Ever wonder why some science projects just sort of... flop? It’s usually because someone jumped the gun. Most people think science is just "I have an idea" and then "I did the thing." It's not. If you’ve ever sat through a basic science class, you probably remember a list of steps. But here is the thing: what is the second step of scientific method exactly? It isn’t the hypothesis. It’s not the experiment. Before you start guessing what might happen, you’ve got to do your homework. You have to conduct background research.

It sounds boring. Honestly, it does. But it's the bridge between a wild guess and a brilliant discovery.

The Most Overlooked Part of Doing Science

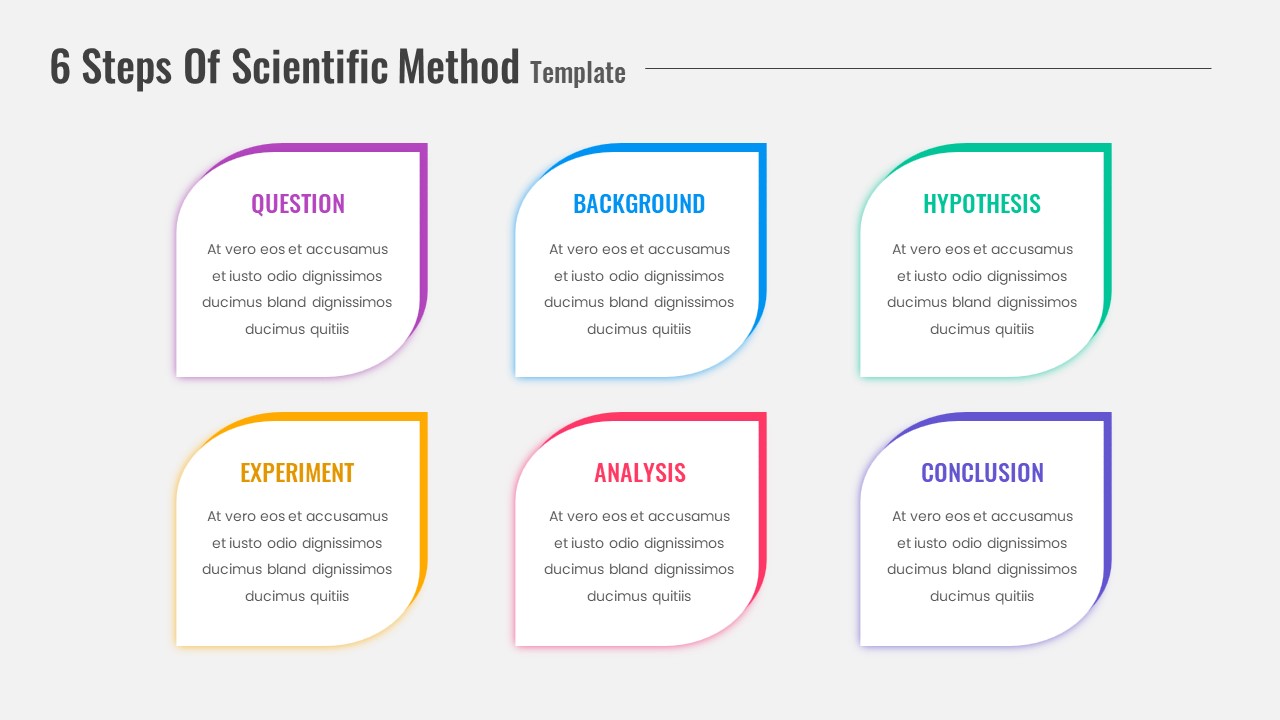

Most textbooks give you a tidy little numbered list. Step one: Ask a question. Step two: Research. Step three: Hypothesis. But in the real world, these steps bleed into each other. If you’re a researcher at a place like NASA or even a high school student working on a science fair project, you can't just skip to the "fun part" of mixing chemicals or coding an AI.

Researching the background is literally about not reinventing the wheel. Imagine spending six months trying to prove that gravity makes things fall down. You’d look like a clown. Why? Because someone already did that. Sir Isaac Newton pretty much handled the heavy lifting there. By looking at what others have done, you refine your question. You might start out asking "Does water affect plant growth?" That’s a bit too broad, right? After some research, you realize that it's more about the acidity of the water or the mineral content. Suddenly, your vague curiosity becomes a sharp, professional inquiry.

This phase is where you look for "prior art." In the patent world, they call it that. In science, it's just called being thorough. You’re looking for variables. You’re looking for what went wrong for the scientists who came before you. If Dr. Smith tried an experiment in 1994 and it blew up in his face, you probably want to know why so you don't repeat the mistake.

Why We Get It Wrong

We love the "Eureka!" moment. We love the idea of Archimedes jumping out of a bathtub or Franklin flying a kite in a thunderstorm. But those stories are kinda misleading. They make it seem like science is just a series of random accidents. It’s not. Archimedes was a mathematician who had been obsessing over displacement for years. He didn't just stumble into the bathtub; he’d been doing the mental "background research" for his entire career.

What is the second step of scientific method? It's the sanity check.

If you skip the research, your hypothesis will be weak. A hypothesis shouldn't be a shot in the dark. It should be an "educated guess." The "educated" part of that phrase comes directly from step two. You read journals. You look at data sets. You talk to experts. You check Google Scholar. Without this, you’re just a person with an opinion, not a scientist with a plan.

Real-World Stakes: When Research Matters

Let’s look at something modern, like the development of mRNA vaccines. People thought they came out of nowhere in 2020. They didn't. Scientists like Katalin Karikó had been doing the "second step" for decades. They were researching how mRNA interacts with cells long before COVID-19 was even a thing. Because they had that massive pile of background research, they could move to the hypothesis and testing phases at lightning speed when the world needed it.

If they had started from scratch in 2020? We’d still be waiting.

💡 You might also like: Gavin Newsom AI Pictures: What Most People Get Wrong About the Legal War Over Deepfakes

Research isn't just about reading, either. Sometimes it involves preliminary observations. You might go out into the field and just watch how a specific bird behaves before you ever try to theorize why it sings at 5:00 AM. You gather the "what" before you try to explain the "why."

The Difference Between Information and Knowledge

There is a trap here. You can’t just Google something for five minutes and call it research. In the age of misinformation, the second step of the scientific method is harder than it used to be. You have to vet your sources.

- Is the study peer-reviewed?

- Who funded the research?

- Was the sample size big enough?

- Is the data from this decade?

A study from 1950 about nutrition might be totally debunked by now. If you base your experiment on old news, your results will be useless. This is why scientists spend so much time in libraries and digital archives. It’s the grunt work that makes the "breakthroughs" possible.

How to Actually Do "Step Two" Right

If you’re working on a project right now, don’t just look for things that prove you’re right. That’s called confirmation bias. It’s the enemy of science. Instead, look for things that might prove you wrong. Look for the anomalies. If everyone says "Option A" always leads to "Result B," but one guy in Sweden found it leads to "Result C," pay attention to that guy. That’s where the new discoveries are hiding.

- Search Broadly: Use databases like PubMed, JSTOR, or ScienceDirect. Don't just stick to the first page of results.

- Check the Bibliography: When you find a good paper, look at their sources. It’s a rabbit hole, but it’s a gold mine.

- Identify Variables: While you’re reading, keep a list of what might affect your experiment. Temperature, time of day, humidity, the brand of equipment used—these are all things you’ll need for your hypothesis later.

- Ask "So What?": If someone already answered your question perfectly, change your question. Find the "gap" in the knowledge.

The Hypothesis Connection

Eventually, you have to stop reading and start doing. You’ll know you’re done with the second step when you can explain your topic to a ten-year-old without getting confused yourself. Once you have that level of clarity, you can write a hypothesis that actually means something. You move from "I think this might happen" to "Based on the work of Miller et al. (2018) and the laws of thermodynamics, I predict that X will cause Y."

See the difference? One is a guess. The other is science.

What is the second step of scientific method? It’s the foundation. You can’t build a skyscraper on sand, and you can’t build a theory on ignorance.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Project

Don't just rush into your experiment. It's tempting, I know. You want to see the reaction or get the data. But if you want your work to be taken seriously—whether it's for a grade, a job, or a publication—you have to respect the process.

Start by dedicatedly searching for the "state of the art" in your specific niche. Write down at least five things that have been proven and three things that are still debated. Use those three debated points to form your question. This ensures you're contributing something new to the conversation rather than just echoing what's already in the textbooks. Check your local library's access to academic journals; many offer free access to databases that would otherwise cost thousands of dollars. Finally, organize your findings in a way that allows you to cite them easily later. Scientific integrity starts with the very first paper you read.

Next Steps for Scientific Success:

- Audit your sources: Ensure every piece of background info comes from a reputable, evidence-based origin.

- Document the "Gaps": Explicitly note what previous researchers didn't find or couldn't explain.

- Draft your variables: List every factor you discovered during research that could possibly skew your results.

- Refine your 'Why': Use your gathered data to justify why your specific experiment is necessary right now.