Jane Austen probably didn’t imagine Elizabeth Bennet wearing a pink tracksuit or Mr. Darcy brooding by a swimming pool in Provo, Utah. But that’s exactly what happened in 2003. When we talk about Austen adaptations, the conversation usually circles around Colin Firth’s lake jump or Keira Knightley’s wind-swept pouting. We rarely talk about Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy. Honestly, it’s a movie that feels like a fever dream from the early 2000s, yet it remains a fascinating case study in how to translate 19th-century social rigidness into modern religious subcultures.

It was a bold move. Taking a beloved literary masterpiece and dropping it into the middle of a Brigham Young University (BYU) setting sounds like a recipe for a disaster. Or a cult classic.

Most people don’t realize that this film wasn't just a generic rom-com with a Jane Austen sticker slapped on the front. It was a specific attempt to map the marriage-obsessed culture of the Regency era onto the high-pressure "marriage-culture" of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). In Austen’s world, if you didn't marry well, you were socially dead. In the world of Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy, if you’re a single woman over 22 at BYU, you’re basically an "old maid." The stakes are surprisingly similar.

What Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy Actually Got Right

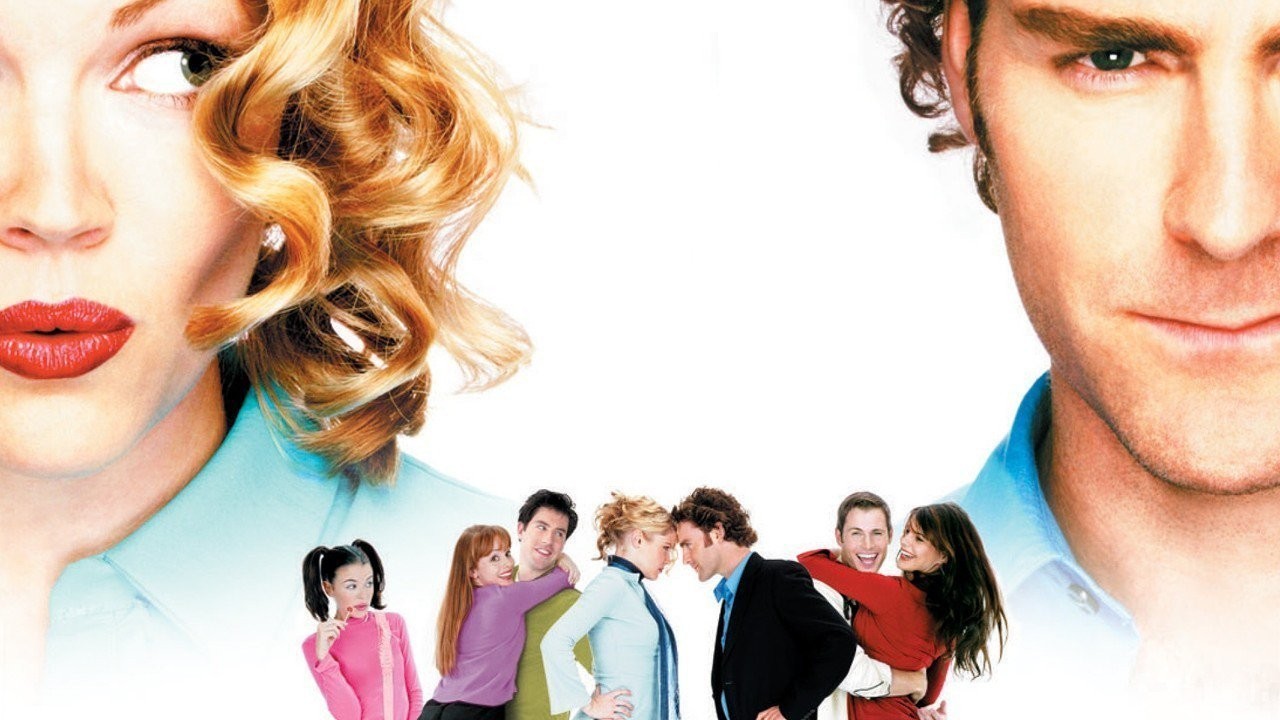

Elizabeth Bennet became Elizabeth "Lizzie" Ashford, an aspiring writer working at a bookstore. Darcy became Will Darcy, a high-brow businessman. The core of the story remains: two people who think they’re better than everyone else eventually realize they’re just better for each other.

What's wild is how well the "entail" translates. In the original book, the Bennet girls are in trouble because they can't inherit their father's estate. In the 2003 film, the pressure isn't about losing a house; it’s about the cultural expectation of the "eternal marriage." Director Andrew Black and screenwriter Anne K. Black leaned hard into the specificities of Utah life. We aren't talking about balls and assemblies here. We’re talking about pink foam parties and awkward double dates at cheap diners.

The film captures a very specific 2003 aesthetic. Think butterfly clips, chunky highlights, and those specific striped polos every guy seemed to wear. It’s a time capsule. For an Austen fan, seeing the "social hierarchy" of Meryton replaced by the social hierarchy of a college town is genuinely funny. You’ve got the "Lydia" character (Liddy) who is obsessed with finding a husband—any husband—and the "Jane" character who is just too pure for this world.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The Weird Connection Between Regency England and Modern Utah

Why does this work? Or, more accurately, why does it almost work?

Jane Austen’s novels are fundamentally about the economics of marriage. You marry for money, or you marry for love and hope the money follows. In Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy, the currency isn't just money; it's social standing within a tight-knit religious community. The "scandal" of Lydia running off with Wickham is replaced by Liddy running off to Las Vegas to get married by an Elvis impersonator. In both versions, the family's reputation is on the line.

Let’s look at the characters. Orlando Seale played Will Darcy. He wasn't playing a brooding British lord; he was playing a rich, somewhat snobbish guy who looked down on the "uncultured" nature of the local college kids. Kam Heskin’s Lizzie was sharp-tongued and stubborn. The chemistry was... well, it was G-rated. But that was the point.

One of the funniest pivots in the script is the "Lady Catherine de Bourgh" character. Instead of a terrifying noblewoman, we get a wealthy, overbearing aunt who controls the family’s business interests. It’s a clever way to keep the obstacle of social class alive in a country that pretends class doesn't exist.

Why the Critics Hated It (and Fans Didn't)

If you look at the Rotten Tomatoes score for Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy, it’s not pretty. Critics called it amateurish. They hated the low budget. They found the "inside jokes" about LDS culture confusing.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

But for the audience it was made for? It was a hit. It spoke a language that mainstream Hollywood didn't understand. It’s a "niche" film in the truest sense. It doesn't care if a guy in New York understands why a "Mormon Muffins" calendar is funny. It was made for people who grew up in that world.

Exploring the Production Reality of a Low-Budget Indie

This wasn't a big-studio production. It was an independent film, and you can see it in the lighting. Some scenes look like they were shot on a home camcorder. But there is a charm in that grit. It feels like a theater troupe decided to put on a movie.

- The Casting: Many of the actors were unknowns or regulars in the burgeoning "LDS Cinema" scene of the early 2000s.

- The Soundtrack: It’s a mix of upbeat pop-rock that feels incredibly dated now, but it perfectly captures the "Provo Mix" vibe of the era.

- The Humor: It relies heavily on slapstick. Think Jane Bennet getting a horrific cold or Mr. Collins (renamed Collins, a nerdy missionary-obsessed guy) being unintentionally creepy.

Hubbel Palmer’s performance as Collins is arguably the best part of the movie. He is painfully awkward. Every time he’s on screen, you want to crawl under your seat, which is exactly how Mr. Collins is supposed to make you feel. He captures that specific type of guy who thinks he’s a catch because he’s "doing all the right things," but has zero social awareness.

Does it Hold Up in 2026?

Looking back from 2026, the movie is a museum piece.

The technology is ancient. The fashion is a crime. But the themes? They’re still there. The struggle to find someone who actually likes you for your brain and not just your "potential" is a universal theme that Austen nailed 200 years ago. Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy just happens to put that struggle in a bookstore in Utah.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

It’s worth watching if you’re a completionist. If you’ve seen the 1995 BBC version and the 2005 Joe Wright version, you owe it to yourself to see the weird American cousin. It’s not "prestige" TV. It’s not "high art." It’s a quirky, low-budget experiment that proves Jane Austen’s plots are indestructible. You can put them anywhere—even in a pink foam party—and they still work.

Misconceptions About the Film

Some people think this is a "religious" movie meant to convert people. It’s really not. It’s a romantic comedy that happens to take place in a religious setting. It pokes a lot of fun at the culture it depicts. It mocks the "dating games" people play. It mocks the pressure to get married young.

Another misconception: that it’s a shot-for-shot remake. It’s a "loose" adaptation. Some characters are combined, some subplots are dropped. Wickham is now a guy named Jack Wickam who is a shady guy in the publishing world. It’s modernized in ways that make sense for the 2003 setting, even if those things feel old now.

Actionable Takeaways for Austen Fans

If you're planning to dive into this niche corner of the Austen-verse, keep these things in mind to actually enjoy the experience:

- Adjust your expectations for production value. This is an indie film from 2003. The audio quality can be spotty, and the cinematography is basic.

- Watch it as a cultural artifact. It’s a window into a very specific time and place. See it as a "Modernization Experiment" rather than a definitive version of the book.

- Look for the "Easter Eggs." The film is full of nods to the original text. Pay attention to the dialogue; some of the most famous lines from the book are hidden in the modern conversations.

- Compare it to Clueless or Bridget Jones. Those are also Austen adaptations (Emma and Pride and Prejudice respectively). Seeing how different directors handle the "modern" transition is a great way to understand what makes Austen's writing so timeless.

Ultimately, Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy isn't going to replace the classics. It's a side dish. A weird, slightly dated, surprisingly charming side dish. It reminds us that no matter where you are—Longbourn or Salt Lake City—first impressions are usually wrong, and your mom is probably trying too hard to set you up with someone you hate.

To get the most out of your viewing, try to find the "Special Edition" DVD if you can. The behind-the-scenes features explain a lot of the choices the filmmakers made regarding the adaptation of 19th-century manners to 21st-century social codes. It’s a masterclass in low-budget adaptation, even if the result is more "guilty pleasure" than "Academy Award contender."