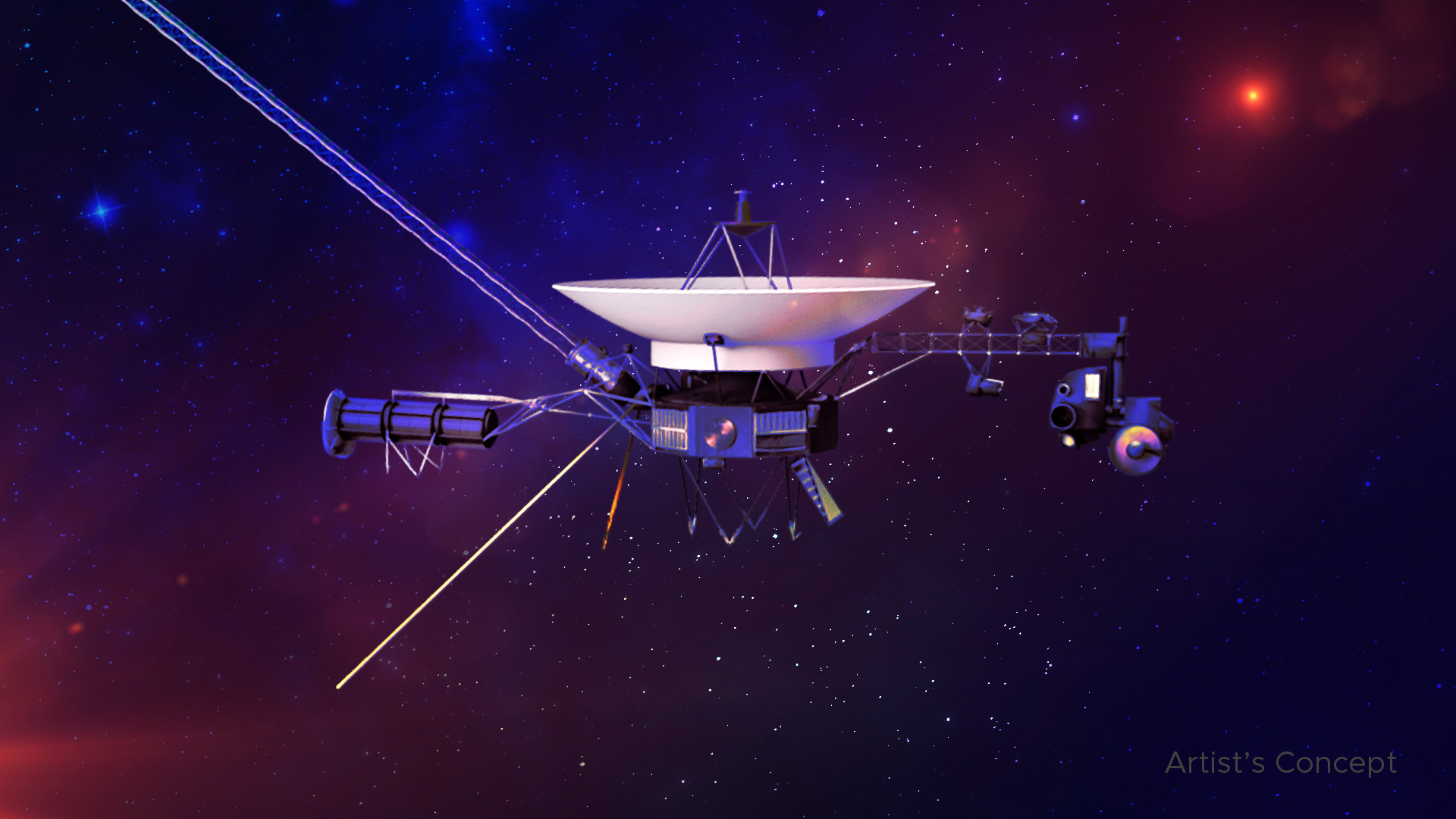

Look at the Pale Blue Dot. No, seriously, pull it up and look at that tiny, grainy pixel suspended in a sunbeam. It’s haunting. When we talk about pictures of the Voyager, most people think of those high-definition, neon-pink shots of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot or the neon-blue rings of Neptune. But the real story is about how two metal boxes launched in 1977 managed to fundamentally change how humans perceive their place in the universe using technology that has less processing power than your car's key fob.

Voyager 1 and 2 weren't just cameras. They were our eyes during a "Grand Tour" that only happens once every 176 years.

Honestly, it’s a miracle they worked at all. The cameras on these probes used vidicon television tubes—basically vacuum tubes—to capture light. They didn't have digital sensors like your iPhone. Instead, they took black and white images through different color filters. Scientists back on Earth had to painstakingly reassemble these layers to show us what the outer solar system actually looked like. If you’ve ever felt frustrated waiting for a 4K video to buffer, imagine waiting sixteen hours for a single 800x800 pixel image to travel across billions of miles of empty space at the speed of light.

The Technical Wizardry Behind Those Grainy Masterpieces

Capturing pictures of the Voyager required a level of mathematical precision that is frankly terrifying. Think about this: Voyager 1 was hurtling through space at roughly 38,000 miles per hour. Taking a photo of a moon like Io or Enceladus while moving that fast is like trying to photograph a speeding bullet from the window of a race car while wearing a blindfold. To avoid motion blur, the engineers had to rotate the entire spacecraft during the exposure to "track" the target.

It worked.

The detail was staggering for the time. Before Voyager, our best views of Jupiter were blurry blobs from ground-based telescopes or the Pioneer flybys. Voyager changed the game. It showed us that Jupiter’s clouds were a chaotic, swirling mess of fluid dynamics. We saw volcanic eruptions on Io—the first time we ever saw active volcanoes on another world. This wasn't just "space photography." It was a geological revolution.

The Problem With Lighting at the Edge of the Sun

Light is a major issue. By the time Voyager 2 reached Neptune, the sunlight was 900 times dimmer than it is on Earth. Taking a photo there is like trying to take a picture in a dimly lit basement with a camera from the 1970s. The exposures had to be incredibly long.

💡 You might also like: How to Convert Kilograms to Milligrams Without Making a Mess of the Math

NASA engineers had to get creative. They used the spacecraft's thrusters to steady the platform to a degree that seems impossible. Even a tiny vibration from the tape recorder (yes, Voyager used a digital tape recorder) could ruin the shot. They actually timed the photos to occur between the mechanical movements of the internal components.

Why the Pale Blue Dot Isn't Just a Photo

You can't discuss pictures of the Voyager without mentioning February 14, 1990. Voyager 1 had finished its primary mission. It was headed out into the interstellar void. Carl Sagan, who was part of the imaging team, begged NASA to turn the camera around one last time. Some engineers were worried. Pointing the camera back toward the Sun might fry the sensitive vidicon tubes.

But they did it.

From nearly 4 billion miles away, Voyager 1 snapped a series of 60 frames. One of them contained Earth. It's barely a point of light. It's less than a pixel wide. It sits in a scattered beam of sunlight caused by the camera's optics. Sagan famously noted that every human who ever lived, every king, every peasant, and every lover, spent their lives on that "mote of dust."

That single image changed environmentalism. It changed philosophy. It proved that space photography isn't just about science; it's about perspective. It’s probably the most important selfie ever taken.

The "Family Portrait" Most People Forget

While the Pale Blue Dot gets all the glory, the "Family Portrait" was actually a mosaic of 60 images. It captured six planets: Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, Earth, and Venus. Mars was lost in the glare of the Sun. Mercury was too close to the Sun to see. This was the first—and only—time a spacecraft has attempted to photograph our solar system from the outside looking in.

📖 Related: Amazon Fire HD 8 Kindle Features and Why Your Tablet Choice Actually Matters

The Weirdness of Voyager 2’s Visit to Uranus and Neptune

Voyager 2 is the only human object to ever visit Uranus and Neptune. Think about that for a second. Every single close-up image we have of those "ice giants" comes from a single flyby in the late 1980s. When you see pictures of the Voyager showing the deep, serene blue of Neptune or the featureless, pale teal of Uranus, you're looking at history that hasn't been updated in forty years.

- Uranus: It looked boring at first. A smooth, featureless cue ball. But when scientists pushed the contrast on the images, they found faint cloud bands.

- Neptune: It was the opposite. It was vibrant. It had the "Great Dark Spot," a storm the size of Earth that vanished by the time the Hubble Space Telescope looked at it years later.

- Triton: Neptune’s moon Triton turned out to be one of the weirdest places in the solar system. Voyager’s photos showed "nitrogen geysers" shooting dark material miles into the thin atmosphere.

We haven't been back. We’re still relying on data from a machine built in the era of disco and bell-bottoms.

The Death of the Cameras

Here is the heartbreaking part. There are no new pictures of the Voyager.

In order to save power and memory for the fields and particles instruments—the tools that measure solar wind and magnetic fields—the cameras were turned off shortly after the Family Portrait in 1990. The software that ran the imaging system has been deleted to make room for other data. Even if we wanted to turn them back on, the spacecraft are now so far away that the Sun is too dim to use as a reference point for the star trackers.

They are flying blind now.

They are still communicating, though. As of 2024 and 2025, Voyager 1 and 2 are in interstellar space. They are sending back data about what it’s like outside the "bubble" of our Sun. But they aren't seeing it. They are just feeling the plasma and the magnetic fields. The era of Voyager photography is over, but the images we have are being re-processed today with modern AI and deconvolution techniques to reveal details we missed in the 80s.

👉 See also: How I Fooled the Internet in 7 Days: The Reality of Viral Deception

How to Access and Use Voyager Imagery Today

If you’re looking for these images, don't just settle for a low-res Google Image search. The raw data is public property.

- NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS): This is where the actual raw files live. They aren't pretty. They are "stretched" and full of static, but they are the real deal.

- JPL’s Photojournal: This is the best place for "cleaned up" versions. Look for the "calibrated" images which have had the camera's internal "noise" removed.

- Amateur Processors: People like Kevin Gill or Björn Jónsson do incredible work taking the old Voyager data and using modern software to create "true color" versions that look like they were taken yesterday.

The legacy of pictures of the Voyager is that they made the solar system a "place" rather than just a collection of points in the sky. We saw the grooves in Saturn's rings. We saw the fractured ice of Europa. We saw ourselves.

To truly appreciate these photos, you have to remember the distance. Voyager 1 is currently over 15 billion miles away. It takes light over 22 hours to travel one way. The fact that we have these images at all is a testament to human curiosity overhauling the limitations of 1970s hardware.

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts:

- Download the Raw Data: Visit the NASA PDS archives to see what an image looks like before the "pretty" colors are added. It gives you a massive appreciation for the scientists who interpreted the data.

- Follow the Voyager Status: Check the JPL "Eyes on the Solar System" real-time tracker. It shows you exactly where the probes are right now and how fast they are moving.

- Explore the Golden Record: Since the cameras are off, the "visuals" Voyager carries now are encoded on a copper phonograph record. Look up the images included on that record—they are the photos we chose to represent humanity to whatever might find the probe in a billion years.

The cameras are cold and dark, but the pixels they sent back remain the definitive maps of the outer frontier. Go look at the Pale Blue Dot again. It’s still there, and so are we.