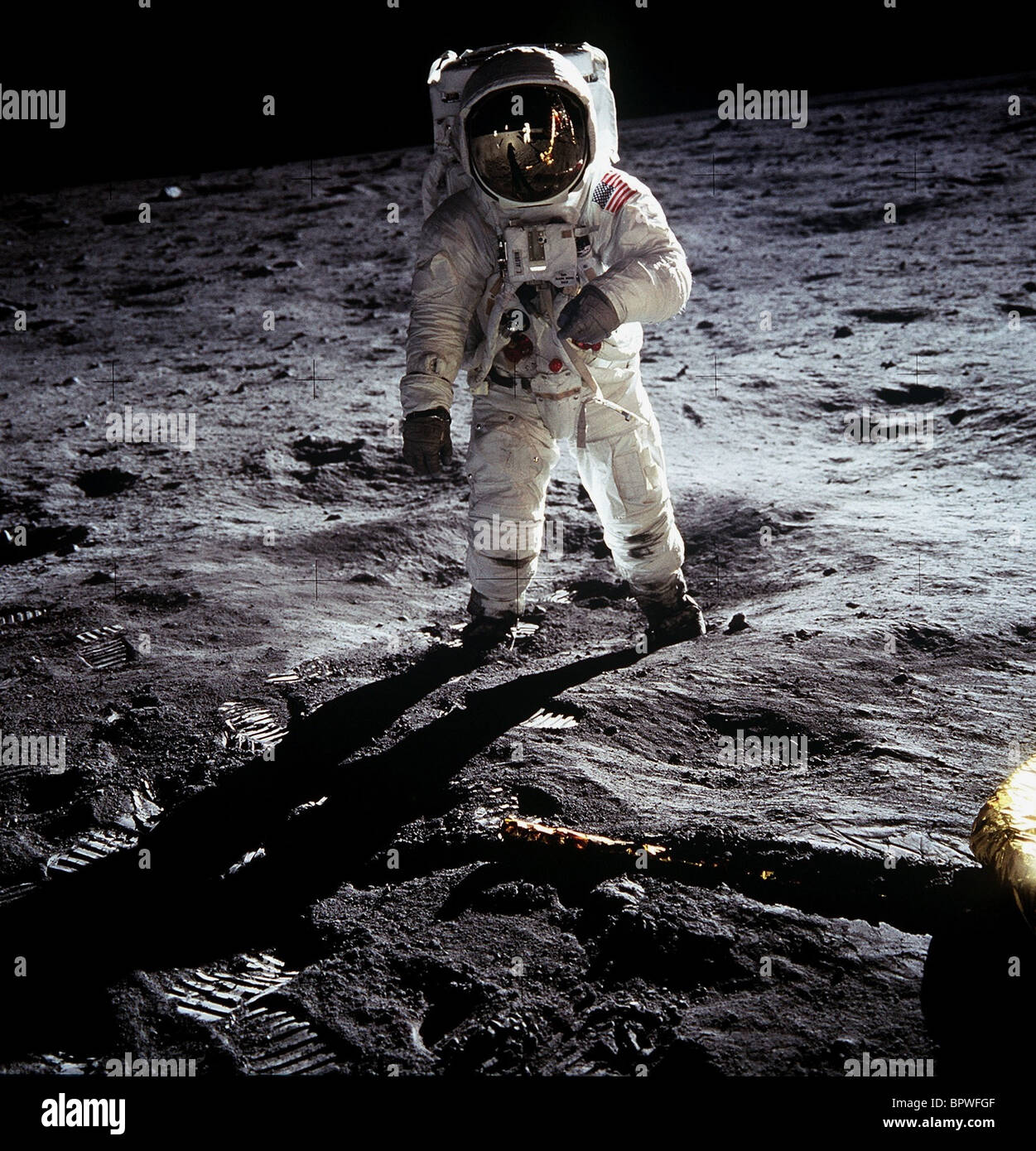

Everyone thinks they know the pictures of the moon landing 1969 like the back of their hand. You’ve seen the visor. You’ve seen the footprint. It’s basically the wallpaper of the 20th century. But when you actually sit down and stare at these frames, things get weird.

Neil Armstrong didn't take the famous photo of the guy on the moon. Buzz Aldrin did. Well, wait. Actually, most of the iconic shots are of Buzz, because Neil was the one holding the camera for the vast majority of the EVA (Extravehicular Activity). Neil was the "tourist" with the expensive Hasselblad strapped to his chest, while Buzz was the one doing the "modeling."

It’s kind of a funny dynamic when you think about it. Two guys on the most desolate rock in existence, and one of them is basically the designated Instagram boyfriend.

The Gear Behind the Pictures of the Moon Landing 1969

NASA didn't just hand these guys a point-and-shoot. They used heavily modified Hasselblad 500EL cameras. They had to be modified because, honestly, space is a nightmare for photography. You’ve got extreme temperature swings—think boiling hot in the sun and freezing in the shade—and a complete lack of atmosphere.

Silver finish. That was the key. They painted the cameras silver to reflect the brutal solar radiation. They also stripped out the viewfinders. Think about that for a second. Neil Armstrong was taking these legendary shots without being able to look through a lens to see what he was framing. He was aiming from the chest. It’s essentially the ultimate "spray and pray" technique, yet the framing in those pictures of the moon landing 1969 is almost hauntingly perfect.

Then there’s the film. Kodak developed special thin-base Estar film so they could cram more exposures into a single magazine. If they had used standard film, they would have run out of "storage" before the flag even went into the ground.

Why Do the Shadows Look So Weird?

If you spend five minutes in a conspiracy forum, you’ll hear people screaming about the shadows. "They aren't parallel!" they say. "There must be multiple studio lights!"

Here’s the thing about lunar topography: it’s lumpy.

🔗 Read more: How I Fooled the Internet in 7 Days: The Reality of Viral Deception

When you have a single light source—the Sun—hitting a surface that isn't flat, shadows are going to warp. It’s basic perspective. If you stand on a hill at sunset on Earth, your shadow doesn't look like a perfect geometric projection either. In the pictures of the moon landing 1969, the lunar surface is a chaotic mess of craters, rises, and dips.

Also, the lunar soil (regolith) is weirdly reflective. It has this property called "backscatter" or Heiligenschein. Basically, the dust reflects light back toward the source, which acts like a giant, natural fill light. That’s why you can see details on the "dark" side of the Lunar Module or on the front of Buzz’s suit even when he’s standing in a shadow. It’s not a Hollywood reflector; it’s just physics behaving differently than it does in your backyard.

The "Missing" Stars and Other Optical Illusions

"Where are the stars?"

This is the big one. People look at the pitch-black sky in those photos and assume it’s a black curtain in a studio. But ask any photographer about dynamic range.

The moon is bright. Like, really bright.

The astronauts were standing in direct, unfiltered sunlight on a surface that’s essentially the color of asphalt but reflects light like concrete. To get a clear shot of a bright white spacesuit in that environment, you have to use a short exposure time. If you kept the shutter open long enough to capture the faint light of distant stars, the astronauts and the moon itself would be a blown-out, white glowing blob. You can’t have both. It’s a technical limitation of film, not a conspiracy.

The Crosshairs and the "Layering" Myth

Check out the little black crosses in the pictures of the moon landing 1969. Those are called Réseau plate markings. They were etched into a glass plate inside the camera to help scientists measure distances and scales in the photos later on.

💡 You might also like: How to actually make Genius Bar appointment sessions happen without the headache

A common "gotcha" people try to use is pointing out photos where the crosshairs seem to be behind an object, like a piece of equipment. They claim this proves the photos were composited. In reality, it’s just a phenomenon called "bleeding." When a white object is incredibly bright and overexposed—like a sunlit lunar lander—the white pixels (or silver halides on film) bleed over the thin black line of the crosshair. It’s an optical overflow.

That One Famous Shot: The Visor Reflection

If there is one image that defines the era, it’s the shot of Buzz Aldrin standing slightly turned, with the entire lunar landscape—including Neil Armstrong and the Eagle—reflected in his gold-plated visor.

It’s a masterpiece.

What’s wild is that it was almost an accident. Neil saw the reflection and snapped it. If you look closely at the high-res scans from the Project Apollo Archive, you can see the shadow of the camera and Neil's silhouette. It is perhaps the most famous "selfie" ever taken, even if it’s a secondary reflection.

The Reality of Developing the Film

When the Apollo 11 crew splashed down, the film was arguably the most valuable cargo on the ship (aside from the rocks and, you know, the humans). It went through a grueling decontamination process. NASA was legitimately terrified of "space germs" back then.

The film magazines were whisked away to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston. Can you imagine being the technician tasked with developing the first-ever pictures of the moon landing 1969? One chemical spill and you've accidentally erased the greatest visual record in human history. No pressure.

Dick Underwood, NASA’s photography chief at the time, was the guy who oversaw this. He insisted on a "precision processing" method that was way more intense than your local pharmacy's one-hour photo lab. They used a machine called the Hi-Speed Pako Processor, and the chemicals were monitored to the fraction of a degree.

📖 Related: IG Story No Account: How to View Instagram Stories Privately Without Logging In

How to Spot a Genuine 1969 Print

If you ever find yourself at an auction or a high-end estate sale, you might see "vintage NASA red-letter prints." These are the holy grail for collectors.

- Look for the red serial number in the top corner (usually starting with AS11).

- Check the paper stock; most originals were printed on "A Kodak Paper."

- The fiber-based paper has a specific weight and feel that modern inkjet prints can't replicate.

- Genuine prints from the late 60s often have a slight "curl" to them because of the way the emulsion dries over decades.

Why We Keep Looking

We live in an age of AI-generated images and deepfakes. You can prompt a computer to "make a photo of an astronaut on Mars eating a taco" and it’ll do it in three seconds.

But the pictures of the moon landing 1969 hit different because they are gritty. They have grain. They have "mistakes"—like the lens flares or the slightly tilted horizons. They represent a moment when humanity actually left the porch and stepped into the street.

There’s a rawness to the film that digital can’t touch. It’s a physical record of light hitting a strip of plastic 238,000 miles away.

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you want to move beyond the low-res versions you see on social media, there are actual ways to engage with this history properly.

- Visit the Project Apollo Archive on Flickr. This is a massive, high-resolution repository of the raw Hasselblad scans. You can see the blurry shots, the "accidental" photos of the ground, and the stunning panoramas in their original, uncropped glory.

- Check out the "Apollo 11 Sourcebook." It’s a technical breakdown of every piece of equipment used, including the optical specs of the lenses.

- Look for "First Man" by James R. Hansen. It’s the definitive biography of Armstrong and goes into great detail about the training they underwent just to operate the cameras in those bulky pressurized gloves.

- Verify the metadata. If you see a "newly discovered" photo on X or TikTok, cross-reference it with the NASA image IDs (like AS11-40-5903). If it doesn't have an ID, it’s probably a modern render.

The moon landing wasn't just a feat of engineering; it was a feat of documentation. We didn't just go; we made sure we could prove we were there, and those photos remain the most enduring evidence of what we’re capable of when we stop arguing and start building.