You’re driving. It’s 2:00 AM. The highway is a black ribbon stretching into nowhere, and suddenly, that propulsive, churning bass line kicks in. You know the one. It feels like a heartbeat, but faster. Radar Love by Golden Earring isn’t just a song; it’s a physical experience. Honestly, if you haven’t accidentally gone ten miles over the speed limit while this track was playing, have you even lived?

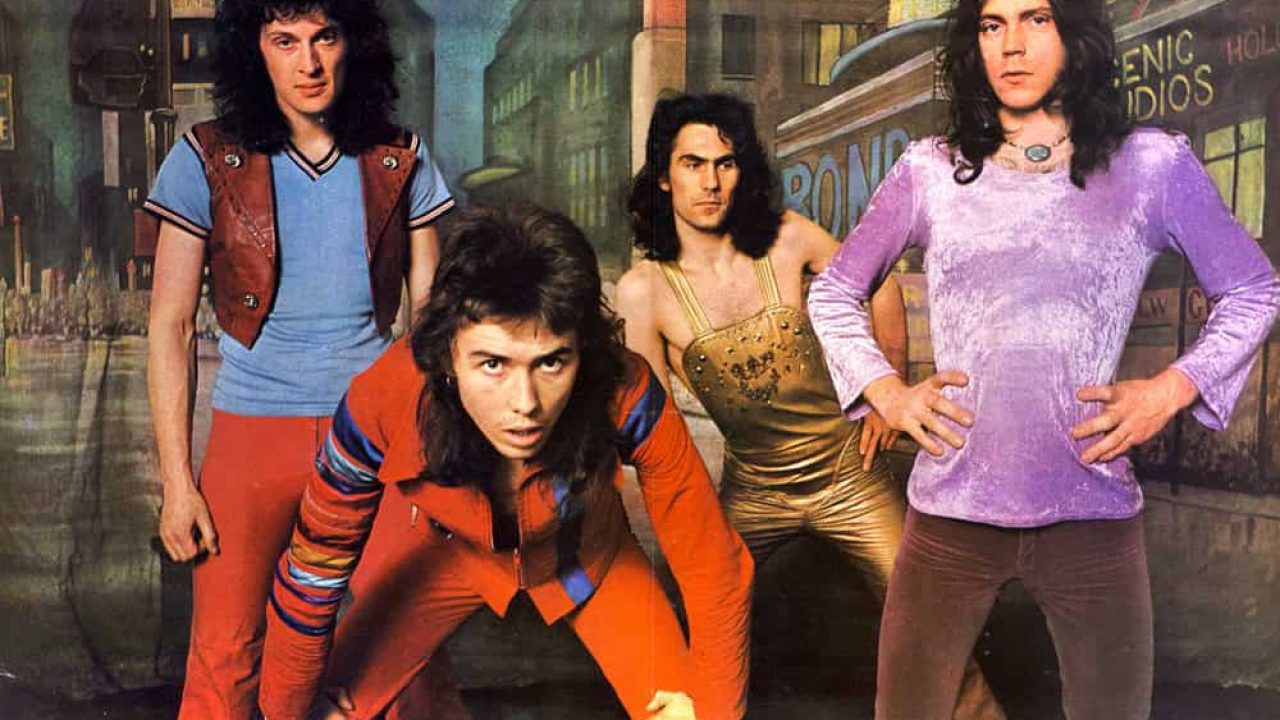

It’s been over fifty years since this Dutch quartet—George Kooyans, Barry Hay, Rinus Gerritsen, and Cesar Zuiderwijk—conquered the world with a song about psychic connection and high-speed travel. But why does it still hold up? Most "classic rock" feels like a museum piece, dusted off for nostalgia's sake. This song feels like it’s happening right now. It captures a specific kind of desperation. A kinetic energy.

The Secret Sauce of the Radar Love Rhythm Section

Most people think they love the song because of the lyrics or that catchy "Coming to you girl" hook. They’re wrong. They love it because of Rinus Gerritsen’s bass.

Gerritsen didn't just play a rhythm; he created a machine. Most rock songs of the early 70s were either bluesy and loose or heavy and plodding. Radar Love by Golden Earring opted for something different: a driving, syncopated gallop. It’s almost proto-disco in its steadiness, but it has the grit of a garage band.

And then there's Cesar Zuiderwijk.

The drum solo in the middle of the track is legendary for a reason. During live shows, Zuiderwijk would famously leap over his drum kit at the climax. It wasn't just showmanship. It reflected the sheer, unbridled momentum of the music. When you listen to the studio version, pay attention to the hi-hat work. It’s frantic. It mirrors the feeling of a driver’s foot tapping nervously on the gas pedal.

Why the Horns Actually Work

Adding a brass section to a hard rock song in 1973 was a massive gamble. Usually, it makes a track sound "show-tuney" or soft. Not here. The horns in Radar Love sound like sirens. They add a layer of anxiety and urgency. It’s a sonic representation of the "radar" mentioned in the title. They cut through the mix like headlights through fog.

Breaking Down the Narrative: More Than Just a Car Song

Barry Hay’s vocals sell the story. It’s a simple premise: a guy is driving all night to get to his woman because they have a "psychic" connection. He doesn't need a phone. He doesn't need a letter. He just knows she wants him there.

🔗 Read more: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

"I’ve been driving all night, my hand’s wet on the wheel."

That line is visceral. We've all been there—tired, caffeinated, focused on a singular goal. But there’s a darker undercurrent. Some fans and critics have argued over the decades that the song isn't just about a romantic reunion. Given the intensity of the music and the "radio’s playing some forgotten song" line, there’s a sense of isolation that borders on the supernatural. It’s a lonely song.

Think about the lyrics for a second. The narrator talks about the "shift-clock" and "the lines on the road." He’s in a trance. Golden Earring managed to bottle the feeling of highway hypnosis. You’re awake, but your brain is in a different dimension.

The Dutch Invasion That Actually Stuck

Before Radar Love by Golden Earring, the "Dutch Invasion" wasn't exactly a thing. Sure, you had Shocking Blue with "Venus," but Golden Earring brought a level of technical proficiency that rivaled Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple.

They were huge in Europe long before America noticed. In fact, they’d been around since the early 60s, starting as a beat band called The Golden Earrings. By the time they recorded the Moontan album, they had evolved into a sophisticated prog-rock-meets-hard-rock hybrid.

Producer Fred Haayen deserves a lot of credit for the track's longevity. He captured a "wide" sound. If you listen on a good pair of headphones, the stereo separation is incredible. The guitar pans, the echoing vocals, the way the bass sits right in the center of your skull. It was ahead of its time.

The Misconceptions About the Cover Versions

Everyone has covered this song. White Lion did a hair-metal version in the late 80s that some people (inexplicably) prefer. U2 has played it live. Bryan Adams, Def Leppard, even James Last.

💡 You might also like: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

But here is the truth: nobody captures the "swing."

Most covers make it too heavy. They turn it into a straight 4/4 stomp. But the original has a slight "shuffle" to it. It’s a bit "swingy." That’s the influence of Rinus Gerritsen’s jazz background. If you take the swing out, you lose the "rolling" feeling of the tires on the pavement. You just end up with a loud rock song. The original is a moving rock song.

Technical Nuance: The Gear Behind the Sound

For the gear nerds out there, the sound of Radar Love by Golden Earring is a masterclass in 70s analog warmth. George Kooymans used a Gretsch White Falcon for much of his career, which provided that twangy but thick lead tone.

Rinus Gerritsen often played a self-built double-neck bass and guitar or a Danelectro. That specific "clack" in the bass tone? That’s the Danelectro. It’s thin, punchy, and cuts through a car radio better than a muddy Fender Precision would have at the time.

And let’s talk about the "vocal fry" before it was a thing. Barry Hay’s delivery is incredibly relaxed. He’s not screaming. He’s telling you a story. It’s conversational. It makes the listener feel like they’re in the passenger seat.

The Legacy of the Ultimate "Driving Song"

In many polls, including those by Top Gear, this track consistently ranks as the greatest driving song of all time. It beat out "Born to Be Wild." It beat out "Highway Star."

Why? Because it mimics the act of driving.

📖 Related: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

The song has gears. It starts in low gear with that intro. It shifts up during the verses. The chorus is the overdrive. The middle break is the long stretch of desert road where your mind wanders. Then, the final chorus is the sprint to the finish line.

It’s structural perfection.

How to Truly Appreciate the Track Today

If you want to experience the song the way it was intended, you need to find the full album version. The radio edit chops out the heart of the instrumental build-up. You need those six-plus minutes. You need to hear the way the song breathes.

Interestingly, the band never quite topped this success in the States, though "Twilight Zone" was a massive hit in the MTV era. But they didn't need to. This one song cemented their place in the DNA of rock and roll. It’s played every single day, somewhere in the world, on a classic rock station, and nobody ever reaches for the dial to turn it down.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Listener

If you’re a musician or a fan looking to get more out of this classic, here’s how to approach it:

- Analyze the Bass-Drum Interplay: Don’t just listen to the melody. Focus entirely on the bass and kick drum. Notice how they rarely step on each other. It’s a lesson in "pocket" playing.

- Check Out the Live Versions: Find footage of Golden Earring from the mid-70s. Their energy was significantly higher than their studio recordings suggest.

- Explore the "Moontan" Album: Don't stop at the hit. Tracks like "Candy's Going Bad" show the band's range. They were much heavier and more experimental than the "one-hit wonder" tag (which is false anyway) suggests.

- Acoustic Appreciation: Look for the "Naked" live acoustic versions the band did later in their career. Stripping away the electricity proves just how strong the songwriting actually is.

The next time you find yourself on a long stretch of highway at night, put on Radar Love by Golden Earring. Don't just play it as background noise. Turn it up until the car vibrates. Feel the way the bass mimics the road. You’ll realize that while technology has changed—we have GPS and Spotify now—the primal urge to get "home" to someone, fueled by a high-octane soundtrack, is exactly the same as it was in 1973.