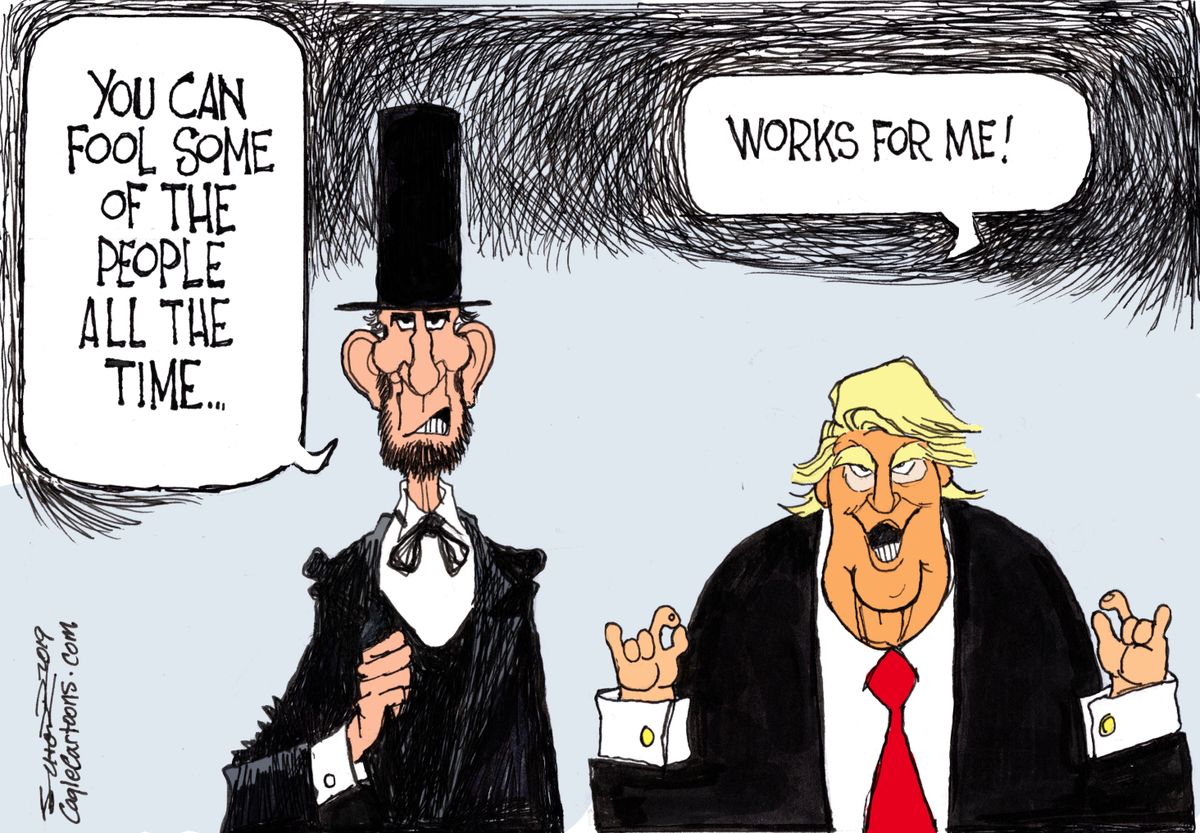

He’s a god now. If you walk into the Lincoln Memorial, you’re looking at a marble deity, a stoic "Great Emancipator" with perfect posture and a look of eternal wisdom. But if you hopped into a time machine and flipped through a newspaper in 1862, you wouldn't see a god. You’d see a monster. Or a buffoon. Or a spindly, rail-splitting backwoodsman who was way out of his depth. Political cartoons on Abraham Lincoln were the memes of the 19th century, and they were brutal.

Honestly, it’s shocking. We’re used to political satire being a bit edgy, but the Victorian era had zero chill when it came to Honest Abe.

The Ugly Side of the Illustrated Press

Modern politics feels toxic, sure. But Lincoln dealt with a level of visual vitriol that would make a Twitter troll blush. You have to remember that during the mid-1800s, literacy rates were high, but visual storytelling was king. Publications like Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and the British magazine Punch were the gatekeepers of public opinion.

Lincoln was a cartoonist’s dream—and nightmare. He was 6'4", gangly, with a face that even he joked was "homely." Cartoonists leaned into this. They didn't just draw him; they dissected him. They gave him oversized feet, hair that looked like a bird’s nest, and limbs that seemed to be made of wet noodles.

In the North, he was often depicted as a well-meaning but incompetent "rail-splitter." In the South, and even in some London papers, he was drawn as a "Beelzebub" or a tyrant. One of the most famous examples, titled "The Rail Candidate," shows Lincoln being carried on a rail by a Black man and an abolitionist, suggesting he was a puppet for radical interests. It wasn't about policy. It was about character assassination.

The British Influence and Punch Magazine

Most people forget that the British were obsessed with the American Civil War. Punch magazine, the gold standard of satire at the time, was relentless. Their lead cartoonist, John Tenniel—the same guy who illustrated Alice in Wonderland—portrayed Lincoln as a cunning, shifty figure.

In one 1862 cartoon, "The Federal Phoenix," Lincoln is drawn as a bird rising from the ashes of the Constitution. It sounds cool, but the intent was the opposite. It was a critique of his suspension of habeas corpus. The British elite were skeptical of democracy, and they used Lincoln as the poster child for why it supposedly wouldn't work.

But then, something shifted.

📖 Related: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

When Lincoln was assassinated, Tenniel and Punch did a complete 180. They published a poem and an illustration titled "Britannia Sympathises with Columbia," showing a repentant Britain laying a wreath on Lincoln’s bier. It’s one of the few times in history a satirical publication basically admitted, "My bad, we got this guy totally wrong."

Why the "Rail-Splitter" Image Stuck

You’ve probably seen the cartoons of Lincoln swinging an axe. This wasn't accidental. It was a branding war.

His campaign managers, particularly during the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago, leaned into the "Rail-Splitter" persona to make him feel like a man of the people. They wanted him to contrast with the "fancy" East Coast elites.

Cartoonists took that ball and ran with it.

- Pro-Lincoln cartoons showed him using his "rail" to bridge the gap between states.

- Anti-Lincoln cartoons showed him using the rail to beat the Constitution into submission.

It’s a classic example of how a single visual metaphor can be weaponized by both sides. One person's "hard-working pioneer" is another person's "uncivilized brute."

The Emancipation Proclamation as a Turning Point

Everything changed in 1863. Before the Proclamation, cartoons focused on Lincoln’s inability to win the war. They called him "The Illinois Ape."

After Jan. 1, 1863, the imagery got much darker. In the South, Adalbert Volck, a dentist from Baltimore who moonlighted as a Confederate propagandist, produced some of the most haunting political cartoons on Abraham Lincoln. In one, Lincoln is at a desk, his foot resting on the Constitution, while a devil holds his inkwell.

👉 See also: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

It wasn't just "mean." it was a visual argument that Lincoln was literally demonic for upending the social order of the South.

The "Columbia" Metaphor

If you look at enough of these old prints, you’ll notice a recurring character: Columbia. She was the female personification of the United States, usually wearing a Phrygian cap and flowing robes.

In many cartoons, Lincoln is depicted as a clumsy suitor or a failing doctor trying to "save" Columbia. In "The Doctors Perplexed," Lincoln is shown trying to treat a sick Columbia with "Draft" medicine (the military conscription), while his political rivals offer "Peace" pills.

These cartoons show the immense pressure he was under. He wasn't the confident leader we see on the five-dollar bill. In the eyes of his contemporaries, he was a guy trying a dozen different "cures" for a dying country, and most people thought he was killing the patient.

It Wasn't All Heavy

Lincoln actually loved some of these. He was known to have a self-deprecating sense of humor. He once said that if he were two-faced, he wouldn't be wearing the one he had.

Some cartoons were genuinely funny in a "dad joke" sort of way. There’s one where he’s trying to catch a "Confederate pig" that keeps slipping through his fingers. It highlighted the frustration of the Union’s early military failures without necessarily calling him a tyrant.

How to Analyze These for Yourself

If you're looking at a Lincoln cartoon and trying to figure out what’s actually going on, look for three things:

✨ Don't miss: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

- The Height Factor: If he’s drawn exceptionally tall and awkward, it’s usually a Northern "backwoodsman" critique.

- The Animal Traits: If he has ape-like features, you’re likely looking at Copperhead (anti-war Democrat) or Southern propaganda.

- The Background Props: Look for the Constitution. Is it being protected, or is it torn on the floor? That tells you the artist's stance on his executive overreach.

The reality is that political cartoons on Abraham Lincoln didn't just reflect public opinion; they shaped it. They took a complicated, deeply conflicted man and boiled him down into a series of easily digestible—and often hateful—caricatures.

What We Can Learn Today

We often think we live in uniquely divisive times. We don't.

Looking at these 160-year-old drawings proves that the American experiment has always been loud, messy, and visually violent. Lincoln survived the worst the press could throw at him, and eventually, the cartoons caught up to his greatness. It took a tragedy for the artists to stop drawing him as a monster and start drawing him as a martyr.

If you want to see these for yourself, the Library of Congress has a massive digital archive. You can spend hours zooming in on the tiny details in these lithographs. It’s a trip. You’ll see the same arguments we have today—about presidential power, civil rights, and the media—playing out in ink and paper.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs

To truly understand this era, you have to go beyond the textbooks.

- Visit the Library of Congress Online: Search for the "Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana." It’s the motherlode of primary sources.

- Compare Punch vs. Harper’s: Find a single event, like the Battle of Gettysburg, and look at how the British press drew Lincoln versus how the New York press did. The difference in "vibe" is wild.

- Check out Thomas Nast: He’s the father of American political cartoons. While he’s more famous for his work on Boss Tweed and Santa Claus, his depictions of Lincoln and the Union cause are foundational to American visual history.

- Look for "Copperhead" Cartoons: These were the Northern Democrats who wanted peace at any cost. Their cartoons are some of the most vicious because they felt Lincoln was destroying the North to save the Union.

Understanding these images gives you a superpower: the ability to see through the "myth" of the historical figure and see the actual man who had to wake up every morning and read about how much people hated him. It makes his eventual success feel much more human.

The next time you see a political meme on your phone, remember that Lincoln was dealing with the exact same thing in 1864. The only difference is that back then, they had to carve the "meme" into a woodblock before they could print it.