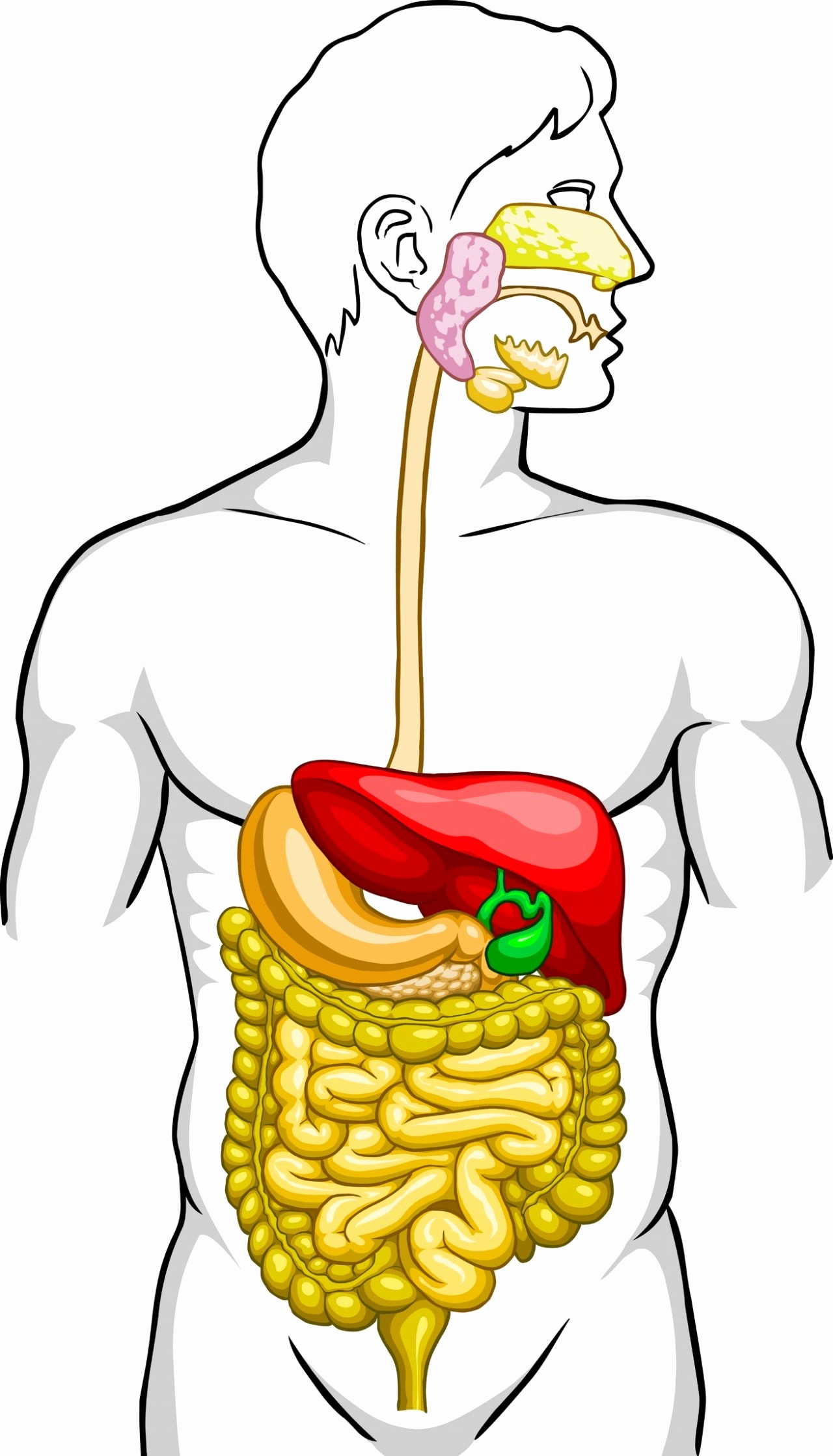

You’ve probably seen them a thousand times in biology textbooks or doctor’s offices—those bright, neon-colored pictures of the digestive system of human bodies that make everything look like a perfectly organized plumbing job. Pink stomach. Bright green gallbladder. A neatly coiled pile of intestines that looks suspiciously like a garden hose.

It’s all a bit of a lie, honestly.

Inside a living, breathing person, your insides aren't neon. They’re glistening, dark, and constantly in motion. If you actually saw a high-definition medical photograph of a working gut, you might not even recognize it compared to the sanitized diagrams we grew up with. This matters because how we visualize our internal organs changes how we treat them. Most people think of their digestion as a static pipe. It’s actually a sophisticated, neurological, and muscular "second brain" that covers about 30 feet of space inside you.

The Problem with Traditional Pictures of the Digestive System of Human Anatomy

Most medical illustrations simplify things so we don't get overwhelmed. That’s fair. But it leads to some pretty big misconceptions. For instance, many people look at a 2D diagram and assume the stomach is located right behind the belly button. Nope. Your stomach is actually much higher up, tucked under your ribs on the left side. If you're feeling pain right at your navel, you're likely looking at your small intestine, not your "stomach" in the anatomical sense.

Then there’s the scale.

The small intestine is roughly 20 feet long. Think about that. That’s the height of a two-story building crammed into your midsection. Standard pictures of the digestive system of human anatomy often fail to show the mesentery, which is this thin, fan-like sheet of tissue that anchors the intestines to the back of the abdominal wall. Without it, your guts would just tangle into a knot every time you did a cartwheel. In 2016, researchers at the University of Limerick, led by J. Calvin Coffey, actually reclassified the mesentery as a continuous organ rather than just a bunch of fragmented membranes. You won't find that in older diagrams.

👉 See also: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Beyond the "Pink Tube": What’s Really Happening in There?

When you look at a diagram, you see the esophagus, the stomach, and the intestines. But the real magic happens in the parts that are hard to draw.

The Mouth and the Secret Enzymes

Digestion starts before you even swallow. Saliva contains amylase, an enzyme that begins breaking down carbohydrates immediately. If you chew a piece of plain bread long enough, it actually starts to taste sweet. That’s chemistry in real-time. Most illustrations show the mouth as just a "hole," but it’s the primary mechanical processor of the entire system.

The Esophageal Slide

The esophagus isn't just a gravity-fed slide. It uses peristalsis, which are rhythmic, wave-like muscle contractions. This is why you can technically eat or drink while hanging upside down—though I wouldn't recommend it for Sunday brunch. It’s a muscular feat that happens in seconds, yet it’s often depicted as a simple, passive tube in many pictures of the digestive system of human models.

The Stomach’s Acid Bath

Your stomach is a rugged, muscular bag. It’s lined with rugae, which are folds that allow it to expand like an accordion when you overindulge at Thanksgiving. The hydrochloric acid inside is strong enough to dissolve metal, yet the stomach doesn't digest itself because it secretes a thick layer of mucus. When that mucus layer fails, you get ulcers. It’s a violent, acidic environment that looks more like a churning cement mixer than the "pouch" you see in drawings.

The Microbiome: The Invisible Layer

Here is where almost every picture fails. You cannot see the most important part of the human digestive system with the naked eye. We are talking about trillions of bacteria, fungi, and viruses—collectively known as the gut microbiome.

✨ Don't miss: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

If you were to look at a "true" picture of the digestive system, it would have to be covered in a microbial "fuzz." These microbes outnumber your human cells. They influence your mood by producing serotonin, they train your immune system, and they help break down fibers that your own enzymes can't touch. Experts like Dr. Rob Knight, co-founder of the American Gut Project, have shown that the diversity of these "bugs" is a better predictor of health than almost any other metric. Yet, when we search for pictures of the digestive system of human anatomy, we usually get a sterile, bacteria-free version. It's like looking at a map of a city but leaving out all the people living in it.

Why the Liver and Pancreas are the Unsung Heroes

People often focus on the "tube" (the gut), but the accessory organs do the heavy lifting. The liver is a chemical processing plant. It performs over 500 functions, including detoxifying your blood and producing bile to break down fats. It’s huge—the largest internal organ—and it sits mainly on your right side.

Then there’s the pancreas. It’s tucked away behind the stomach. It’s small, but if it stops working, everything falls apart. It shoots out bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid as it enters the small intestine. Without that, the acid would literally burn a hole through your gut. It also regulates your blood sugar. In most pictures of the digestive system of human bodies, the pancreas is a little yellowish blob that looks unimportant. In reality, it’s the master regulator of your metabolic life.

Real-World Implications of Poor Visualization

Why does this matter? Because when we have a "cartoon" understanding of our bodies, we make poor health choices. We buy "detox teas" thinking we’re flushing out a literal pipe. But that's not how it works. Your liver and kidneys are the detox system. You can't "scrub" your intestines with a juice cleanse; you can only support the biological processes that are already happening.

Understanding the complexity—the folds, the surface area, the bacterial colonies—helps you realize that gut health is about balance, not "cleaning." The small intestine alone has a surface area roughly the size of a tennis court thanks to microscopic finger-like projections called villi. When you realize your gut is that vast and delicate, you start to think twice about processed foods that can inflame those tiny structures.

🔗 Read more: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

Seeing the System Differently

If you want to truly understand your anatomy, look for 3D medical renders or actual endoscopic photography. These provide a much more accurate sense of the "wet" environment of the body. You’ll see that the large intestine (the colon) isn't just a lumpy tube; it’s a segmented, highly active organ that reabsorbs water and houses the bulk of your microbiome.

It’s also worth noting that the "standard" male-centric model often used in pictures of the digestive system of human anatomy doesn't always account for how the female reproductive system displaces the gut. During pregnancy, the intestines are literally shoved upward and backward, which is why heartburn and constipation are so common. Everything is interconnected. Nothing exists in a vacuum.

Moving Forward with Your Gut Health

Stop thinking of your digestion as a simple conveyor belt. Instead, view it as an ecosystem. To actually use this knowledge for your health, focus on the following shifts:

- Feed the "Invisible" System: Since pictures don't show the microbiome, we forget it's there. Eat diverse fibers (leeks, asparagus, onions, garlic) to feed the bacteria that manage your immune system.

- Respect the Transit Time: It takes about 24 to 72 hours for food to move through the whole system. If you're feeling bloated today, it might be from something you ate two days ago.

- Hydrate for the "Sliding": Peristalsis and mucus production require significant water. Without it, the "plumbing" metaphor becomes reality—things get stuck.

- Check the Source: When looking at medical diagrams, ensure they include the "accessory" organs like the gallbladder and pancreas, as these are often where the most critical health issues (like stones or enzyme deficiencies) occur.

- Listen to the "Second Brain": The enteric nervous system in your gut contains more neurons than your spinal cord. If your "gut feeling" says something is wrong—even if a standard diagram says you're fine—pay attention to those signals of bloating, lethargy, or discomfort.

The human body is remarkably resilient, but it’s also incredibly crowded. Understanding where things actually sit—and how they actually look—is the first step in taking care of the complicated machinery that keeps you alive.