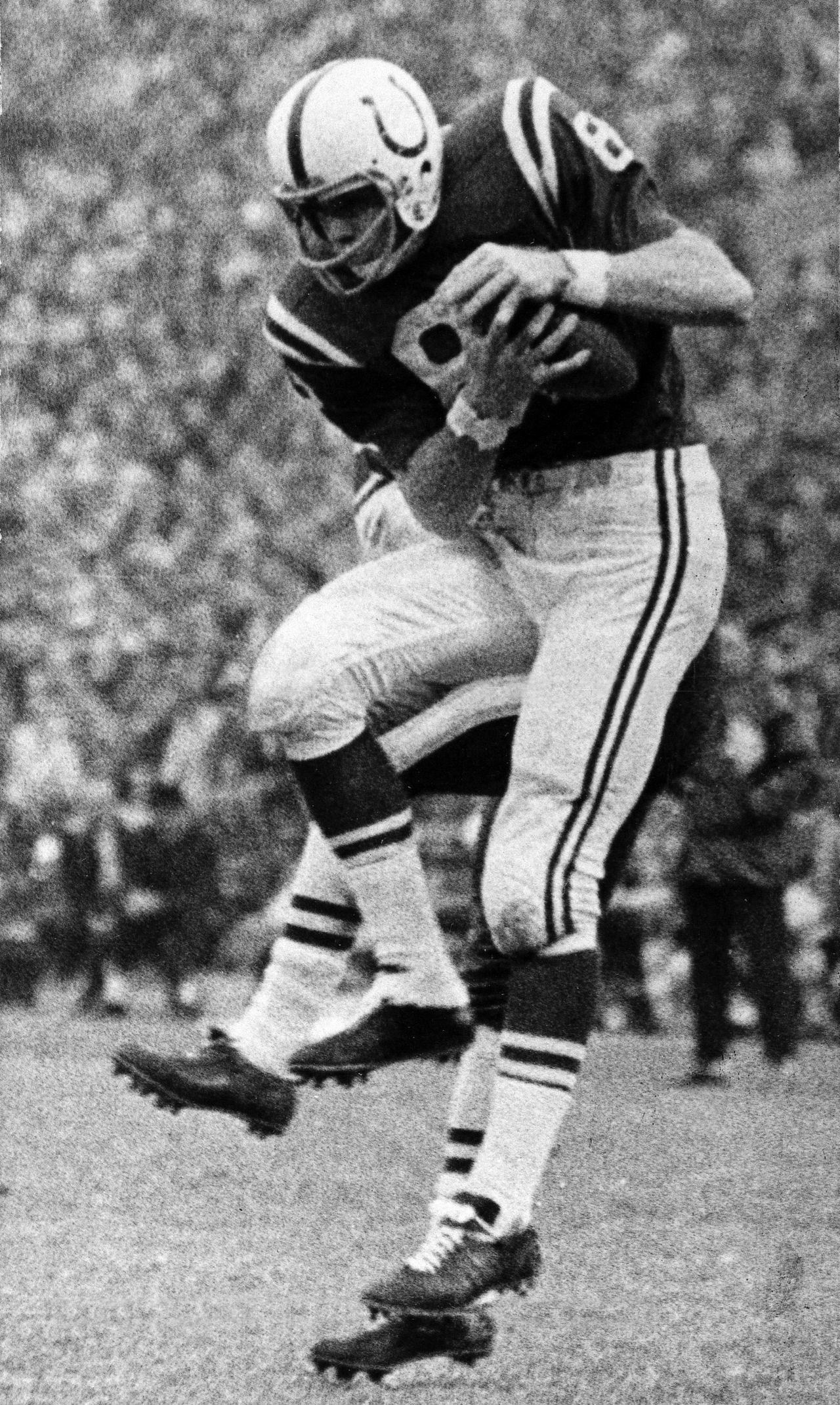

Raymond Berry wasn't supposed to be famous. Honestly, if you looked at him in 1954, you probably wouldn't have even picked him for your local flag football team. He had one leg shorter than the other. His eyesight was so bad he had to wear thick glasses (and eventually some of the earliest contact lenses) just to see the ball. He wasn't fast—clocking a 4.8-second 40-yard dash—and he wasn't particularly big.

Yet, this man became the blueprint for every modern wide receiver you see today.

When people talk about the greatest to ever play the position, the names Jerry Rice or Randy Moss usually fly out first. But if you ask the old-timers or the real film junkies about Raymond Berry, they'll tell you he was the one who turned pass-catching into a science. He didn't just play football; he engineered it.

The 20th Round Longshot

The Baltimore Colts took a flyer on Berry in the 20th round of the 1954 NFL Draft. Let that sink in for a second. There aren't even 20 rounds anymore. He was the 232nd overall pick. Most guys drafted that late are lucky to make the practice squad for a week before getting a "real job" at a hardware store.

But Berry had this weird, almost frightening level of focus.

He knew he couldn't outrun anyone. He couldn't jump over them. So, he decided he would simply never be in the wrong place. He developed a catalog of 88 different releases and breaks. Eighty-eight! He’d spend hours after practice—long after the stars had headed to the bars for a beer—working with ball boys or even his wife in the backyard, just to perfect a three-step slant.

📖 Related: U of Washington Football News: Why Jedd Fisch’s Roster Overhaul Is Working

Why the Raymond Berry and Johnny Unitas Connection Worked

You can't talk about Berry without mentioning Johnny Unitas. They were like two mad scientists locked in a lab. In 1956, when Unitas joined the Colts, the game changed forever.

They didn't just run plays; they ran "options" before that was even a buzzword. They had a psychic connection. Berry would tell Unitas exactly where he’d be based on the defender's hip movement, and the ball would be there before Berry even turned his head.

The "Greatest Game Ever Played"

If you need one reason why Raymond Berry is a legend, look at the 1958 NFL Championship Game. Most people remember Alan Ameche’s winning touchdown in overtime. But the Colts don’t even get to overtime without Berry.

He caught 12 passes for 178 yards and a touchdown. That was a title-game record that stood for over half a century. On the final drive in regulation, with the Colts trailing the New York Giants, Berry caught three straight passes. It was like he was playing against air. He was so precise, so reliable, that the Giants' secondary looked like they were running in sand while he moved in high definition.

The Statistics of a Perfectionist

Look at the numbers, because they don’t lie. Over 13 seasons, all with the Baltimore Colts, he put up:

👉 See also: Top 5 Wide Receivers in NFL: What Most People Get Wrong

- 631 receptions

- 9,275 yards

- 68 touchdowns

- Only two fumbles in his entire career

Think about that. In an era where the ball was like a water-logged melon and defenders could basically tackle you before the pass arrived, he fumbled twice in 13 years. That’s not luck. That’s a man who gripped the ball like it was his firstborn child.

He led the league in receptions three times in a row (1958-1960). In 1959, he won the "Triple Crown" of receiving—leading the NFL in catches, yards, and touchdowns. It’s a feat so rare that only a handful of guys like Steve Smith and Cooper Kupp have done it since.

Beyond the Playing Field

After he hung up the cleats in 1967, Berry didn't just disappear to a golf course. He took that same obsessive brain into coaching. Most people remember him leading the New England Patriots to Super Bowl XX in 1985.

Even as a coach, he was different. He didn’t scream. He taught. He treated wide receivers like craftsmen. He wrote a book called Raymond Berry’s Complete Guide to Coaching Pass Receivers, which is basically a Bible for the position. It’s not a fun read—it’s a manual. It’s dry, technical, and brilliant.

The Human Element: Grit and Back Braces

What’s sort of crazy is that Berry played most of his career in a back brace. He had a congenital condition that made every hit feel like a car crash. He wore special shoes to balance out his legs. He was basically held together by tape, willpower, and a deep-seated desire to prove everyone wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Tonya Johnson: The Real Story Behind Saquon Barkley's Mom and His NFL Journey

He’s often called "Old Reliable." It’s a bit of a boring nickname, but it fits. In 1973, he was a first-ballot Hall of Famer, and rightfully so.

What We Can Learn From Berry Today

We live in an era of 4.3 speed and acrobatic one-handed grabs that go viral on TikTok. But Raymond Berry reminds us that preparation is a talent in itself. He proved that if you out-work, out-study, and out-think the guy across from you, you don't need to be the fastest person on the field.

If you’re a young athlete or just someone trying to get better at your craft, Berry’s life offers a pretty clear roadmap:

- Master the fundamentals: Don't worry about the highlight reel until you've mastered the footwork.

- Preparation kills anxiety: He fumbled once every six years because he practiced ball security until it was muscle memory.

- Find your "Unitas": Collaboration works best when both people are equally obsessed with the details.

- Ignore the "scouting report": If people say you're too slow or too small, find another way to win.

Raymond Berry passed the torch to guys like Jerry Rice, who famously adopted a similar "stay late at practice" mentality. When you see a receiver today run a route so crisp that the cornerback falls over, you're seeing the ghost of number 82 in Baltimore. He basically invented the "move" that gets receivers open today.

Start by looking up old film of the 1958 Championship. Watch how he sets up his defender. It’s a masterclass that’s still relevant 70 years later.

If you want to understand the modern NFL, you have to understand why a guy with bad eyes and a limp became the greatest of his generation. It wasn't magic. It was just a lot of hours in a backyard in Texas, catching passes until the sun went down.