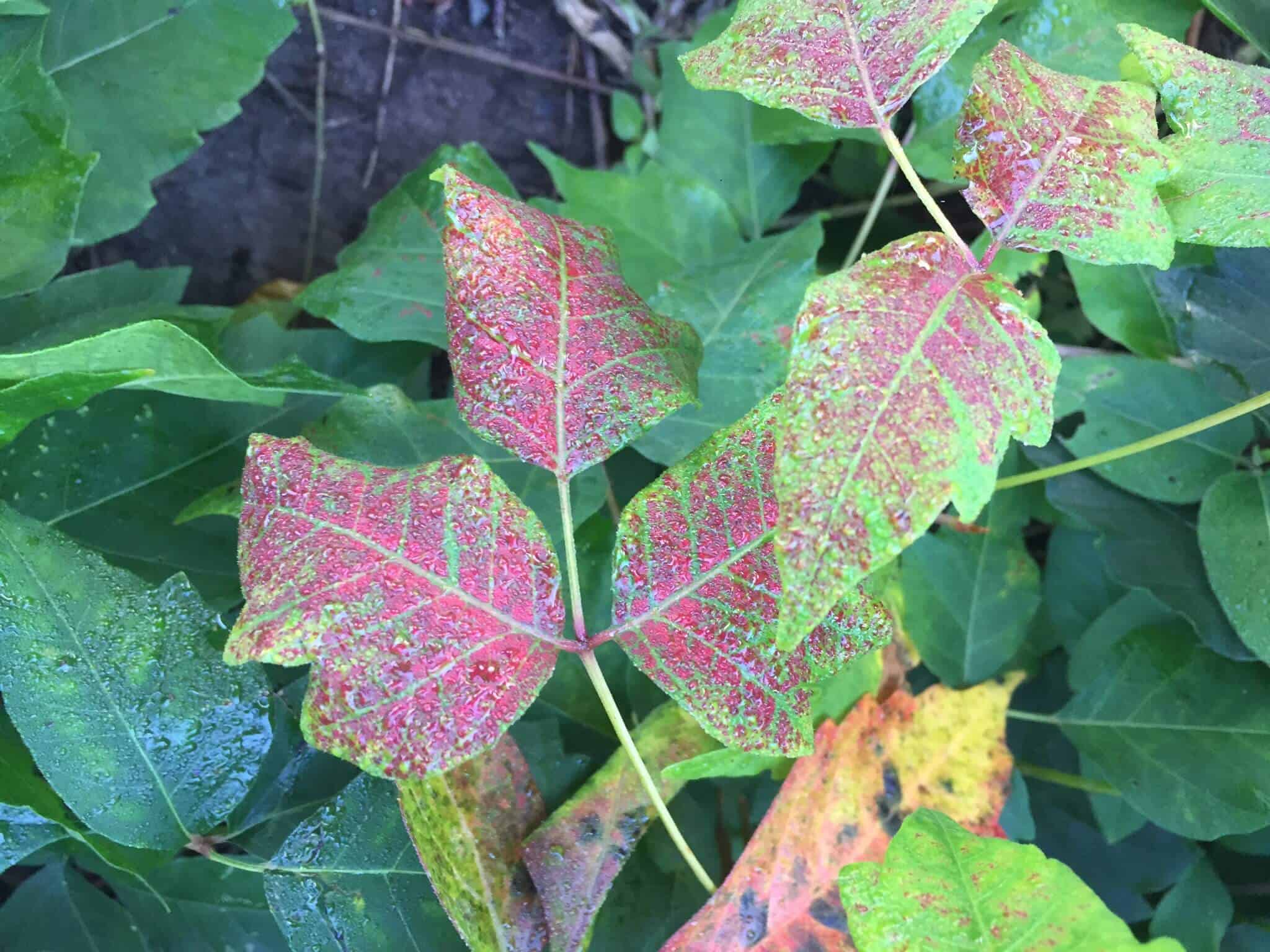

You’re walking through the woods on a crisp October afternoon, the smell of damp earth and decaying leaves hitting just right. The trees are putting on a show. You see a vine wrapped around an oak tree, sporting some of the most beautiful, vibrant crimson leaves you’ve ever seen. You might even be tempted to snap a photo or, heaven forbid, tuck a few into a centerpiece for your dining room table. Don't do it. Seriously. That stunning red foliage is poison ivy in the fall, and it’s arguably more deceptive now than it was back in June.

Most people let their guard down once the first frost hits. There’s this weird, collective myth that plants just "turn off" when the temperature drops. But Toxicodendron radicans—the botanical name for the bane of your existence—doesn't work like that. The plant might be preparing for dormancy, but the chemical that causes that blistering, itchy nightmare is very much awake.

The Chemistry of the Crimson Leaf

The reason poison ivy in the fall looks so different is basically a survival tactic. As the days get shorter, the plant stops producing chlorophyll. When the green fades, it reveals anthocyanins—those red and orange pigments. It’s a literal red flag, but because we associate autumn colors with "cozy" vibes, we forget that the plant is still loaded with urushiol.

Urushiol is an oily resin. It's sticky. It's stubborn. It’s also incredibly potent. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, a microscopic amount—less than a grain of salt—is enough to give 80% of the population a rash. In the fall, the leaves become brittle. They break easily. When they tear, they release that oil more readily than the flexible, waxy leaves of mid-summer.

Here is the kicker: the oil doesn't just stay on the plant. If you’re hiking and you brush against a dry, red leaf, that oil hitches a ride on your flannel shirt, your dog's fur, or your hiking boots. And it stays there. Urushiol is chemically stable. Researchers have found that urushiol can remain active on surfaces for years. You could touch a pair of gardening gloves you used in November three years later and still get a breakout.

Why the "Hairy Vine" is Your Worst Enemy Now

Sometimes the leaves have already fallen off. You're left with a naked vine climbing a tree. It looks like a harmless, fuzzy rope. It’s not. In the fall and winter, those "hairs" (which are actually aerial roots) are saturated with urushiol. Biologists often point out that the concentration of the toxin can be even more dense in the woody parts of the plant during the dormant season.

💡 You might also like: 5 feet 8 inches in cm: Why This Specific Height Tricky to Calculate Exactly

If you're clearing brush in late October, you might think you're safe because the "three leaves" are gone. You aren't. Honestly, "leaves of three, let it be" is a great rule for kids, but for adults, the real rule should be "if it’s a hairy vine, leave it behind."

The Burning Mistake: A Warning for Leaf Burners

This is where things get genuinely dangerous. Every year, someone decides to clear out the "dead" brush at the edge of their property and throw it on a bonfire. If poison ivy in the fall ends up in that pile, you aren't just cleaning up your yard—you're creating a toxic aerosol.

When urushiol burns, it doesn't disappear. It attaches to the smoke particles. If you inhale that smoke, the rash doesn't stay on your skin. It goes into your lungs. This is a medical emergency. Doctors at institutions like the Mayo Clinic warn that pulmonary exposure to urushiol can cause severe respiratory distress, extreme swelling of the throat, and systemic internal reactions. If you see a vine with white, waxy berries—a classic marker of autumn poison ivy—keep it far away from any flame.

Identification Without the Green

So, how do you actually spot this stuff when the forest floor is a chaotic mess of brown and gold? You have to look at the structure.

- The Berries: Look for small, off-white, or grayish berries. They look a bit like tiny, shriveled pumpkins. Birds eat them (they’re immune), but for you, they are a giant "keep out" sign.

- The Luster: Even when red or yellow, poison ivy leaves often have a slight waxy sheen compared to the matte finish of a raspberry bush or Virginia Creeper.

- The Asymmetry: If you look closely at the two side leaves, they often look like mittens with a single "thumb" sticking out. The middle leaf usually has a longer stalk than the two side ones.

- The Vine: Look for those black, stringy "hairs" on the bark of trees.

Virginia Creeper is the most common lookalike. People mix them up constantly. Virginia Creeper usually has five leaves and turns a similar brilliant red. But sometimes a young Virginia Creeper only shows three leaves. When in doubt, just don't touch it. It’s not worth the two weeks of Prednisone and Calamine lotion.

📖 Related: 2025 Year of What: Why the Wood Snake and Quantum Science are Running the Show

The "Fallen Leaf" Trap

You’re raking the yard. You’re wearing shorts because it’s a weirdly warm 70-degree day in November. You grab a handful of leaves to stuff into a bag. Inside that pile of maple and oak leaves is one stray, red poison ivy leaf.

That’s all it takes.

Because the leaves are dying, they are more "leaky." The cellular structure is breaking down, making the oil more accessible. It’s not tucked away in the veins anymore; it’s basically smeared on the surface. Also, remember that urushiol is an allergen, not a mechanical irritant. Your body’s immune system reacts to the protein bond the oil creates with your skin cells. In the fall, your skin might be drier, which can sometimes lead to micro-cracks that let the oil penetrate even deeper.

What to do if you messed up

If you realize you’ve touched it, you have a very narrow window. We’re talking 10 to 30 minutes.

You need a degreaser. Standard hand soap is okay, but something like Dawn dish soap or a specialized wash like Tecnu is better. The goal is to strip the oil off. Think of it like axle grease. If you just rinse with water, you’re just spreading the grease around. You need to scrub with a washcloth (which you then throw straight into the laundry) to physically lift the resin.

👉 See also: 10am PST to Arizona Time: Why It’s Usually the Same and Why It’s Not

And for the love of everything, wash your tools. If your rake or your loppers touched that red vine, they are now "hot." Use rubbing alcohol to wipe down the handles and the blades.

Strategic Prevention for the Late Season

The most important thing to remember is that "dead" does not mean "safe." If you are doing fall landscaping, wear long sleeves and tuck your pants into your socks. It looks dorky. It also keeps you out of the urgent care clinic.

If you have a massive infestation, late fall is actually a decent time to treat it with a systemic herbicide because the plant is pulling nutrients (and the poison) down into the roots for winter. However, you still have to deal with the physical vine. Never pull it with your bare hands. Use heavy-duty disposable gloves or thick rubber ones that you can wash thoroughly afterward.

Actionable Next Steps for Fall Yard Work:

- Survey First: Before you start raking or clearing brush, walk your property line specifically looking for red, three-leafed clusters or hairy vines.

- Barrier Cream: If you know you're going into "hot" zones, use a bentoquatam-based barrier cream (like Ivy Block). It acts like a shield for your skin.

- The Cold Wash: If you think you've been exposed, use cold water to rinse. Hot water opens your pores and can actually invite the urushiol in.

- Pet Management: If your dog runs through the brush, they need a bath immediately. Use gloves while washing them. Their fur protects them, but it turns them into a walking urushiol sponge that will transfer the oil to your couch and your bedsheets.

- Ditch the Shoes: Keep your outdoor work shoes in the garage. Don't kick them off with your bare hands. Use a brush and soapy water to clean the soles and laces.

Poison ivy in the fall is a master of disguise. It’s the "pretty" version of a nasty foe. Treat every red vine with extreme suspicion and you'll make it to winter without the itch.