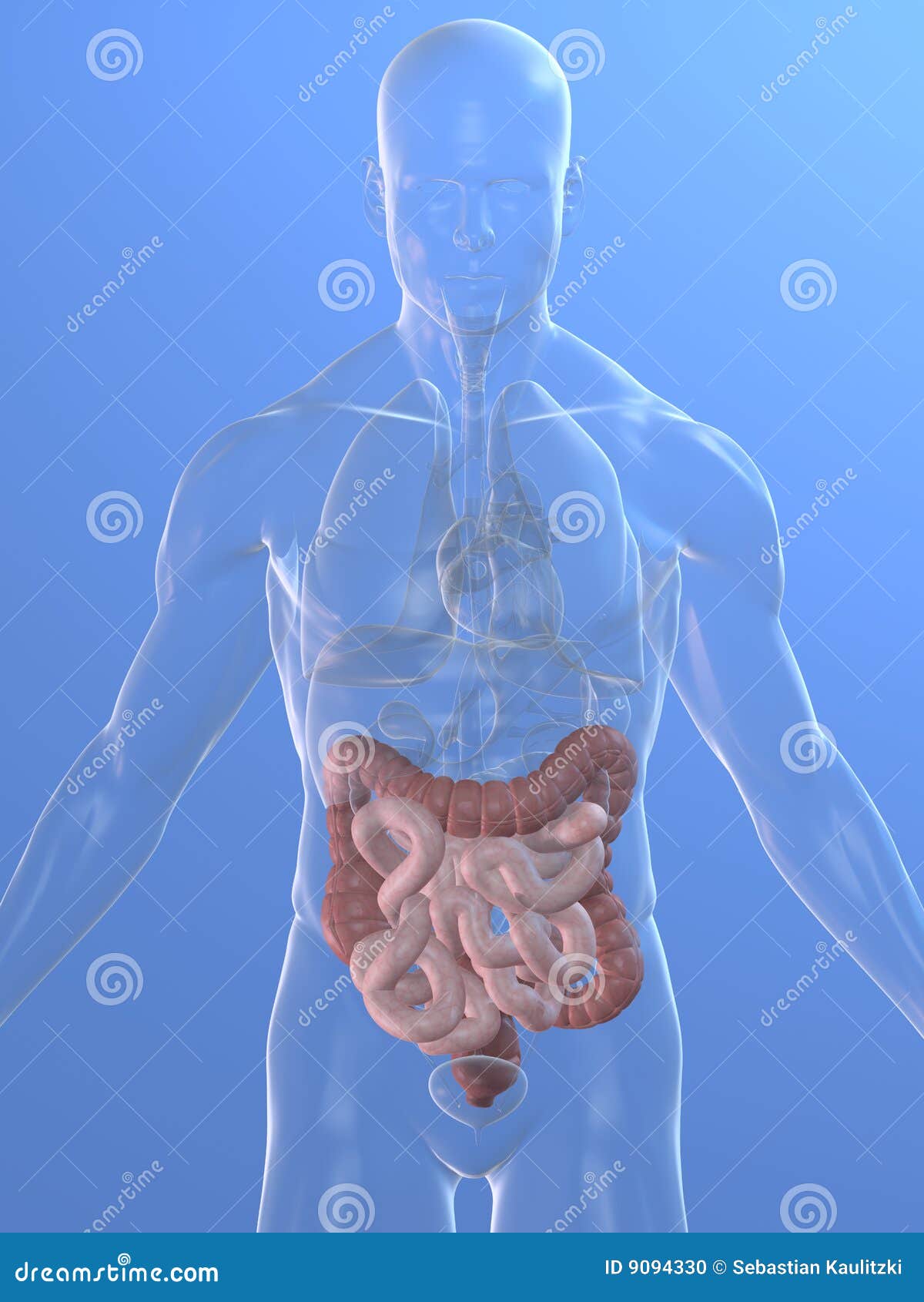

So, you’re curious about what’s actually going on inside your gut. Most people are, honestly. We spend a lot of time thinking about what we put into our bodies, but once that food clears the throat, it’s basically a black box for most of us. Then you see pictures of the colon and intestines online—maybe a glossy medical illustration or a grainy colonoscopy shot—and it looks... weird. It’s not just a smooth tube like a garden hose. It’s complicated. It’s wet. It’s colorful in ways you didn't anticipate.

When you look at these images, you’re seeing one of the most sophisticated "sorting facilities" on the planet. Your small intestine alone is roughly 20 feet of coiled power, followed by about five feet of the large intestine, or colon. They aren't just sitting there like a pile of rope. They are alive, constantly pulsing with something called peristalsis.

Most people expect to see bright red or maybe a generic "flesh" tone. In reality, a healthy colon—when viewed through a scope—is often a pale, glistening pink. It’s almost pearly. If it’s bright red or angry-looking, that’s usually a sign of inflammation, which is why doctors get so picky about the quality of the photos they take during procedures.

What You’re Actually Seeing in Pictures of the Colon and Intestines

If you’ve ever scrolled through medical journals or even just clicked on a Wikipedia entry for the digestive system, you’ve probably noticed two very different types of visuals. You have the "clean" anatomical drawings and the "real" clinical photos.

The anatomical drawings are great for learning where things are. They show the ascending colon on the right, the transverse colon across the top, and the descending colon on the left. It looks like a nice, neat frame around the small intestine. But real life? It's messy. Everything is packed in tight. There’s a yellow, fatty tissue called the omentum that drapes over these organs like a protective apron. It's often ignored in basic sketches, but it's prominent in any real surgical photo.

The Small Intestine: The Velvet Tunnel

Under a microscope, the small intestine looks like a shag carpet. This is because of the villi. These are tiny, finger-like projections that increase the surface area for nutrient absorption. If you flattened out a human small intestine, it would cover the surface of a tennis court. Think about that. 20 feet of tube with the surface area of a sports arena. When you see high-resolution pictures of the colon and intestines, specifically the mucosal lining of the small bowel, you are seeing millions of these tiny structures working to pull glucose, amino acids, and fats into your bloodstream.

📖 Related: Dr. Sharon Vila Wright: What You Should Know About the Houston OB-GYN

The Large Intestine: The Pouchy Path

The colon looks totally different. It has these distinctive pouches called haustra. In photos, they look like a series of rounded segments. This isn't just for show; these pouches help the colon move waste along while squeezing out every last drop of water. It’s basically a dehydration plant. If the photos show a smooth colon without those pouches, that can sometimes be a clinical sign of chronic issues like ulcerative colitis, sometimes referred to as a "lead pipe" appearance in imaging.

Why Doctors Need These Photos

Visual evidence is the gold standard in gastroenterology. You can have all the blood tests in the world, but nothing beats actually seeing the tissue.

- Polyp Identification: Most colon cancers start as small growths called polyps. In a colonoscopy photo, a polyp might look like a tiny mushroom or a flat, slightly discolored patch. Seeing them is the only way to remove them before they become a problem.

- Vascular Patterns: Doctors look at the "submucosal vascular pattern." Basically, they want to see the tiny blood vessels under the surface. If those vessels are blurry or missing, it’s a huge red flag for inflammation or edema.

- Diverticula: These look like small dark holes or "pockets" in the wall of the colon. They’re common as we age, but they can get infected. Seeing them on a screen helps a GI specialist decide how to manage your diet or medication.

Dr. Michael Gershon, often called the "father of neurogastroenterology," has spent decades talking about the "second brain" in our gut. When you look at these images, you aren't just looking at a pipe; you're looking at a massive nervous system. There are more neurons in your gut than in your spinal cord. That’s why your stomach "drops" when you’re nervous. Your intestines are literally "feeling" your emotions.

Misconceptions About Gut Health Visuals

Let’s be real for a second. The internet is full of "mucoid plaque" photos. You’ve seen them—people selling "detox" teas or "colon cleanses" showing these long, dark, rubbery ropes they claim came out of someone’s intestines.

Here’s the truth: That’s not a real thing.

👉 See also: Why Meditation for Emotional Numbness is Harder (and Better) Than You Think

Gastroenterologists who have performed thousands of colonoscopies will tell you they never see "mucoid plaque" stuck to the walls of the colon. The colon is a self-cleaning oven. It’s constantly shedding its lining and moving things along. Those "ropes" people see during cleanses are usually just the result of the cleansing product itself reacting with the water in the gut to create a gel-like substance. It’s a marketing trick.

When you see legitimate pictures of the colon and intestines, the walls are slippery and clean (assuming the patient did their prep right). There isn't decades-old "sludge" caked on the sides. If there was, the body wouldn't be able to absorb water, and you'd be in serious trouble very quickly.

Real "Scary" Stuff

What doctors actually worry about seeing are things like:

- Crohn’s Disease "Cobblestoning": This is exactly what it sounds like. The lining of the intestine looks like an old European street because of deep ulcers and swelling.

- Ischemic Colitis: This shows up as dark, purple, or even black tissue. It means the blood supply has been cut off. It’s a medical emergency.

- Pseudomembranous Colitis: This is usually caused by a C. diff infection. In photos, you’ll see yellowish-white plaques scattered all over the lining. It’s intense.

The Role of Technology in Modern Imaging

We’ve moved way beyond basic X-rays. Today, we have "pill cams" or capsule endoscopies. You swallow a camera the size of a large vitamin, and it takes thousands of photos as it travels through your entire digestive tract.

This has been a game-changer for the small intestine. Before this, the middle of the digestive tract was a "no man's land" because regular scopes couldn't reach it. Now, we can see every inch of that "velvet tunnel" in high definition.

✨ Don't miss: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

Then there’s Narrow Band Imaging (NBI). This is a special light filter that makes blood vessels look dark green and the surface of the tissue look bright. It’s like putting a "filter" on your gut to make cancer cells stand out. It’s incredible technology that helps doctors spot things that would be invisible under normal white light.

Seeing the Microbiome?

You can’t actually "see" the microbiome in standard pictures of the colon and intestines. Bacteria are too small. But you can see the results of a healthy or unhealthy microbiome. A healthy gut has a robust mucus layer. You can see this glistening in photos. This mucus is the home for your "good" bacteria. If that mucus is thin or the tissue underneath is raw, it’s a sign the ecosystem is out of balance.

Researchers like Dr. Justin Sonnenburg at Stanford have shown that when we don't eat enough fiber, our gut bacteria actually start eating that mucus lining for fuel. That's a visual you don't want: your own bacteria munching on your internal protection because they're starving for a salad.

Action Steps for Gut Health Visualization

If you’re looking at these images because you’re worried about your own health, don't play "Dr. Google" too hard. Self-diagnosing based on a photo you saw on a forum is a recipe for anxiety.

Instead, focus on what the visuals tell us about function.

- Hydrate for the Lining: That "glistening" look in healthy photos is mostly water and mucus. If you're chronically dehydrated, your colon has to work harder to pull water out of waste, which can lead to irritation.

- Fiber is the "Brush": While the colon doesn't need a "scrub," fiber provides the bulk that keeps those haustra (the pouches) working correctly. It’s like a workout for your gut muscles.

- Know the Warning Signs: You don't need a camera to know something is wrong. Changes in habits that last more than a few weeks, unexplained weight loss, or seeing red in the toilet are the "pictures" your body is sending you.

- Get the Scope: If you’re over 45 (or younger with a family history), get the colonoscopy. It’s the only way to get a definitive "picture" of your health. The prep is the worst part—the actual procedure is usually the best nap you'll ever have.

The human gut is an engineering marvel. It's a chemistry lab, a waste processing plant, and a nervous system all wrapped into one wet, pulsing tube. Looking at pictures of the colon and intestines should remind us that our bodies are incredibly complex. We aren't just what we eat; we are how we process, absorb, and protect ourselves from the outside world.

Take care of that inner lining. It’s the only one you’ve got, and it’s doing a lot of work behind the scenes to keep you upright.

Final Practical Moves

- Check your family history. If a relative had polyps or colon cancer, your "internal picture" matters sooner than most.

- Increase diverse fiber. Don't just stick to oatmeal. Your gut bacteria love variety—aim for 30 different plants a week.

- Monitor "Transit Time." Basically, how long it takes for food to go from the plate to the plumbing. Ideally, it's 12 to 48 hours. Too fast or too slow usually shows up as "ugly" visuals in clinical exams.