If you’ve spent any time scouring the internet for pictures of turkeys with blackhead disease, you probably expected to see birds with literally black heads. It’s in the name, right? Well, honestly, that’s the first mistake most backyard poultry keepers and even some hobby farmers make. The "blackhead" moniker is a bit of a misnomer. Most of the time, the bird’s head doesn't change color at all, or if it does, it’s a subtle cyanotic blue because the bird is struggling to breathe or its organs are failing. It’s a brutal disease. Formally known as Histomoniasis, it’s caused by a tiny protozoan called Histomonas meleagridis.

This isn't just some minor farmyard sniffle.

For turkeys, this is often a death sentence. While chickens can carry the parasite and look perfectly fine—basically acting as biological Trojan horses—turkeys are incredibly susceptible. You might see a photo of a turkey looking slightly hunched or depressed, and twelve hours later, that bird is gone. It's fast. It’s devastating. And if you’re looking at photos to try and diagnose your own flock, you need to know exactly what you’re looking for because the external signs are often incredibly subtle until it’s far too late to do much about it.

Recognizing the Real Symptoms Beyond the Name

Forget the idea of a soot-colored head. When you look at verified pictures of turkeys with blackhead disease, the most definitive visual cue isn't the head at all; it's the droppings. Experts at the University of Guelph and various avian pathology labs point to "sulfur-yellow" diarrhea as the smoking gun.

It’s a very specific shade of bright yellow.

If you see that on the ground, your heart should probably sink a little. This happens because the protozoa set up shop in the cecal tubes (the blind pouches of the gut) and then migrate to the liver. Once the liver starts failing, the bird’s body can’t process bile correctly, leading to that distinctively colored waste.

You’ll also notice behavioral changes in these photos. Affected turkeys often look "tucked up." They’ll stand with their heads pulled into their shoulders, wings drooping, and feathers ruffled. They look miserable. They stop eating. They stop drinking. In a flock setting, they’ll often huddle together for warmth because their bodies are failing to regulate temperature, but they won't have the energy to compete for space.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

The Earthworm Connection

There is a weird, almost symbiotic relationship between this disease, cecal worms (Heterakis gallinarum), and common earthworms. The Histomonas parasite is fragile. It dies quickly if it's just sitting out in the grass. However, it’s a survivor when it hitches a ride inside the eggs of the cecal worm.

Those eggs get eaten by earthworms.

Then your turkey eats the earthworm.

Boom. Infection.

This is why old-timers will tell you never to run turkeys on ground where chickens have lived in the last three to five years. Chickens are notorious for carrying those cecal worms and shedding the Histomonas parasite without showing a single symptom. You could have a flock of "healthy" Silkies or Rhode Island Reds that are effectively seeding your soil with turkey-killing pathogens every time they poop.

What the Liver Actually Looks Like

If you ever see a necropsy photo—which are often the most accurate pictures of turkeys with blackhead disease available in veterinary journals—the liver is the star of the show, and not in a good way. A healthy turkey liver is smooth and dark red. A liver infected with Histomoniasis looks like it has been hit by a miniature shotgun.

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

It develops these "bullseye" lesions.

They are circular, depressed areas of dead tissue (necrosis) that are yellowish or greenish-grey. They are unmistakable. Dr. Robert Beckstead, a well-known researcher in poultry science, has highlighted how these lesions are the pathognomonic sign of the disease—meaning if you see them, there is no doubt what killed the bird. The cecal tubes will also be filled with a hard, cheesy plug of dead cells and parasite gunk. It’s graphic, but for anyone serious about flock health, these are the images that matter more than a photo of a moping bird in a field.

Why Diagnosis is a Race Against Time

The reason people search so desperately for these images is that there is currently no FDA-approved treatment for blackhead disease in food-producing birds in the United States.

None.

Nitarsone was the go-to for decades, but it was pulled from the market around 2015 due to concerns about arsenic levels. This leaves farmers in a tough spot. If you identify the disease via pictures or symptoms, your options are basically limited to "supportive care" and aggressive biosecurity. Some people swear by herbal remedies like oregano oil or cinnamon, and while there is some research from institutions like NC State University suggesting these might have mild anti-protozoal properties, they aren't a cure. They are a "maybe this helps a little" at best.

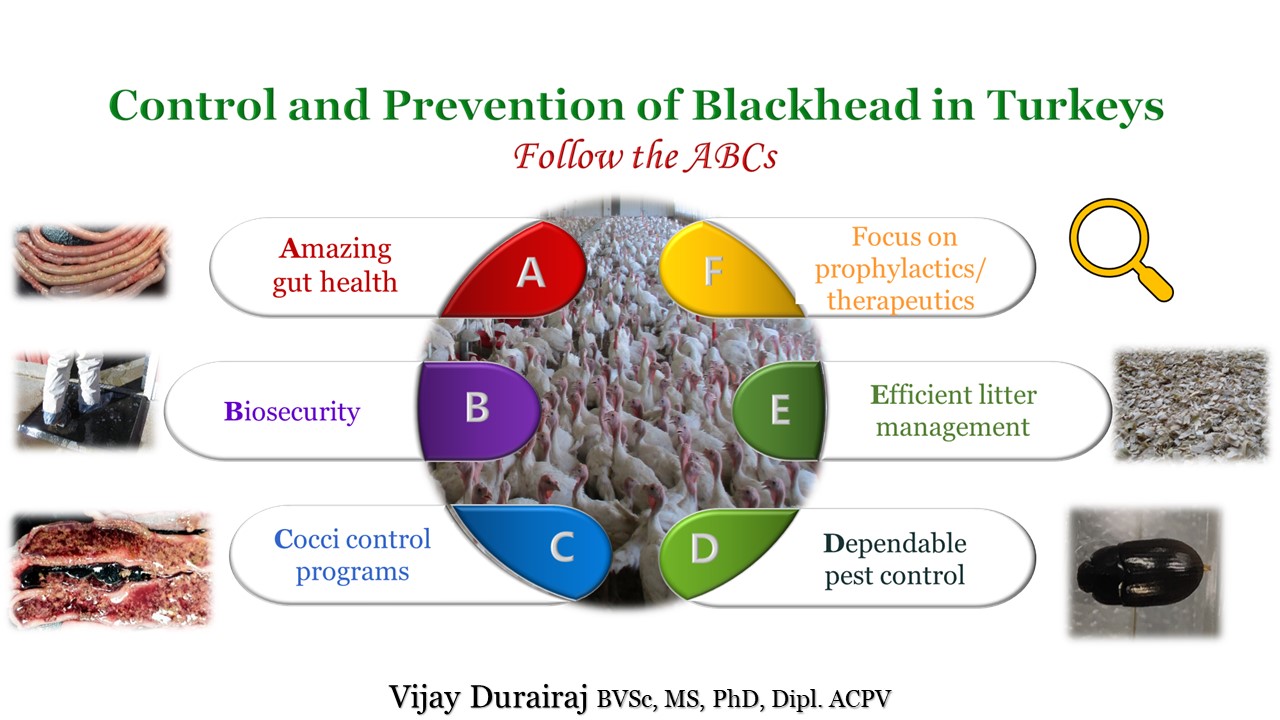

Prevention is the only real strategy.

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

- Keep turkeys and chickens completely separate. No shared fences. No shared equipment.

- Manage your drainage. Parasite eggs love muddy, damp spots.

- Move your pens frequently if you’re on pasture.

- Consider a "wire floor" setup for the first few months of a turkey's life to keep them away from earthworms.

It feels a bit extreme, I know. But when you’ve seen an entire flock of heritage Bronzes or Broad Breasted Whites go from healthy to 80% mortality in a week, you start to take the "extreme" measures pretty seriously.

Actionable Steps for Flock Protection

If you suspect your birds have been exposed or you've seen the dreaded yellow droppings, you need to act immediately. Don't wait for the "black head" to appear, because it probably won't.

First, isolate any bird that looks even slightly "off." If a turkey isn't running to the feeder with the others, it’s sick. Period. Turkeys are stoic until they can't be anymore.

Second, get a definitive diagnosis. If a bird dies, put the carcass in a plastic bag and refrigerate it (don't freeze it) and call your state vet or a local university poultry lab. It might cost $50 or $100 for a necropsy, but knowing for sure if it’s blackhead versus Coccidiosis or E. coli will save you thousands in the long run.

Third, tighten up your footwear. Stop wearing the same boots into the turkey pen that you wore in the chicken coop. The parasite eggs are microscopic and they stick to the tread of your shoes like glue. A simple bleach footbath at the gate of your turkey run is one of the cheapest and most effective ways to stop the spread.

Finally, focus on gut health. While not a cure, a bird with a robust microbiome is generally better equipped to handle a low-level parasitic load than one that is stressed or malnourished. Use probiotics and keep the waterers scrupulously clean. Biofilm in water lines can harbor all sorts of nasties that weaken the immune system, making the Histomonas invasion that much easier.

The reality of blackhead is grim, and the pictures are heartbreaking, but understanding the biology of the parasite—rather than just looking for a color change on a bird’s head—is what actually saves a flock. Stay vigilant about those yellow droppings and keep your chickens and turkeys miles apart (or at least a very solid fence apart) if you want to keep your birds alive.