It was 1985. Disney decided to make a sequel to the most beloved film in history. They didn't make a musical. They didn't bring back the Technicolor warmth of the 1939 classic. Instead, they gave us Return to Oz, a movie that featured "Wheelers" with wheels for hands and a room full of interchangeable severed heads.

Honestly, it’s a miracle any of us who saw it as kids survived with our sanity intact.

People usually go into Return to Oz expecting "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" vibes, but what they get is a dark, gritty, and surprisingly faithful adaptation of L. Frank Baum’s actual books. Specifically The Marvelous Land of Oz and Ozma of Oz. If you’ve only seen the Judy Garland version, you’ve basically seen the "Disneyfied" version of the lore, even if that one wasn't actually made by Disney. This 1985 cult classic is the real deal. It's weird. It's terrifying. And it’s arguably much closer to what Baum intended.

The Shock of the Opening Act

The movie starts with Dorothy Gale suffering from insomnia. She can’t sleep because she’s dreaming of a magical land that her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry believe is a sign of mental illness. Think about that for a second. We start a "kids' movie" with Dorothy being taken to a clinic for electroshock therapy.

It’s bleak.

💡 You might also like: Why Baby Legs from Rick and Morty is the Peak of Interdimensional Cable

The gray, muddy Kansas landscape is a far cry from the sepia-toned nostalgia we’re used to. Fairuza Balk, in her debut role, plays a Dorothy who looks like she’s actually seen some things. She’s not singing to bluebirds; she’s trying to survive a thunderstorm and a mental institution. When she finally makes it back to Oz, it’s not a celebration. The Yellow Brick Road is shattered. The Emerald City is in ruins. Her old friends have been turned to stone.

This isn't just a sequel. It's a post-apocalyptic reconstruction of a childhood fantasy.

Why the Practical Effects Still Hold Up

We live in an era of CGI sludge. Everything looks like it was rendered on a laptop during a lunch break. But Return to Oz used practical effects that still feel tactile and heavy today. Will Vinton’s "Claymation" (specifically the Nome King) is a masterclass in stop-motion. The way the rocks move and form a face is genuinely unsettling because your brain knows it's a physical object, not just pixels.

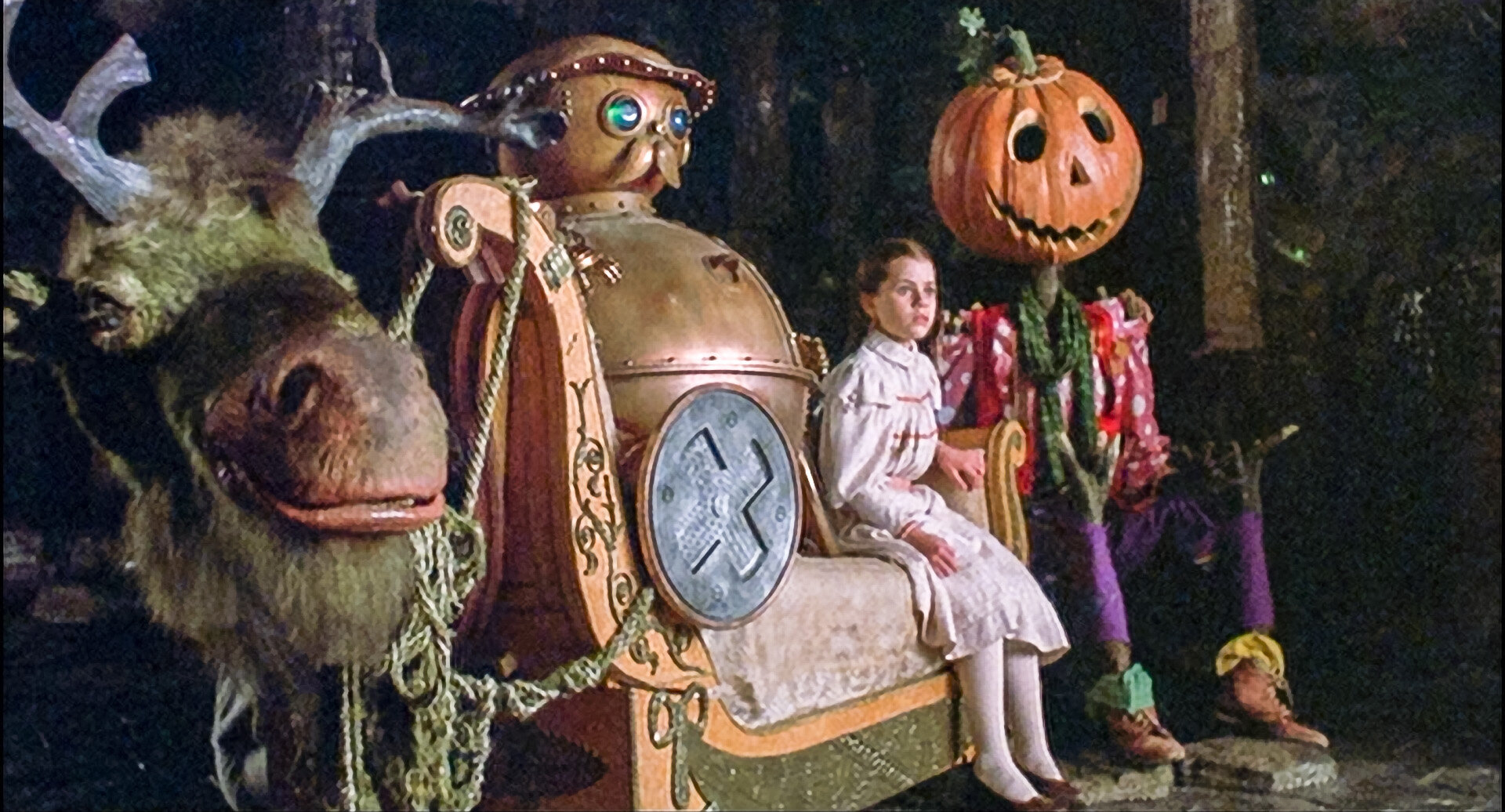

Then you have Tik-Tok. No, not the app. Tik-Tok is the "Royal Army of Oz," a copper, clockwork man who needs to be wound up to think, speak, or move. He’s bulky. He’s clunky. He looks like he weighs five hundred pounds. When he hits something, you feel it.

The Wheelers are another story entirely. These were actors on all fours with wheels attached to their limbs. The sound they make—that high-pitched metallic screeching on the stone pavement—is the stuff of nightmares. There’s a specific kind of craftsmanship here that modern films struggle to replicate. It’s the difference between seeing a ghost on a screen and feeling a cold draft in the room.

Princess Mombi and the Hall of Heads

If you ask anyone what they remember about Return to Oz, they’ll mention the heads. Princess Mombi doesn’t wear jewelry; she wears different heads to suit her mood.

It’s a bizarre, macabre concept that actually comes directly from Baum's writing. The scene where Dorothy has to sneak past the sleeping, headless body of Mombi to steal the Powder of Life is one of the most tense sequences in 80s cinema. When the heads all start waking up and screaming "DOROTHY GALE!" in unison, it’s pure horror.

Why did Disney do this?

Walter Murch, the director, was a legendary sound designer and editor (the guy worked on The Godfather and Apocalypse Now). He had a very specific vision. He wanted to capture the "uncanny" nature of the original illustrations by W.W. Denslow and John R. Neill. He wasn't interested in making a safe movie. He wanted to make a movie that felt like a dream—the kind that shifts into a nightmare before you realize you're even asleep.

The Nome King’s Deadly Game

The climax doesn’t involve a water bucket or a pair of slippers. It’s a psychological game. The Nome King, played with a terrifyingly calm demeanor by Nicol Williamson, challenges Dorothy and her friends to find their transformed companions in his ornament room.

It’s basically a game of "Guess Who" where the stakes are eternal imprisonment as a knick-knack.

What’s fascinating is how the Nome King is portrayed. He’s not a cackling villain in a cape. He’s a force of nature. He represents the earth itself, and he views the emeralds and gold of Oz as his stolen property. There’s a logic to his villainy that makes him far more intimidating than the Wicked Witch ever was. He’s also terrified of eggs. Yes, eggs. It’s a weirdly specific mythological weakness that feels ancient and folk-tale-ish.

The Box Office Failure and the Cult Resurrection

When it came out, the movie bombed. Hard.

Critics hated it. Parents were horrified that their kids were coming home crying. Disney was in a weird transitional period in the mid-80s, trying to find its identity after Walt’s death but before the "Renaissance" of the 90s. They were taking risks with movies like The Black Cauldron and Return to Oz, and audiences just weren't ready for "Dark Disney."

But then came VHS.

Generation X and Millennials discovered it on home video and Disney Channel airings. We realized that while the 1939 film was a beautiful dream, the 1985 film felt like real life—messy, scary, and full of strange creatures that didn't always have your best interests at heart. It gained a reputation as a "forbidden" movie, the one that tested your bravery.

A Masterclass in Production Design

Look at the Gump. It’s literally a couch, some palm fronds, and a mounted elk head tied together with clothesline and brought to life with magic powder. It’s DIY fantasy.

The production designer, Norman Reynolds (who also worked on Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark), created a world that felt lived-in. The ruins of the Emerald City look like actual Roman ruins. The costumes aren't flashy; they're dusty and worn. This groundedness is why the movie works. If the world didn't feel real, the monsters wouldn't be scary.

What Modern Filmmakers Can Learn

There is a lesson here for anyone making fantasy today. You don’t need a $300 million budget and a green screen to create a sense of wonder. You need a perspective.

Return to Oz has a perspective. It treats childhood not as a time of pure innocence, but as a time of profound vulnerability. Dorothy is a girl with no power, caught between an uncaring medical system in the real world and a crumbling empire in the fantasy world. She wins not through magic, but through empathy and stubbornness.

She's the most "human" version of Dorothy we've ever seen on screen.

Actionable Takeaways for Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to revisit this world or dive in for the first time, don't just stop at the movie.

- Read the Books: Specifically The Marvelous Land of Oz and Ozma of Oz. You’ll be shocked at how much of the "scary" stuff in the movie was actually written for children in the early 1900s.

- Seek Out the Blu-ray: The transfers available now (especially the boutique labels) show off the grain and detail of the practical effects in a way that old DVD versions just can't.

- Watch Walter Murch’s Interviews: Hearing him talk about the sound design of the rocks and the Wheelers will give you a whole new appreciation for the technical labor involved.

- Explore the "Dark Fantasy" Era: If you like this, watch The Dark Crystal or Labyrinth. There was a brief window in the 80s where creators were allowed to make "kids' movies" that were actually atmospheric art pieces.

The legacy of Return to Oz isn't just that it scared us. It's that it respected us. It didn't talk down to its audience. It assumed that children could handle the idea of loss, the idea of fear, and the idea that sometimes, you have to fix a broken world yourself.

It remains one of the most singular, visually arresting films in the Disney catalog. It’s a reminder that Oz was never just a dream—it was a place where things could go wrong, and where courage actually meant something. If you haven't seen it in a decade, watch it again. You’ll find it’s even better (and weirder) than you remember.