History is usually a blur of dates and dusty names, but the Oregon Trail is different. It’s visual. When you think about it, you probably see a line of canvas-topped wagons snaking through a desert or a family standing awkwardly beside a massive rock. Those pictures of the Oregon Trail—the real ones, etched into glass plates or captured on early film—tell a story that text books usually sanitize. They show the grit. They show the actual, bone-deep exhaustion of people who walked 2,000 miles because they thought life might be better on the other side of the continent.

Honestly, it's a miracle we have any photos at all.

Photography in the mid-19th century wasn't a "point and shoot" situation. It was a massive logistical nightmare involving toxic chemicals, heavy glass plates, and a darkroom that was basically a tent prone to blowing away in a Kansas windstorm. Most of the iconic images we associate with the trail actually come from the tail end of the era, or from the surveyors and professional photographers who retraced the steps of the pioneers just as the wagon wheels were being replaced by iron rails.

The Reality Behind Those Grainy Landscapes

If you look at early pictures of the Oregon Trail, you'll notice something immediately: nobody is smiling. That’s partly because of long exposure times, sure. You had to hold still or you’d turn into a ghost on the plate. But it’s also because the trail was a brutal, grueling slog. By the time a photographer like William Henry Jackson was capturing the landmarks of the West in the 1860s and 70s, the trail was already a graveyard of dreams and literal livestock.

The images of Chimney Rock or Independence Rock aren't just pretty travel photos. They were psychological milestones. Imagine walking for weeks through a flat, featureless horizon and finally seeing that spire of rock poking out of the Nebraska plains. For the emigrants, that was the "I'm actually doing this" moment. Photographers focused on these landmarks because they were the only things that stayed still in a landscape defined by constant, agonizing movement.

The dust was everywhere. You can almost see it in the hazy backgrounds of the old daguerreotypes. It got into the food, the water, and the very pores of the people living out of those wagons. When we look at pictures of the Oregon Trail today, we’re seeing a version of the West that was already being "tamed" by the lens, but the harshness still leaks through the edges.

👉 See also: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

The Problem with the "Wagon Train" Myth

We’ve all seen the paintings and the movie stills of hundreds of wagons lined up in a perfect circle. Real photos tell a messier story. Most of the time, the "trail" wasn't a single path; it was a wide, trampled corridor. People spread out to avoid the dust of the wagon in front of them.

Historical photographs, like those preserved by the National Archives or the Oregon Historical Society, show a landscape that was surprisingly crowded. This wasn't a lonely trek through an empty wilderness. In peak years, like 1852, it was a moving city. There were traffic jams at river crossings. There were massive piles of abandoned furniture—pianos, heirlooms, heavy stoves—left on the side of the road because the oxen were dying of exhaustion.

Portraits of a People Who Had No Idea What They Were Doing

Some of the most haunting pictures of the Oregon Trail aren't of the scenery at all. They’re the portraits. Look at the faces of the women. While the men were often focused on the logistics of the livestock and the route, the women were trying to maintain some semblance of a "home" while moving fifteen miles a day.

They were cooking over buffalo chips. They were washing clothes in muddy streams.

- Solomon Butcher's photography, though slightly later and often focused on homesteaders in Nebraska, captures the spirit of the era perfectly.

- You see families standing in front of sod houses or wagons, clutching their most prized possessions—sometimes a cow, sometimes a fiddle.

- These photos show the transition from "traveler" to "settler."

There's a specific kind of hardness in the eyes of the people in these images. They had seen things we can't quite wrap our heads around. Cholera was the real villain of the trail, not "outlaws" or even the terrain itself. It could rip through a camp in hours. A family might start the week with five children and end it with three. There are no photos of those burials—nobody wanted to remember that—but the emptiness in the family portraits that follow tells the whole story.

✨ Don't miss: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Landmarks Look Different Today

If you go to Mitchell Pass or Scotts Bluff today and compare it to 19th-century pictures of the Oregon Trail, you’ll notice the erosion. These monuments are literally disappearing. Wind and rain are carving them down, but the wagons did their part too. In places like Guernsey, Wyoming, you can see "wagon ruts" carved five feet deep into the solid sandstone.

Those ruts are perhaps the most visceral "pictures" we have. They aren't images on paper; they are physical scars on the earth. Seeing a photograph of a person standing in a rut that reaches their waist gives you a sense of scale that no map ever could. It took half a million people and decades of iron-rimmed wheels to grind that stone into powder.

The Technology That Captured the West

We have to talk about the cameras. The men who took these photos were basically explorers themselves.

William Henry Jackson is probably the most famous. He worked for the Hayden Geological Survey. He lugged his "beast" of a camera—a massive thing that took 20x24 inch glass plates—up mountains. He had to find water to wash his plates in the middle of a desert. If the water was too alkaline, the photo was ruined. If a mule tripped and broke the glass, weeks of work vanished.

Because of these technical limitations, the pictures of the Oregon Trail we have tend to be very "still." We don't have many action shots of a wagon fording a river or a stampede. Everything is posed. Everything is deliberate. This has shaped our view of the trail as a slow, majestic procession, when in reality, it was likely loud, smelly, and incredibly chaotic.

🔗 Read more: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions Fed by Early Media

By the time photography became widespread, the Oregon Trail was already becoming a legend. Stereographs—those double-image cards you’d look at through a viewer to see in 3D—were the "virtual reality" of the 1800s. People in the East would sit in their parlors and look at pictures of the "Great American Desert."

This led to a bit of a romanticized view. Photographers chose the most dramatic vistas. They captured the "noble" struggle. They rarely captured the dysentery or the monotonous weeks of seeing nothing but sagebrush. So, while these photos are technically "accurate," they are also curated. They are the Instagram feeds of the 1870s.

How to Find "Real" Trail Photos Today

If you're looking for the real deal, you have to dig past the stock photos of actors in bonnets.

The Oregon Trail Ruts State Historic Site has some of the best documentation of the physical trail. The National Frontier Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri, houses a massive collection of diaries and associated imagery. But for the actual photographs, the Yale Collection of Western Americana is the gold standard.

When you look at these archives, pay attention to the backgrounds. Look at the state of the wagons. Notice the lack of trees—most had been cut down for firewood by the thousands of travelers who passed through before. These small details are where the real history lives.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Trail Visually

If you're a history buff or just someone who wants to understand the grit of the American West, don't just look at the photos online. Do this instead:

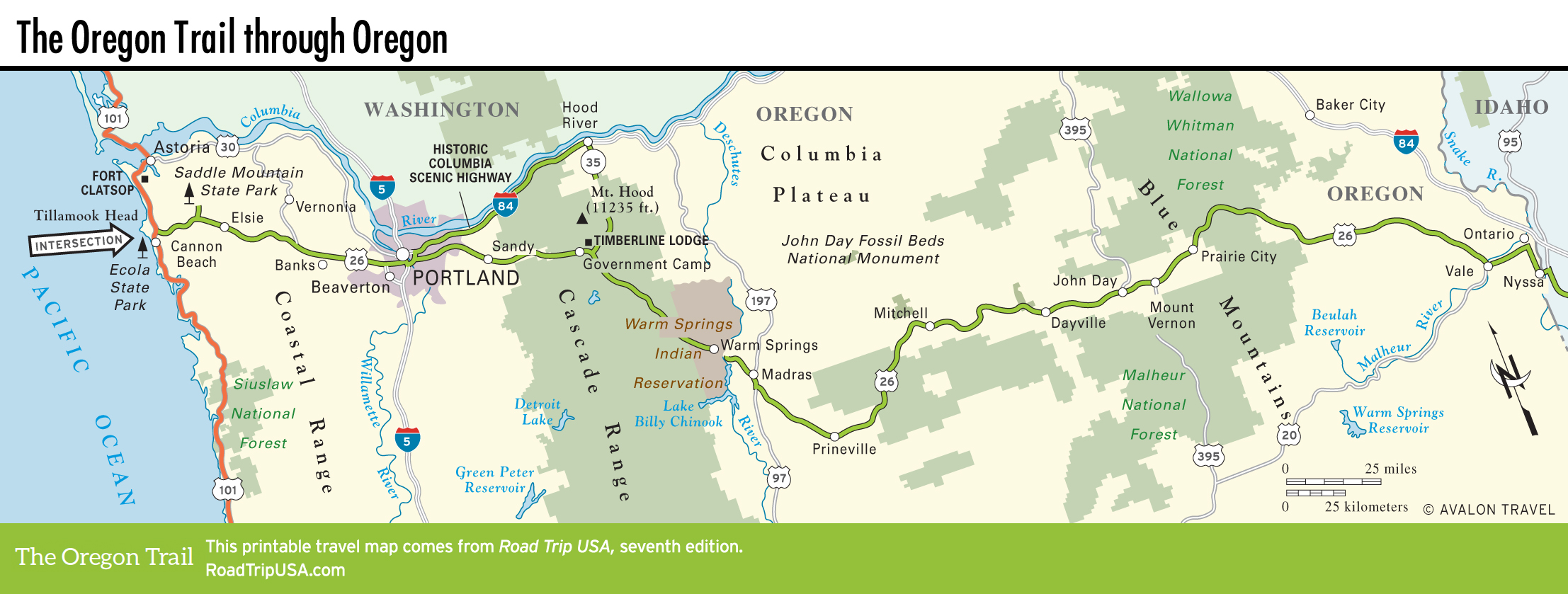

- Visit the "Living" Photos: Go to places like the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center in Baker City, Oregon. They have massive windows that look out over the actual ruts. Seeing the ruts while looking at the archival photos provides a context that a screen just can't replicate.

- Compare the Surveys: Look at the sketches from the 1840s (pre-photography) and compare them to the photos from the 1860s. You can see how the landscape changed as more people moved through.

- Check the Diaries: Read the diary of someone like Narcissa Whitman or Amelia Stewart Knight while looking at photos of the landmarks they mention. It turns a silent image into a visceral narrative.

- Support Digital Archiving: Many local historical societies along the trail (in towns you've never heard of in Wyoming or Idaho) are currently digitizing private family collections. These "unseen" photos are often more honest than the professional survey pictures.

The Oregon Trail wasn't just a road. It was a massive, collective gamble. The pictures of the Oregon Trail that survive today are the only evidence we have of the moment the world started to get smaller, and the "Great American West" started to become a memory instead of a wilderness. They remind us that history isn't just something that happened; it was something people survived.