1926. He was the first person to indisputably reach both poles.

But his end was as dramatic as his life.

📖 Related: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

In 1928, an Italian explorer named Umberto Nobile crashed his airship in the Arctic. Nobile and Amundsen actually hated each other. They had a massive falling out over who deserved credit for the Norge flight. But when the call for help came, Amundsen didn't hesitate.

He boarded a French flying boat, the Latham 47, to join the search.

The plane disappeared into the mist over the Barents Sea. A few pieces of debris were found later—a wing float, a fuel tank—but Amundsen’s body was never recovered.

He died in the environment he spent his whole life trying to master. There's something poetic about that, even if Amundsen himself would have probably just called it a navigational error.

Why We Should Still Study Amundsen Today

We live in an age of "disruption" and "optimization," but Roald Amundsen was doing it a century ago. He didn't follow the "industry standards" of his time. He looked at what worked, even if it came from "primitive" cultures that his peers looked down on.

His legacy isn't just a flag in the ice. It's a lesson in preparation.

- Humility in Learning: He spent years learning from the Inuit. He didn't assume his Western education made him superior to the environment.

- Calculated Risk: He wasn't a daredevil. He was a risk manager. Every gram of weight was accounted for.

- Adaptability: When the North Pole was "taken," he didn't give up. He pivoted.

If you want to understand modern exploration—whether it’s going to Mars or diving to the bottom of the Mariana Trench—you’re looking at Amundsen’s blueprint. He proved that survival isn't about how much you can endure; it's about how much you can prevent yourself from having to endure in the first place.

Practical Takeaways from Amundsen's Life

- Audit your equipment. Amundsen spent months manually testing and shaving down his sleds. Most of us use tools every day that are "good enough" but actually slow us down.

- Study the locals. Whether you’re traveling to a new country or starting a new job, the people who have been there the longest have the secrets. Don't reinvent the wheel; ask the person who built it.

- Plan the "Return Trip." Scott’s tragedy was partly because he didn't account for the margin of error on the way back. Always assume the second half of any project will be harder than the first.

- Accept the "Un-heroic" Solution. Sometimes the best way to win is the way that looks the least impressive to others. Using dogs wasn't "brave" in 1911—it was just smart.

Roald Amundsen wasn't looking to be a martyr. He was looking to come home. In the end, that's what made him the greatest explorer of his age. He understood that the goal isn't just to reach the destination; it's to survive the journey so you can tell the story.

To truly appreciate his work, visit the Fram Museum in Oslo. Standing on the deck of the actual ship he used allows you to see the cramped, dark reality of his world. It wasn't a grand adventure; it was a tiny wooden box in a world of white. You can also read his own account, The South Pole, though be warned—he writes like a man who is more interested in the weight of a biscuit than the beauty of the stars. But that, in essence, was the secret to his success.

Actionable Insight: If you're planning a trip to the polar regions today, look for outfitters that emphasize "traditional knowledge" alongside modern tech. Brands like Shackleton or specialized Arctic guides still use the layering principles Amundsen learned from the Inuit. For armchair explorers, compare Amundsen's The South Pole with Scott's Journals: Captain Scott's Last Expedition. The difference in tone—one practical and dry, the other emotional and desperate—tells you everything you need to know about why one man lived and the other died.