August 1969. Los Angeles was melting under a heatwave. It was the "Summer of Love," or at least it was supposed to be, until everything curdled on a dead-end drive in Benedict Canyon. When people search for pictures of the tate murders, they aren't usually looking for gore, though the internet provides plenty of that. They’re looking for the end of an era.

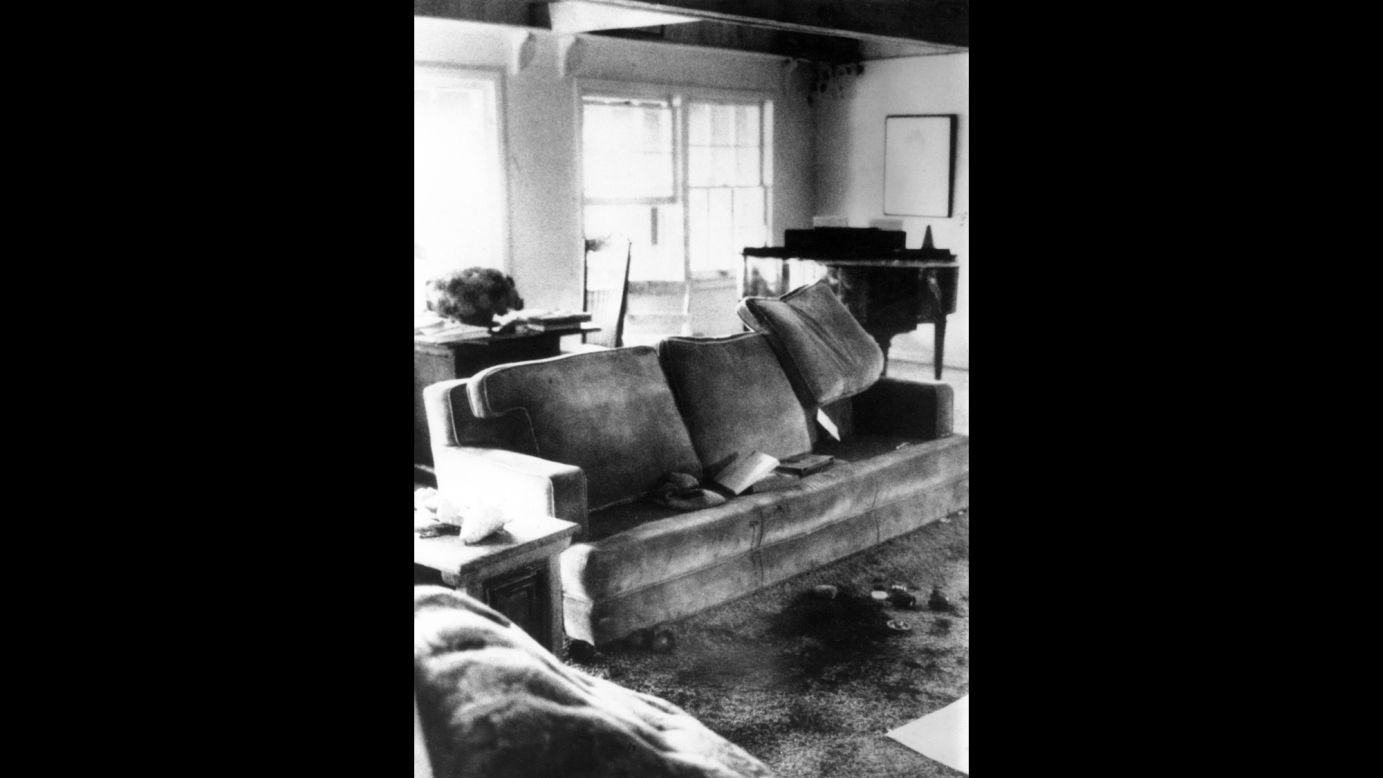

The photos from 10050 Cielo Drive changed everything. Before those grainy, black-and-white crime scene shots hit the wire services, people in Hollywood left their back doors unlocked. They trusted the canyon breeze. After? Security companies became the biggest business in Beverly Hills.

Looking at those images now feels like peering into a fractured mirror of the 1960s. You see the contrast between the glamorous life of Sharon Tate—a rising star, eight and a half months pregnant—and the savage, senseless brutality of the Manson Family. It’s a collision of worlds that shouldn't have touched.

The Crime Scene Photos That Broke the News

The initial pictures of the tate murders weren't the ones we see in true crime documentaries today. They were the exterior shots. The gate. The long, winding driveway. The word "PIG" scrawled in Sharon’s own blood on the front door.

LAPD investigators, including officer Jerry Joe DeRosa who was one of the first on the scene, walked into a literal slaughterhouse. The photos they took for the official record are harrowing. They document the placement of the bodies: Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring in the living room, connected by a long nylon rope; Abigail Folger and Wojciech Frykowski on the front lawn.

These images weren't just evidence. They were a psychological shock to the system. Vincent Bugliosi, the prosecutor who later wrote Helter Skelter, used these photographs to build a narrative of "creepy-crawling" terror. He knew that words couldn't capture the sheer malice of the scene as effectively as a photo of a bloody handprint on a light switch.

Why we can't look away

Human curiosity is a strange, often dark thing. We want to see the photos because we want to understand the "why." But the deeper you go into the Manson case, the less the "why" makes sense.

📖 Related: Dragon Ball All Series: Why We Are Still Obsessed Forty Years Later

Manson wasn't even there for the killings.

He sent Tex Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Linda Kasabian. The pictures show the aftermath of a group of middle-class kids who had been completely hollowed out and refilled with a madman’s ramblings about an apocalyptic race war.

When you look at the photos of the suspects being led into court—smiling, singing, with X's carved into their foreheads—the contrast with the grim crime scene photos is nauseating. It’s that dissonance that keeps the case alive in the public imagination.

The Media's Role in Spreading the Images

In 1969, there was no internet. No social media. Information moved at the speed of the morning edition. Yet, the pictures of the tate murders spread like wildfire.

Life magazine and Newsweek ran features that hovered right on the edge of exploitation. They showed the body bags being wheeled out. They showed Roman Polanski, Sharon’s husband, returning to the house, looking absolutely destroyed.

There’s one famous photo of Polanski sitting in the doorway of the house, staring at the dried blood on the porch. It’s devastating. It humanizes a tragedy that the "Manson Mythos" often tries to turn into a cartoonish horror story.

👉 See also: Down On Me: Why This Janis Joplin Classic Still Hits So Hard

Misconceptions about the crime scene

People often get the details wrong.

- The Rope: Many think the rope around Sharon and Jay’s necks was used for the actual killing. It wasn't. It was used to keep them controlled, draped over a ceiling beam.

- The Motive: People think Manson picked Sharon Tate. He didn't. He picked the house. He wanted to scare Terry Melcher, a record producer who had lived there previously and refused to give Manson a recording contract.

- The Number of Victims: While the Tate murders are the most famous, the pictures from the next night at the LaBianca residence are just as chilling, showing the words "Healter Skelter" [sic] smeared on the fridge.

The Ethics of the True Crime Gaze

Is it "wrong" to look?

In 2026, the true crime industry is a multi-billion dollar machine. We have podcasts, Netflix specials, and deep-dive YouTube essays. But there’s a line between historical documentation and "murderabilia."

The family of Sharon Tate, specifically her late sister Debra Tate, spent decades fighting against the glorification of the Manson Family. Every time a new "unseen" photo of the crime scene surfaces on a fringe forum, it’s a fresh wound for the survivors.

However, these pictures also serve as a grim reminder of the dangers of cult personality. They are a record of what happens when a society’s fringe elements are allowed to fester into radicalization. They are historical artifacts, as much as we might wish they weren't.

The impact on pop culture

From Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time in Hollywood to the countless depictions of Manson in American Horror Story or Mindhunter, the visual language of the Tate murders is everywhere.

✨ Don't miss: Doomsday Castle TV Show: Why Brent Sr. and His Kids Actually Built That Fortress

Tarantino notably chose not to show the actual murders, opting for a revisionist fantasy where the victims fight back. This was widely seen as a respectful nod to the victims, acknowledging that the real pictures of the tate murders are too horrific to be used for mere entertainment.

How to Approach This History Respectfully

If you’re researching this topic, it’s basically essential to center the victims.

Sharon Tate wasn't just a "Manson victim." She was a daughter, a sister, and a talented actress who was about to become a mother. Jay Sebring was a pioneer in the men's hair styling industry. Abigail Folger was a social worker and heiress to a coffee fortune. Wojciech Frykowski was an aspiring screenwriter. Steven Parent was just an 18-year-old kid in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Focusing on their lives rather than just the grainy, black-and-white images of their deaths is the only way to truly honor the history.

Actionable insights for true crime researchers:

- Verify your sources. Many photos circulating online as "Tate murder pictures" are actually from movie sets or unrelated crimes. Use reputable archives like the Associated Press or the California State Archives.

- Read the primary documents. Don't just look at the photos. Read the trial transcripts. Read the autopsy reports if you must, but do so with the understanding that these were real people.

- Support victim advocacy. If you consume true crime content, consider donating to organizations like the National Center for Victims of Crime. It balances the "entertainment" aspect with actual support for those affected by violence.

- Acknowledge the bias. Most early reporting on the Tate murders was laced with 1960s-era prejudices about "hippies" and "drug culture." Look past the sensationalist headlines to find the facts of the case.

The fascination with the pictures of the tate murders isn't going away. They represent a tipping point in American history—the moment the lights went out on the psychedelic dream. By looking at them through a lens of historical context rather than morbid curiosity, we can understand the gravity of what was lost that night in August.

Next Steps for Deeper Understanding:

To get a factual, non-sensationalized view of the legal proceedings, look into the digital archives of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office. For a cultural perspective on how the media handled the imagery at the time, the UCLA Film & Television Archive holds significant broadcast news footage from the 1969-1971 period that provides context often missing from modern internet summaries.