It was late 1979. Bob Marley was dying. He knew it, even if the world didn't yet. While the rest of the Wailers were leaning into the heavy, electric pulse of reggae’s evolution, Marley sat down with an acoustic guitar. No drums. No bass line to rattle your ribs. Just a man and his wood-and-wire box. What came out was Redemption Song by Bob Marley, a track that felt less like a hit single and more like a final will and testament.

Most people hear it as a campfire anthem. You’ve heard it at every open mic night since 1980. But if you actually listen—honestly listen—it’s a terrifyingly raw piece of music. It’s the sound of someone stripping away the celebrity, the religion, and the politics to find what’s left at the bottom of the soul.

The Secret History of the Lyrics

The song didn't just appear out of thin air. It’s a mosaic. Marley was reading a lot of Marcus Garvey at the time. Specifically, a speech Garvey gave in Menomonie, Wisconsin, in 1937. Garvey said, "We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind."

Marley took those words and turned them into a ghost story.

When he sings about "emancipate yourselves from mental slavery," he isn't just talking about the history of the Atlantic slave trade. He's talking about the internal chains we forge every day. He was dealing with cancer in his toe that had spread to his lungs and brain. He was physically trapped by his own body, yet he was singing about the ultimate freedom. It’s heavy stuff.

Why the Acoustic Version Almost Didn't Happen

Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records, was the one who pushed for the acoustic arrangement. There is a full band version—it’s on the Uprising deluxe editions—and it’s... fine. It’s a standard reggae shuffle. But Blackwell heard the solo demo and realized that the band actually got in the way of the message.

🔗 Read more: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

Sometimes, less is more.

By removing the rhythm section, Marley forced the listener to look him in the eye. You can hear his fingers sliding across the strings. You can hear the slight rasp in his throat. It’s intimate in a way that "Could You Be Loved" or "Jamming" never tried to be. It’s the difference between a parade and a confession.

Redemption Song by Bob Marley as a Cultural Survival Kit

This isn't just a song; it’s a toolkit for survival. It has been adopted by every movement from the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa to modern protests in the streets of New York and London. Why? Because it doesn't promise an easy victory.

Marley asks a haunting question: "How long shall they kill our prophets while we stand aside and look?"

He doesn't give an answer. He just says some say it’s part of the plan. That’s a cynical, weary observation for a man who spent his life preaching "One Love." It shows a side of Marley that gets airbrushed out of the t-shirts and posters. He was frustrated. He was tired. He saw the cycle of violence repeating and he was calling us out for watching it happen.

💡 You might also like: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

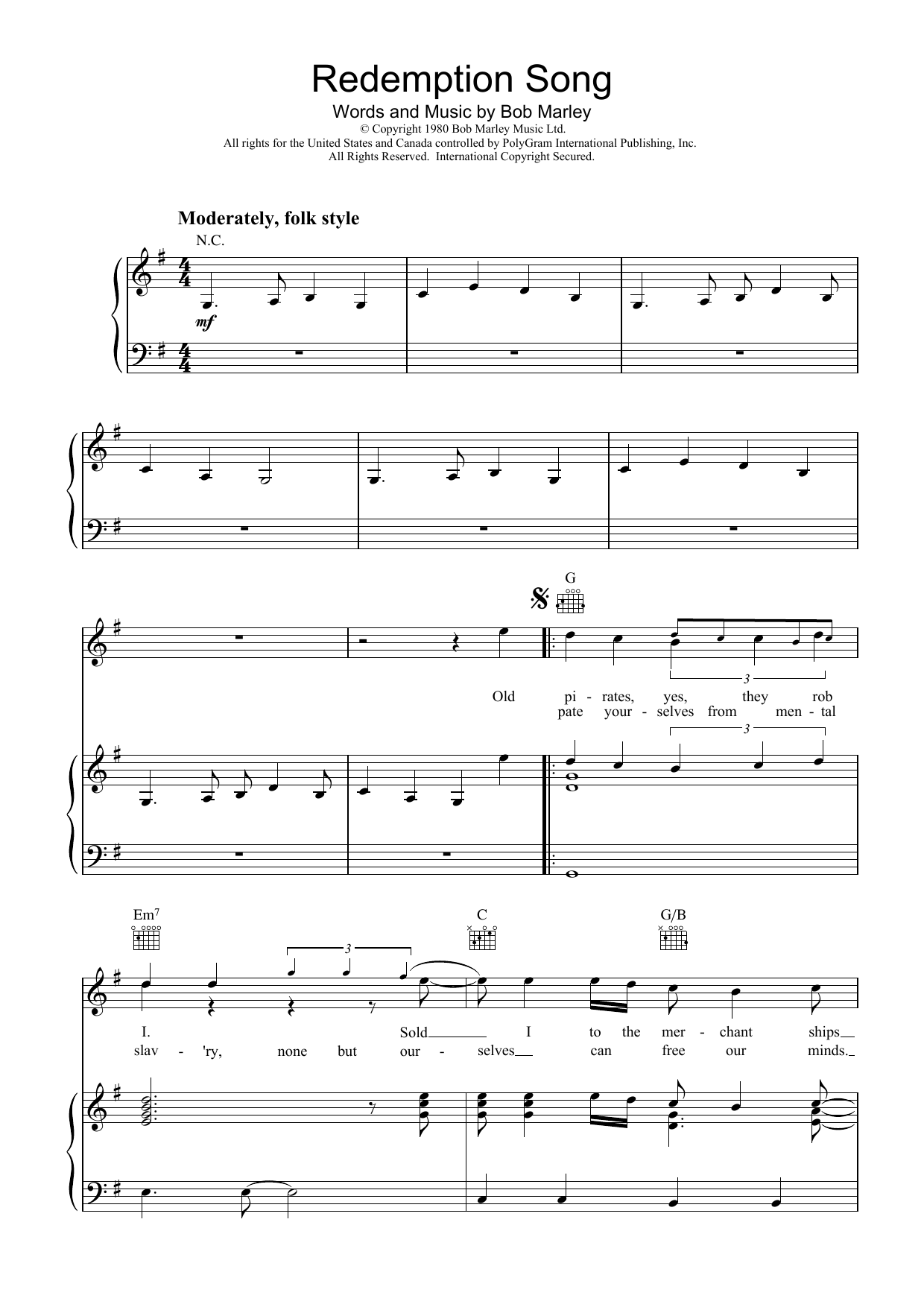

The Technical Brilliance of Simplicity

Musically, the song is built on a standard G-Em-C-Am progression. It’s Folk 101. But the way Marley phrasing his vocals—the "redemption songs" refrain—uses a melodic lift that feels like climbing a hill.

- The Intro: That iconic descending bass line played on the low strings of the acoustic guitar. It’s instantly recognizable within three notes.

- The Tempo: It breathes. It’s not locked to a metronome. It speeds up and slows down based on the emotional weight of the words.

- The Production: It’s dry. There’s almost no reverb. It sounds like he’s sitting three feet away from you in a room with wooden floors.

If you compare this to the disco-influenced production of other 1980 tracks, it’s an anomaly. It shouldn't have worked. It should have been too "boring" for the radio. Instead, it became the definitive closing statement of the 20th century’s most important reggae artist.

Common Misconceptions About the Meaning

A lot of people think this is a song about peace. It’s not. Not really. It’s a song about sovereignty.

There’s a huge difference. Peace is the absence of noise; sovereignty is the presence of power over one’s own life. When Marley sings "Have no fear for atomic energy / 'Cause none of them can stop the time," he’s dismissing the entire Cold War power structure. He’s saying that the geopolitical giants of the era—the US and the USSR—are irrelevant compared to the spiritual timeline of humanity.

It’s an incredibly bold thing to say. It’s almost cocky. And yet, coming from a man who was literally fading away, it carries the weight of a prophecy.

📖 Related: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

How to Truly Appreciate the Track Today

If you want to understand Redemption Song by Bob Marley, stop listening to it as background music while you do the dishes.

- Find the original 1980 Uprising vinyl or a high-quality lossless stream.

- Get some decent headphones.

- Listen for the "click" of his plectrum.

- Focus on the verse about the "bottomless pit."

That line—"Old pirates, yes, they rob I / Sold I to the merchant ships"—isn't just history. Marley was looking at the music industry, at the politicians in Jamaica who tried to assassinate him in 1976, and at the doctors who couldn't save him. He was the one in the pit, and the song was his ladder out.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Listener

To get the most out of this masterpiece and understand its place in history, you should explore the context surrounding its birth.

- Read the Garvey Speech: Look up Marcus Garvey's 1937 Menomonie speech. Seeing the raw text Marley adapted puts his songwriting genius into a new perspective.

- Listen to the Band Version: Seek out the "Band Version" on the Uprising remastered album. It’s a fascinating look at what the song could have been and why the acoustic choice was a stroke of genius.

- Watch the 1979/80 Live Footage: There are snippets of Marley performing toward the end. His physical frailty contrasts with the vocal power, proving that the "mental" freedom he sang about was something he was actively practicing.

- Check Out the Covers: Listen to Johnny Cash and Joe Strummer’s version. It’s crusty and weathered. Then listen to Lauryn Hill’s version. Each artist finds a different "mental slavery" to fight against, which proves the song’s universal utility.

The legacy of this track isn't in its chart position or its sales. It’s in the fact that when things get truly dark—personally or politically—this is the song people turn to. It’s a reminder that while you can’t always control your circumstances, you are the only one with the keys to your own mind. That’s the real redemption.

The song doesn't end with a fade-out. It ends with a sharp stop. A finality. Bob Marley died less than a year after it was released. He didn't need to say anything else.

Key Takeaway: To fully grasp the song, study the Marcus Garvey influence and compare the acoustic version to the full band recording to see how Marley used "silence" as an instrument.