Fear is weirdly personal. You might think a giant monster is terrifying, while I’m over here losing my mind because a door in a quiet room creaked open just an inch. That's the beauty—or the nightmare—of really scary short stories. They don't have three hundred pages to build a world. They have to grab you by the throat in the first paragraph, squeeze, and then leave you staring at your bedroom ceiling at 3:00 AM wondering if that shadow in the corner just moved.

The best ones aren't just about gore. Honestly, blood is easy. Anyone can write a slasher. But to write something that actually lingers? That takes a specific kind of psychological surgery. You’ve got to tap into the "uncanny," that feeling where something is almost normal, but just slightly off. Think about the works of Shirley Jackson or Alvin Schwartz. They understood that the most frightening thing isn't the monster under the bed; it's the realization that the person sitting across from you at dinner might not be who they say they are.

The Architecture of a Nightmare

What actually makes a story stick? It's usually the "gap." This is the space between what the character sees and what the reader understands. In many really scary short stories, the horror isn't explained. Explanation is the death of fear. Once you know the ghost is just a Victorian lady looking for her lost locket, the mystery is gone. You’re bored. But if the ghost is just a pair of wet footsteps that stop right behind your chair? That’s staying with you forever.

Varying the pace is a writer's best weapon. A long, descriptive sentence can lul you into a false sense of security, making you feel the heavy atmosphere of a dusty library or a fog-choked street. Then—snap. A short sentence breaks the rhythm. It’s a jump scare in text form.

Take "The Monkey’s Paw" by W.W. Jacobs. It’s a classic for a reason. It doesn't show you the mangled corpse of the son coming back to life. It just gives you a frantic knocking at the door. The horror is entirely in your own head. Your brain is a much better special effects department than any Hollywood studio. It knows exactly what scares you most, and Jacobs just gives you the blank canvas to project it onto.

Why We Can't Stop Reading Them

It seems counterintuitive. Why would we want to be scared? Psychologists like Dr. Glenn Walters have talked about the "triple threat" of horror: tension, relevance, and unrealism. We get a massive rush of adrenaline and dopamine, but our brains know we’re safe on our couch. It’s a biological cheat code.

But there’s more to it than just a chemical spike. Really scary short stories often act as a pressure valve for societal anxieties. In the 1950s, horror was all about nuclear radiation and "the other." Today, a lot of effective short fiction focuses on isolation, the loss of privacy, or the terrifying realization that our technology might be watching us back.

Look at the "Creepypasta" phenomenon. Stories like "The Russian Sleep Experiment" or "Penpal" didn't start in prestigious literary journals. They started on message boards. They feel like modern folklore. They’re messy, sometimes poorly edited, and raw. That lack of professional polish actually makes them feel more authentic, like a warning from a friend rather than a polished piece of fiction. It taps into that "friend of a friend" legend vibe that makes your skin crawl.

The Masters of the Short-Form Shiver

If you want to understand the genre, you have to look at the people who defined it. H.P. Lovecraft gets a lot of flak for his prose—which, let’s be real, is pretty dense—but he mastered the idea of "cosmic horror." The idea that we are tiny, insignificant specks in a universe filled with ancient, uncaring gods. It’s a cold kind of fear.

On the flip side, you have Ray Bradbury. He wrote some of the most unsettling, really scary short stories by focusing on the nostalgic and the mundane. "The October Game" is a perfect example. It starts as a simple Halloween party and ends with a realization so grim it makes your stomach drop. He didn't need tentacles or aliens; he just needed a darkened room and a game of "pass the body parts."

Then there's the modern queen of the short story, Mariana Enriquez. Her work, like "The Dangers of Smoking in Bed," blends Argentine history and social inequality with bone-chilling supernatural elements. She proves that horror is most effective when it’s grounded in a reality we recognize. When the ghost is haunting a neighborhood that's already suffering from poverty or political unrest, the stakes feel much higher.

Common Misconceptions About Horror Writing

- It needs a twist ending: Not really. Sometimes the most terrifying ending is the one you see coming from a mile away, and you're just powerless to stop it.

- Jump scares don't work in print: They do. It’s all about sentence structure and page turns.

- Gore equals scary: Nope. Gore is often just gross. True horror happens in the mind's eye.

How to Find Stories That Actually Scare You

Searching for "scary stories" on Google often leads to the same five recycled lists. If you want the deep cuts, you have to look toward specialized anthologies. The "Best New Horror" series, edited by Stephen Jones, is a gold mine. So are magazines like Nightmare Magazine or The Dark.

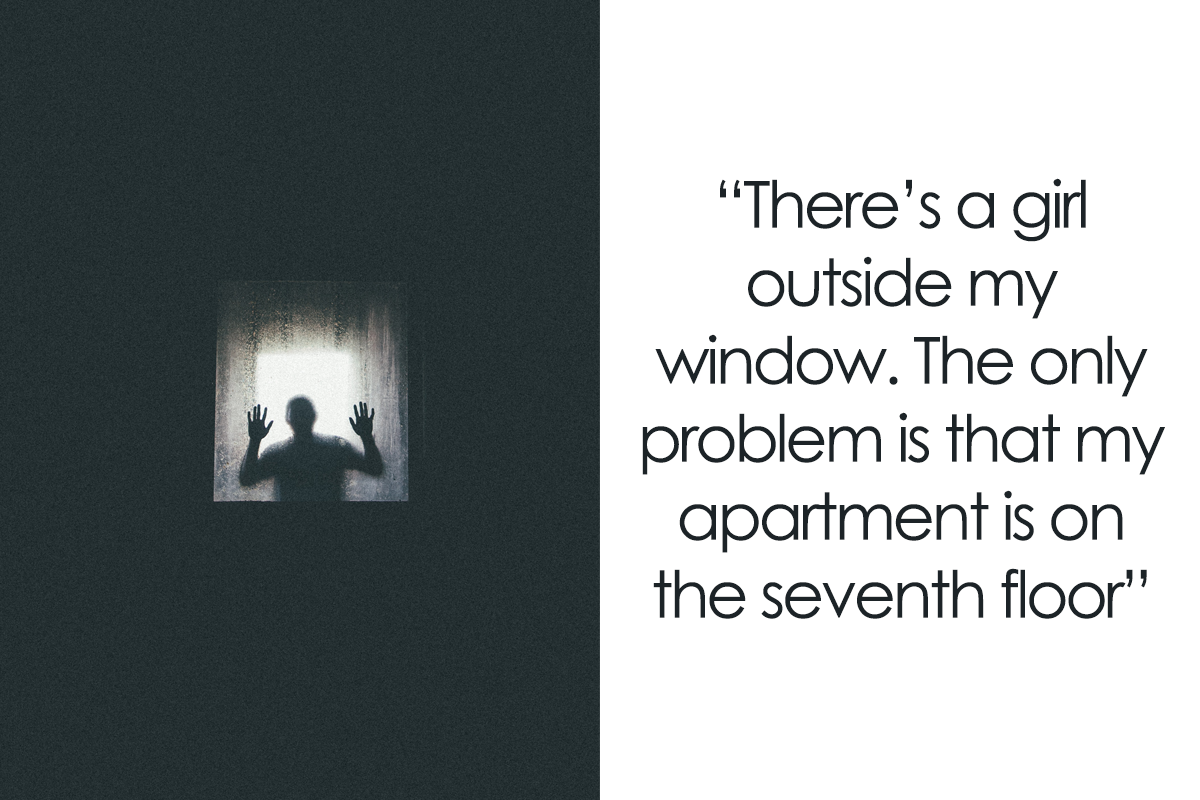

Don't ignore the "Two Sentence Horror" subgenre either. It’s a fantastic exercise in minimalism.

"I can't sleep," she whispered as she stepped into bed with me. I woke up cold, remembering that I’d buried her yesterday.

It’s a trope, sure. But it works because it relies on a universal fear: the dead not staying dead.

The Evolution of the "Short" in Short Story

We're seeing a shift in how these stories are consumed. It's not just books anymore. It's podcasts like The Magnus Archives or Knifepoint Horror. These formats lean into the oral tradition of storytelling. Hearing a calm, steady voice describe something horrific creates a weird intimacy. It feels like you’re being told a secret you weren't supposed to hear.

This digital evolution has also given rise to "analog horror" on platforms like YouTube. While these are visual, they are essentially really scary short stories told through the medium of grainy VHS footage and cryptic text. They rely on the same principles: less is more, the unknown is terrifying, and the familiar should never be trusted.

Actionable Steps for the Horror Aficionado

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world or even try your hand at writing your own, here is how you should actually approach it:

✨ Don't miss: The Traveler 2010 Film: Why This Val Kilmer Horror Mystery Is Still So Polarizing

1. Read outside your comfort zone.

If you usually like ghost stories, read some "body horror" by Clive Barker. If you like psychological thrillers, try the weird, experimental fiction of Robert Aickman. Expanding your vocabulary of fear makes the experience much richer.

2. Pay attention to your "micro-fears."

What’s that one specific thing that makes you nervous? Is it the sound of a humming refrigerator? The way a mannequin looks when the lights are low? Those tiny, specific details are what make a story feel real. Use them.

3. Study the "Turn."

In almost every effective short horror piece, there is a moment where the tone shifts. Analyze where that happens. Is it a line of dialogue? A sudden change in the weather? Mapping out how a writer builds and then breaks tension is the best way to understand the craft.

4. Check out local folklore.

The best really scary short stories are often the ones that feel like they belong to a specific place. Look into the legends of your own town or region. There’s usually something dark hiding in the local history books that hasn’t been overused by Hollywood yet.

5. Limit your intake.

This sounds weird, but don't binge-read horror. If you read ten scary stories in a row, you become desensitized. Read one. Let it sit. Let your mind wander into the dark corners of the room. That’s where the real story happens anyway.

The most enduring stories are the ones that reflect our own vulnerabilities back at us. They remind us that the world is a lot bigger, and a lot stranger, than we like to admit. Whether it's a classic tale from a century ago or a viral post from last week, a truly frightening story doesn't just end when you close the book. It stays in the room with you.