Search for it. Go ahead. If you’ve just received a skin cancer diagnosis, your first instinct is probably to hit Google Images and type in pictures of wide excision for melanoma. What you’ll see is... a lot. Deep red craters. Stitched-up lines that look like a football. Gauze soaked in yellow antiseptic. It looks like a shark bite. Honestly, it’s terrifying if you don’t have the context of how human skin actually heals.

Most people see those raw, immediate post-op photos and panic. They think their arm, leg, or face is going to be permanently disfigured. But those photos are just a single frame in a very long movie. A wide local excision (WLE) is the gold standard for treating melanoma because it saves lives by ensuring "clear margins." It’s a surgical necessity, not a cosmetic choice, though the two worlds collide more often than you'd think.

The Brutal Geometry of the "Safety Margin"

Why is the hole so much bigger than the mole? That’s the question everyone asks when they see pictures of wide excision for melanoma. If you have a melanoma that is only 5 millimeters wide, your surgeon isn’t just taking that 5mm. They are taking a "margin" of healthy-looking skin around it.

According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, those margins are strictly defined. For a melanoma in situ (stage 0), the surgeon usually takes 5mm of clear skin. For a lesion thicker than 2mm, that margin jumps to 2 centimeters.

Do the math.

A 1cm melanoma with a 2cm margin on each side results in a 5cm defect. On a calf or a forearm, 5 centimeters is massive. It’s the difference between a band-aid and a pressure dressing. The reason surgeons do this—and why the pictures look so aggressive—is because melanoma cells are notorious for "microsatellites." These are tiny clusters of cancer cells that break off from the main tumor and hide in the surrounding tissue. If the surgeon misses them, the cancer comes back. Hard.

What You Are Actually Seeing in Those Photos

When you scroll through medical journals or patient blogs, you’re seeing different stages of the "insult" to the tissue.

🔗 Read more: Exercises to Get Big Boobs: What Actually Works and the Anatomy Most People Ignore

First, there’s the "immediate post-excision" shot. This is the one that goes viral on Reddit or health forums. The skin is gone. You might see the yellow of subcutaneous fat or even the white of the fascia covering the muscle. It looks like a hole. It's supposed to.

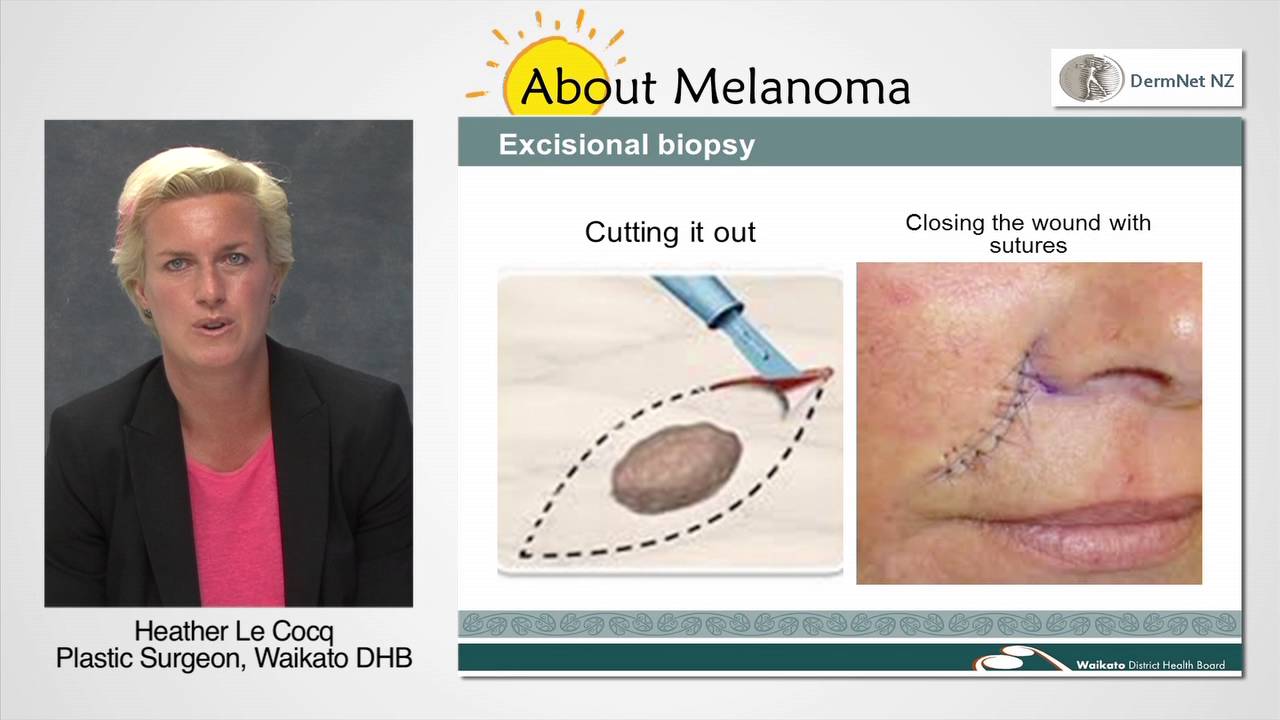

Then come the "closure" pictures. Surgeons don't usually leave a round hole. They turn it into an ellipse—a football shape. Why? Because you can’t easily pull the edges of a circle together without the skin puckering at the ends (surgeons call these "dog ears"). By cutting a long oval, they can pull the skin taut and create a flat, clean line. This is why a small round mole results in a three-inch-long scar.

The Reconstruction Factor

Sometimes a simple stitch-up isn't enough. If you’re looking at pictures of wide excision for melanoma on the shin or the scalp, where the skin is tight, you might see "flaps" or "grafts."

- Skin Grafts: This is where they take skin from somewhere else (like your thigh) and staple it over the hole. In the beginning, these look like a different-colored patch of leather. It’s weird.

- Rotation Flaps: This is some high-level geometry. The surgeon cuts a "puzzle piece" of skin nearby and slides it over the wound. The scar looks like a Z or a spiral. It's fascinating, but in early photos, it looks like a roadmap of stitches.

The "Scary" Phase vs. The "Six Months Later" Reality

Let’s talk about the inflammatory phase. About 48 to 72 hours after the surgery, the site is going to look its worst. It’ll be bruised. Purple, green, and sickly yellow. The edges of the incision might look angry and red.

Most pictures of wide excision for melanoma taken during this week lead patients to believe they have an infection. In reality, it’s just the body’s massive immune response. Blood is rushing to the area to start the repair work.

If you look at photos from six months or a year post-op, the story changes completely. The body is an incredible machine. That angry red line fades to pink, then eventually to a silvery-white that's often flush with the skin. Laser treatments and silicone scarring sheets have become incredibly effective at minimizing the long-term visual impact.

💡 You might also like: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

Realities of the Procedure Nobody Mentions

People focus on the scar, but they forget about the "dent."

Because the surgeon has to take the full thickness of the skin down to the fat or muscle, there is often a physical depression in the limb. If you look at profile-view pictures of wide excision for melanoma, you’ll notice the contour of the body changes. For some, this is more distressing than the scar itself.

Then there’s the numbness. By cutting that wide margin, the surgeon is inevitably severing small cutaneous nerves. The area around the scar might feel like "dead skin" or tingle for months. Sometimes the feeling never fully comes back. It’s a small price for being cancer-free, but it’s a reality that a 2D photo can't convey.

Practical Steps for Handling the "After"

If you are looking at these pictures because you have an upcoming surgery, stop doom-scrolling. Seriously. Every body heals differently. A photo of a 70-year-old smoker’s excision on their shin will look nothing like a 30-year-old’s excision on their back.

Here is how you actually manage the outcome:

1. Wound care is 90% of the battle. Keep it moist. The "let it scab over" advice is dead. Modern dermatology relies on petrolatum-based ointments (like Vaseline or Aquaphor) to keep the cells hydrated so they can migrate and close the gap faster. A dry wound is a slow-healing wound.

📖 Related: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

2. Sun protection is non-negotiable. New scar tissue has no pigment. If it gets hit by UV rays in the first year, it can "tattoo" the scar a dark, permanent brown. Keep it covered. Use UPF clothing or high-zinc sunscreen once the incision has fully closed.

3. Massage the scar. Once your surgeon gives the green light (usually at the 4-6 week mark), massaging the area helps break up the collagen fibers that cause that "tight" feeling. It makes the scar flatter and more pliable.

4. Manage your expectations of "clear margins." Sometimes the first wide excision isn't enough. If the pathology report comes back and says the cancer was closer to the edge than expected, you might have to go back in for a wider cut. It’s frustrating, but it’s the only way to be sure.

The pictures you see online are the "before" and the "middle." They are rarely the "forever." Melanoma is a beast, but the surgery is a proven cure for localized cases. Trust the process, follow the ointment routine, and remember that a scar is just a physical record of a battle you won.

Next Steps for Your Recovery

If you’ve already had your surgery, start a photo log of your own. Take one picture every three days. When you’re in the thick of it, it feels like nothing is changing, but looking back at a two-week progression will show you just how fast your body is working to repair the damage. If you notice any spreading redness, foul odor, or pus, skip the internet search and call your surgical team immediately—those are the only "pictures" that truly require a professional's immediate eye.