You’ve seen them. You know exactly what I’m talking about. You scroll through your feed and see a shot of a rusted steel bollard wall cutting through a desolate desert, or maybe a grainy thermal image of people moving through brush at midnight. Then, five minutes later, you see a drone shot of a vibrant, crowded beach in Tijuana where the fence just... stops in the ocean.

It’s weird. Pictures of the border of mexico are basically a "choose your own adventure" for political narratives. Depending on who is holding the camera, the 1,954-mile line looks like a war zone, a humanitarian crisis, or just a really long, expensive construction project.

The reality? It's all of that. But it's also a lot of things the news cameras usually miss because they aren't "dramatic" enough.

The Visual Identity of a 2,000-Mile Line

If you try to map out the visual history of the U.S.-Mexico border, you realize it isn't one single thing. It’s a patchwork. You have the older "landing mat" fences made from actual Vietnam-era helicopter landing strips—flat, rusted steel plates that look like they belong in a junkyard. Then you have the newer, 30-foot-tall "bollard" style fencing. These look like giant brown toothpicks stuck in the dirt. They were designed specifically so Border Patrol agents can see through them to the other side.

Most people don't realize how much the landscape dictates the photo.

In the Rio Grande Valley, the border is a river. It’s green. It’s lush. It looks like a place you’d go fishing, right up until you see the coils of concertina wire wrapped around the cypress trees. In the Arizona desert, near places like the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, the border is a straight line of steel that looks completely alien against the saguaros.

Honestly, it’s jarring.

What the Aerial Shots Don’t Show

Drone photography has changed everything. It gives us those sweeping, cinematic views of the wall snaking over mountains. But these "big picture" photos often sanitize the reality. They make the border look static.

📖 Related: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

When you get closer—I mean boots-on-the-ground close—the textures change. You see the "discarded" items. Backpacks. Water jugs painted black so they don’t reflect moonlight. Single shoes. These are the details that professional photographers like John Moore, who has covered the border for Getty Images for years, focus on to tell a human story. His famous photos aren't just about the architecture of the wall; they’re about the friction between the steel and the people.

There’s a specific type of photo that went viral a few years ago: the Pink Teeter-Totters.

Architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello installed neon pink seesaws through the slats of the border wall between Sunland Park, New Mexico, and Ciudad Juárez. It was only there for about forty minutes, but those pictures of the border of mexico changed the conversation. It showed that despite the massive physical barrier, the communities are still connected. Kids played with each other through the gaps. It made the wall look temporary and, frankly, a little bit ridiculous.

Why the Lighting Matters (Literally)

Have you noticed that most "crisis" photos are taken at dawn or dusk?

There’s a reason for that. Beyond just the "golden hour" being good for photography, that’s when the movement happens. The shadows get long. The high-contrast lighting makes the steel bollards look more imposing.

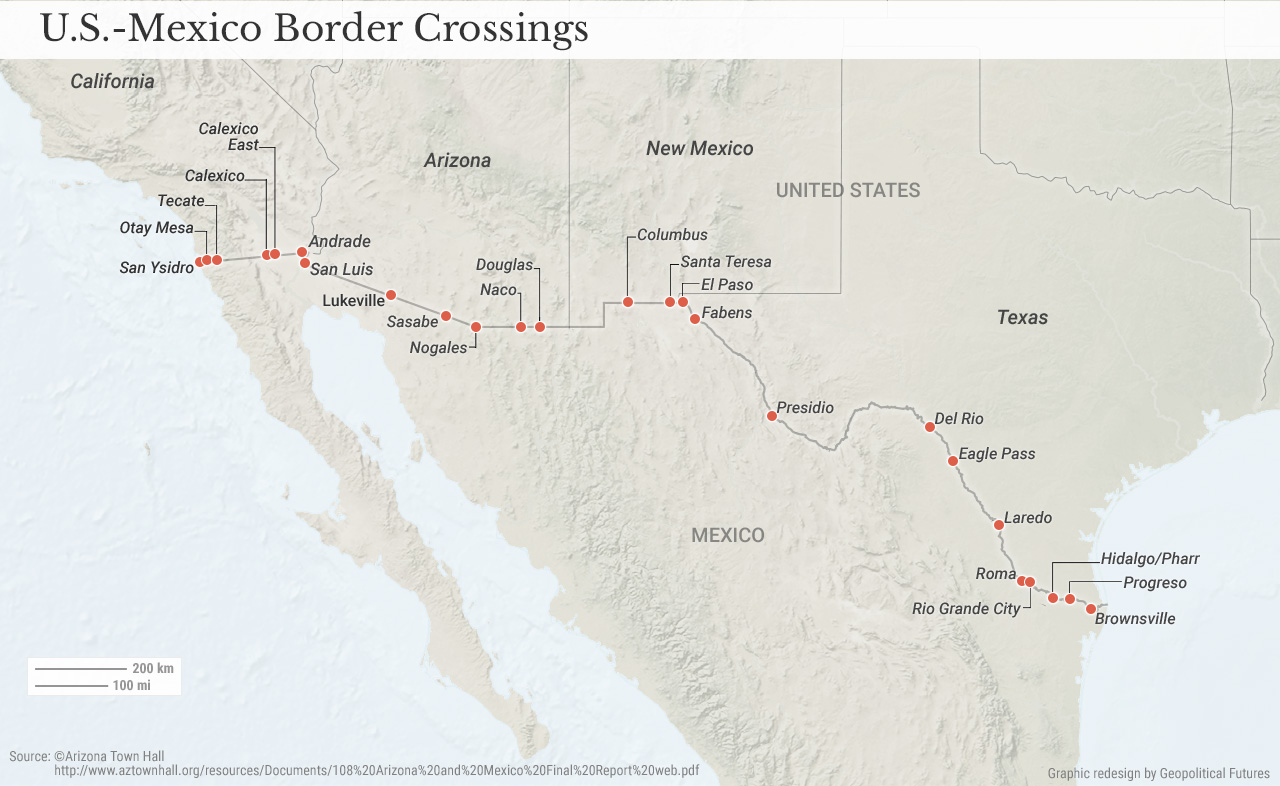

Compare that to the midday photos of the Port of Entry at San Ysidro. It’s the busiest land border crossing in the world. In those pictures, the border looks like a massive, bureaucratic parking lot. Thousands of cars, people selling churros between the lanes, and the dull gray of concrete. It’s not "scary" or "poetic"—it’s just exhausting. It’s the face of legal trade and daily commuting that rarely makes it into the "breaking news" segments.

The Conflict of Perspectives

Take the "International Boundary Marker" photos. There are 276 of these white obelisks stretching from El Paso to the Pacific. They were placed there after the Mexican-American War.

👉 See also: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

In the late 1800s, photos of these markers showed nothing but empty space. You could stand with one foot in each country and nobody cared. Today, those same markers are often trapped behind layers of secondary fencing or monitored by "autonomous surveillance towers." Seeing a photo of a 130-year-old stone monument dwarfed by a 30-foot steel wall is a pretty wild visual representation of how much the American psyche has shifted regarding security.

The Ethics of the "Border Photo"

There is a huge debate in the world of photojournalism about how to photograph people at the border. You’ve probably seen the photos of migrants in distress. Some people argue these images are necessary to provoke empathy and policy change. Others say they are exploitative, "poverty porn" that strips people of their dignity for the sake of a Pulitzer.

Magnum Photos and other high-end agencies have been trying to push for a more nuanced approach. Instead of just "the moment of capture," they’re looking for the "waiting."

The pictures of people waiting in camps in Matamoros or Tijuana tell a different story. It’s a story of boredom, laundry hanging on fences, and kids kicking a soccer ball in the dirt. It’s less "action-packed" than a river crossing, but it’s a more accurate depiction of what the border experience is like for 90% of the people there right now.

Misconceptions Captured on Film

One of the biggest misconceptions fueled by certain pictures is that the border is a continuous wall from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific. It isn't.

If you look at photos from the Tohono O’odham Nation in Arizona, you’ll see miles of "vehicle barriers"—basically big steel crosses that stop cars but allow animals (and people) to walk right through. The tribe has fought against a solid wall because it would bisect their ancestral lands. Photos from these areas show a much more porous, complicated reality than the "impenetrable barrier" narrative suggests.

The Role of Technology: Thermal and Night Vision

The most haunting pictures of the border of mexico aren't even taken with traditional cameras. They’re thermal.

✨ Don't miss: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

When you look at a thermal image, humans become glowing white ghosts against a cold, black background. It dehumanizes the subject by design—it’s technology built for detection, not for storytelling. Border Patrol uses these images to track heat signatures. When these images are leaked or shared in news reports, they reinforce the idea of the border as a high-tech battleground. It’s "predator vs. prey" imagery.

Then you have the "surveillance balloons" (aerostats). These white blimps hover over South Texas, and the photos taken from them are staggering. They can see for miles. From that height, the Rio Grande looks like a tiny ribbon, and the wall looks like a thin pencil line drawn in the sand.

Practical Realities for Photographers

If you’re a photographer headed to the border, you learn real quick that the rules are... flexible. You can photograph the wall from the U.S. side on public land, but the moment you point a lens at a Port of Entry, you’re going to have a very long conversation with a Customs and Border Protection officer.

There’s a weird tension. The border is one of the most photographed places on earth, yet it feels like one of the most misunderstood.

Real Examples of Border Visuals

- Friendship Park (San Diego/Tijuana): This is where families used to meet to touch pinkies through the mesh. Recent photos show the mesh has been replaced with thicker material, making even a finger-touch impossible.

- The "Floating Wall": In 2023, Texas installed orange buoys in the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass. The photos of these giant balls, some with "serrated saws" between them, sparked a massive legal fight. The visual was so aggressive it became a flashpoint for international relations.

- The Abandoned Bollards: In some parts of Arizona, there are photos of giant stacks of steel bollards just sitting in the desert, rusting. They were paid for but never installed after the construction was halted in 2021. They look like modern art ruins.

How to Read a Border Photo

Next time you see pictures of the border of mexico, don't just look at the subject. Look at the perspective.

- Check the Angle: Is it a low angle making the wall look massive? Or an aerial shot making the landscape look empty?

- Look for the "Gaps": The border isn't a straight line. Look for where the wall ends abruptly at a cliff or a riverbank. That's where the real story usually is.

- Identify the Source: An "official" government photo will look very different from a photo taken by a local resident in El Paso who just wants to show their backyard.

- Note the Surroundings: Is there a city in the background? Many people don't realize that El Paso and Juárez are essentially one giant city split by a fence. Photos that show the city lights of both countries together provide a context that "desert wasteland" photos lack.

The border is a moving target. It changes with the light, the weather, and the political administration in D.C. No single photo can capture it, but if you look at enough of them—the beautiful ones, the ugly ones, and the boring ones—you start to get a sense of what’s actually happening down there.

Actionable Insights for Following Border Developments:

Keep an eye on the Texas Tribune and High Country News for visual journalism that goes beyond the headlines. They often feature photo essays that spend weeks or months on a single stretch of land, providing the deep context that a 24-hour news cycle misses. If you're interested in the historical visual evolution, the Library of Congress digital collections have some of the earliest photos of the border markers from the 1890s, which offer a striking contrast to the high-tech barriers of 2026.