Walk down Orange Street in Brooklyn Heights and you'll hit a massive brick building that looks more like a sturdy New England meeting house than a high-cathedral masterpiece. It’s Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims Brooklyn. If these walls could actually talk, they wouldn't just whisper; they’d probably shout about the end of the world, the birth of modern human rights, and the time Abraham Lincoln sat in pew 69 just to see what all the fuss was about.

Honestly, it’s easy to walk past it. People do every day on their way to the Promenade. But you shouldn't.

This isn't just a place for Sunday service. It was the "Grand Central Depot" of the Underground Railroad. It was where Henry Ward Beecher—basically the first American celebrity—preached to thousands of people who were so desperate to hear him they’d wait in line for hours. Today, it’s a living museum of American grit.

The Beecher Phenomenon and the "Grand Central Depot"

Henry Ward Beecher was kind of a big deal. Imagine a mix of a rock star, a politician, and a preacher, but with even more social influence. When he took the pulpit at Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims Brooklyn in 1847, he didn't just talk about theology. He talked about the burning moral crisis of the era: slavery.

He was bold. Sometimes dangerously so.

He famously held "mock auctions" right there in the church. He’d bring a young enslaved woman onto the platform and ask the congregation to bid for her freedom. It was high drama. It was shocking. It worked. People would throw their jewelry and gold coins into the collection plates to buy someone's life back from the brink of being sold South. Critics called it "Beecher’s Bibles," referring to the Sharps rifles he helped ship to abolitionists in Kansas. He wasn't just praying for change; he was funding the fight.

✨ Don't miss: How Long Ago Did the Titanic Sink? The Real Timeline of History's Most Famous Shipwreck

The basement of this church served as a literal sanctuary. It’s one of the few documented sites in New York City where we know for a fact that people escaping slavery were hidden before being moved further north or toward Canada.

That One Time Lincoln Showed Up

In February 1860, a relatively unknown lawyer from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln came to New York. He was supposed to speak at Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims Brooklyn first, but the venue got switched to Cooper Union at the last minute. Still, Lincoln didn't skip the church visit. He sat in the pews on Sunday morning. You can still see the spot today. It’s marked with a small plaque.

Historians often argue that the "Cooper Union Address" won Lincoln the presidency. If that's true, then the Brooklyn crowd that hosted him and the political energy of Plymouth Church were the literal fuel for his campaign. Without this specific Brooklyn community, American history might look completely different.

The Architecture of Radical Simplicity

Most churches built in the mid-1800s were trying to outdo each other with Gothic spires and ornate carvings. Plymouth went the other way. It’s an Italianate style, sure, but it’s incredibly plain. That was intentional.

The congregation didn't want a "temple." They wanted a "meeting house."

🔗 Read more: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

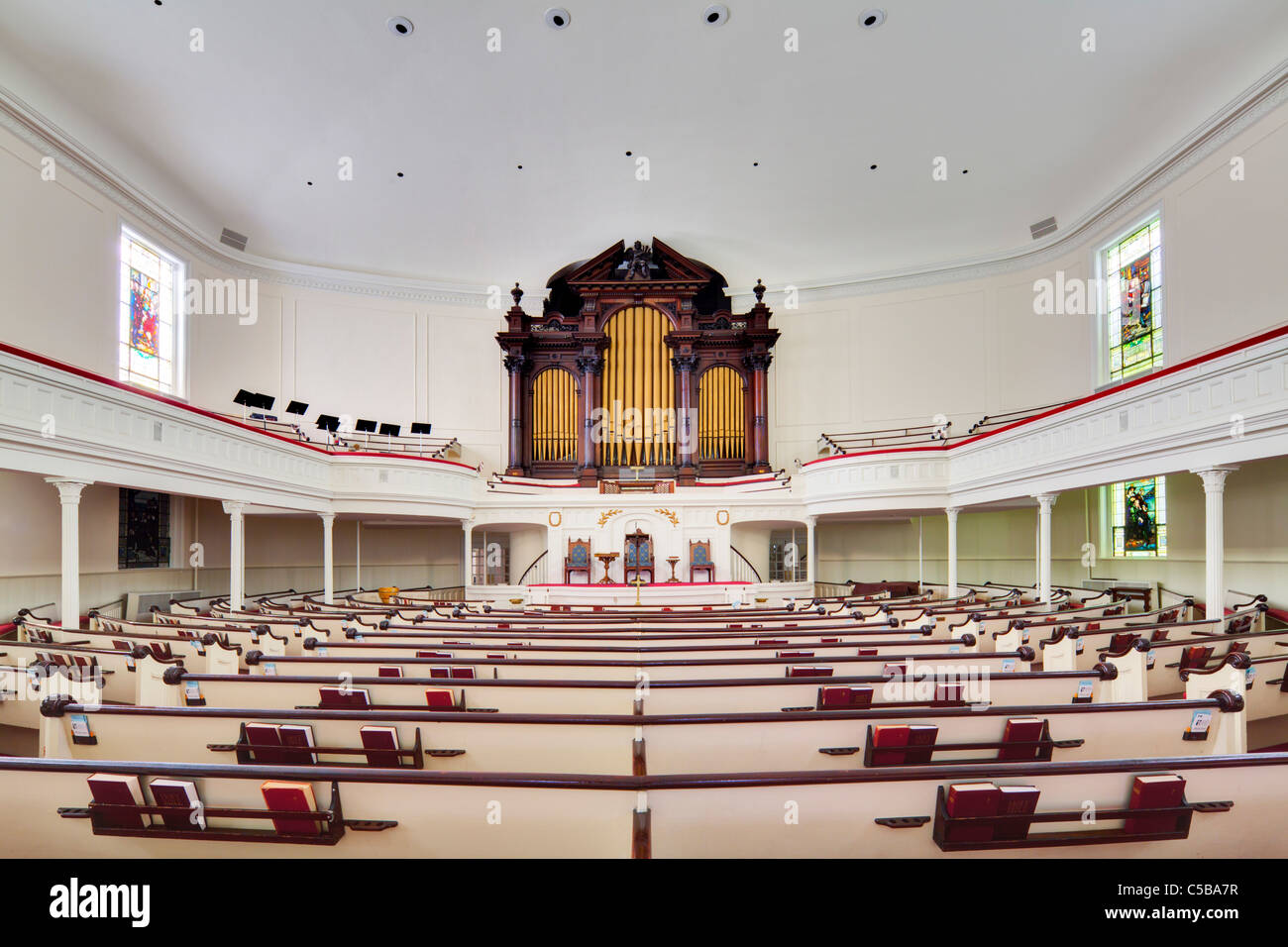

Inside, the sanctuary is designed like a theater. There are no massive stone pillars blocking your view. It was built so every single person could see and hear the speaker. This reflects the Congregationalist belief that the people are the church, not the building or the hierarchy.

- The Windows: You won't find traditional biblical scenes here. Instead, the stained-glass windows depict the history of religious liberty. Think Pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock or the signing of the Magna Carta.

- The Organ: It has been rebuilt and restored, but it remains one of the most powerful instruments in the city.

- The Garden: Outside, there’s a statue of Beecher by Gutzon Borglum. Yes, the same guy who carved Mount Rushmore.

Why People Get This Place Wrong

Some folks think Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims Brooklyn is just a relic for history buffs. That’s a mistake. It’s easy to look at the brick and see 1850, but the church has constantly evolved. It merged with the Church of the Pilgrims in 1934, which is why the name is such a mouthful.

The merge brought together two different styles of Brooklyn Heights worship—the radical abolitionism of Plymouth and the more traditional "Pilgrims" crowd.

There's also a misconception that abolitionism was universally popular in Brooklyn back then. It really wasn't. Brooklyn was a major port city with huge financial ties to the cotton trade. Beecher and his congregation were often putting their businesses and reputations on the line by being so vocal. It was a pocket of resistance in a city that was very conflicted about the Civil War.

How to Actually Experience It Today

If you’re just visiting, don't just stare at the front door. The church offers tours, often led by the church historian or dedicated volunteers who know where the literal bodies are buried (or at least where the secret tunnels were).

💡 You might also like: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

- Check the Tour Schedule: They don't happen every day. You usually need to book ahead or catch a session after the Sunday service.

- Look for the Piece of Plymouth Rock: Seriously. There is a piece of the actual Plymouth Rock embedded in the wall of the hallway. It was brought down from Massachusetts as a symbolic link to their namesake.

- Walk the Grounds: The courtyard is one of the most peaceful spots in all of Brooklyn Heights. It feels like a time machine.

- Attend a Concert: Because the acoustics were designed for 19th-century oratory, it’s one of the best places in New York to hear choral music or a pipe organ.

Actionable Insights for History Seekers

If you're planning a visit to Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims Brooklyn, pair it with a walk through the rest of the neighborhood. Brooklyn Heights was the first landmarked district in New York City for a reason.

Start at the church, then head three blocks over to the Brooklyn Heights Promenade. From there, you can see the Manhattan skyline—the same view (minus the skyscrapers) that the abolitionists would have looked at while planning their next move.

Check the church's official website for their "History Ministry" events. They often host lectures that go deeper into the specific biographies of the men and women who used the church as a stop on the Underground Railroad. It turns the abstract concept of "history" into something you can actually touch.

The Real Legacy

It’s about the idea that a community can be a force for massive social change. You don't need a cathedral. You need a room where people are willing to listen to uncomfortable truths.

That’s what happened in this corner of Brooklyn. It wasn't just about Sunday morning; it was about what happened the other six days of the week. Whether you're religious or not, the sheer weight of the activism that started here is staggering. It’s a reminder that Brooklyn has always been a place where people come to change the world.

To make the most of your trip, visit the church on a Sunday morning or during a scheduled weekday tour. Wear comfortable shoes for the cobblestone streets nearby. Most importantly, take a moment in the sanctuary to sit in silence. The acoustics are so good you can almost hear the echoes of the 1860s.

After your visit, walk down to the New York Transit Museum in Downtown Brooklyn or the Brooklyn Historical Society to see how the rest of the borough grew up around this landmark. This gives you the full context of how a single church helped shape the identity of the "City of Churches."