It’s been nearly a century since Private Lives by Noel Coward first hit the stage, and honestly, it’s still probably the meanest, funniest, and most honest look at toxic relationships ever written. People call it a "comedy of manners." That's a bit of a polite lie. It's more like a comedy of bad manners. It’s about two people who can’t live with each other and can’t live without each other, which is a trope we see everywhere now—from Marriage Story to every second sitcom on Netflix—but Coward did it first, and he did it with a silk dressing gown and a cigarette in hand.

The play is famous for being written in a four-day fever dream in a hotel in Shanghai. Coward had the flu. He was 30. He was already a superstar. He wrote this vehicle for himself and his best friend, Gertrude Lawrence, and it basically redefined what modern dialogue sounded like. Before this, stage talk was often stiff, formal, or overly poetic. Coward changed the game. He used short, clipped sentences. He used silence. He understood that what people don't say is usually way more important than what they do.

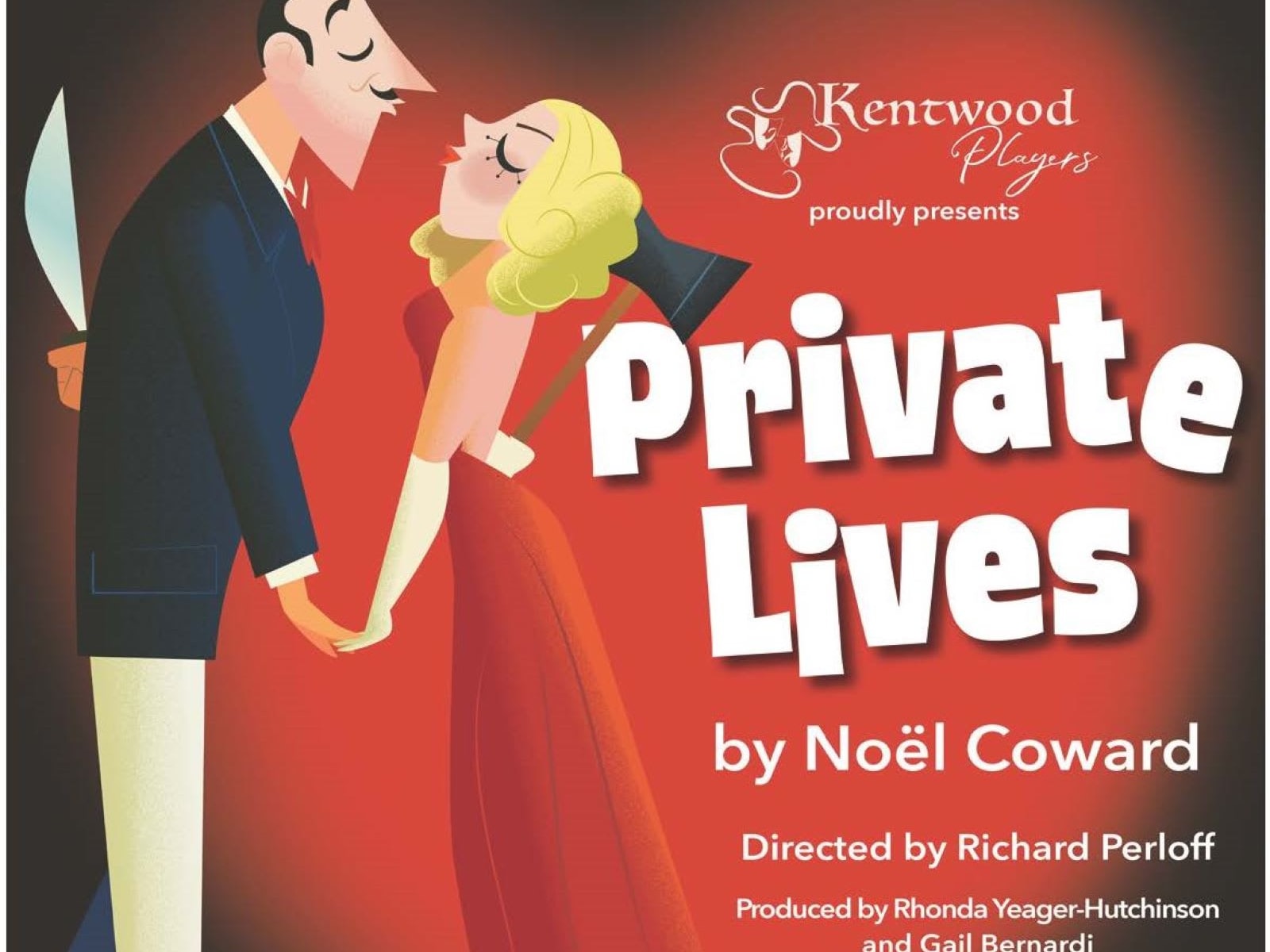

The Plot That Shouldn't Work (But Does)

The setup is almost a joke in itself. Elyot and Amanda, a divorced couple who had a notoriously volatile marriage, both show up at the same hotel in Deauville, France. They are both on their honeymoons with new, much more "sensible" spouses. Sibyl is Elyot’s new bride; Victor is Amanda’s new husband. They are boring. They are safe. They are exactly what you marry when you’re trying to recover from a person like Elyot or Amanda.

Then, the "balcony scene."

They realize they are in adjacent suites. They see each other. Instead of running away, they ditch their new spouses and run off to Paris together to resume their chaotic, beautiful, violent romance. It’s absurd. It’s romantic. It’s a total train wreck.

Why we still care about Elyot and Amanda

Most plays from 1930 feel like museum pieces. They’re dusty. They require a lot of historical context to understand why they were scandalous. Private Lives by Noel Coward doesn't have that problem. If you’ve ever had a "situationship" or an ex you just can't quit, you get this play.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Coward explores the idea that some people are just chemically incompatible with the rest of society but perfectly matched in their own private madness. They have a code word: "Sollocks." Whenever they start fighting too much, one of them says "Sollocks," and they have to be quiet for two minutes. It never works for long. The violence in the play—both verbal and physical—was shocking in 1930. It’s still a bit jarring today. They literally end Act II rolling around on the floor, smashing records over each other's heads.

The Secret Language of Noel Coward

There is a specific "Cowardian" rhythm. It’s fast. If you’re an actor and you try to put too much emotion into it, you kill the comedy. Coward himself famously told actors to "just say the lines and don't trip over the furniture."

He pioneered the use of "stichomythia"—that’s just a fancy word for rapid-fire dialogue where characters finish each other's sentences or throw one-word retorts back and forth. It creates a musicality. You don't just watch a Coward play; you listen to it like a jazz performance.

- The Subtext: In the famous "cheap music" scene, Amanda remarks, "Extraordinary how potent cheap music is." She isn't talking about the song. She’s talking about the memory of their marriage. She's talking about regret.

- The Cynicism: Coward didn't believe in the "happily ever after" of the Victorian era. He lived through the aftermath of WWI. He saw a world that was fractured. His characters reflect that—they are hedonistic because they don't really believe in the future.

- The Mirror Effect: Sibyl and Victor (the "new" spouses) aren't just plot devices. They represent "normal" society. By the end of the play, even they are screaming at each other. Coward is basically saying that the chaos of Elyot and Amanda is infectious. No one is truly "civilized."

Why "Private Lives" Almost Didn't Pass the Censors

In 1930, the Lord Chamberlain’s Office in the UK had to approve every play before it could be performed. They were the morality police. They hated Private Lives by Noel Coward.

The problem wasn't the swearing—there wasn't much. It was the "flippancy." The idea that two people could abandon their legal spouses and run off for a weekend of adultery and fighting, and that the audience might actually root for them, was considered dangerous to the fabric of society. Coward actually had to meet with the Censor and act out the play in his office to prove it wasn't "indecent." He argued that the characters were punished by their own temperaments, which was a clever way of saying they were miserable enough to satisfy the moralists.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

The play opened at the Phoenix Theatre in London. It was an instant smash. It then went to Broadway and did the exact same thing. It made Coward the highest-earning author in the world at the time.

Modern Productions and the Gender Flip

Because the play is so lean—only five characters and two main locations—it gets revived constantly. Everyone has done it. Laurence Olivier, Maggie Smith, Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Alan Rickman, Kim Cattrall.

But does it hold up in the 2020s?

Some critics argue that the physical fight at the end of Act II is problematic now. In 1930, a man and a woman hitting each other was played for "slapstick." Today, we see it through the lens of domestic abuse. However, the best productions (like the 2010 Broadway revival or the more recent London runs) lean into the ugliness. They don't make it pretty. They show that Elyot and Amanda are monsters. But they are charismatic monsters.

Recently, some directors have experimented with gender-blind casting or making the couples same-sex. Interestingly, the dialogue barely needs to change. The dynamic of "I love you but I want to kill you" is universal. It doesn't belong to any one gender or sexual orientation. Coward, who was a gay man living in a time when he had to remain closeted, likely wrote a lot of his own "outsider" perspective into these characters. They don't fit into the world's boxes.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

What You Get Wrong About the "Stiff Upper Lip"

A big mistake people make when reading or watching Private Lives by Noel Coward is thinking it’s about "posh" people being "posh."

It’s not.

It’s about the failure of being posh. It’s about what happens when the champagne runs out and you realize you’re still the same insecure, jealous, bored person you were before you bought the fancy silk robe.

Elyot says, "Let’s be superficial and silly, and throw things at each other." That’s a defense mechanism. He’s terrified of being serious because being serious means admitting how much he’s hurting. If you approach the play as just a series of witty quips, you miss the tragedy. It’s a tragedy wrapped in a tuxedo.

Actionable Insights for Theater Lovers and Writers

If you’re looking to dive deeper into Coward’s world or perhaps write something with this kind of snap, here is what you should actually do:

- Watch the 1931 Film: It’s not as good as the stage play, but it features Norma Shearer and Robert Montgomery. It gives you a sense of how the rhythm was originally intended.

- Read the Script Aloud: If you’re a writer, try reading the "balcony scene" out loud with a friend. Notice how the sentences get shorter as the tension rises. It’s a masterclass in pacing.

- Focus on the Props: Coward used objects—cigarettes, cocktails, record players—to give actors something to do with their hands. It makes the dialogue feel natural rather than "theatrical."

- Look for the "Sollocks" Moments: In your own relationships or writing, identify those "code words" that try (and fail) to stop a conflict. It’s a profound psychological insight into how people communicate.

The reality of Private Lives by Noel Coward is that it doesn't offer a solution. It doesn't tell you how to have a healthy marriage. It just holds up a mirror to the most volatile parts of our hearts and asks us to laugh at the reflection. It’s cynical, it’s cruel, and it’s probably the most honest thing ever written about the "honeymoon phase."

Next time you’re flipping through streaming services or looking for a play to see, check if there’s a local production. Even a bad production of Private Lives is usually better than a good production of almost anything else. The bones of the script are just too strong to break.