History is messy. It’s loud, it’s violent, and sometimes, it's just plain quiet in the most haunting way possible. When you start digging into pictures of slavery in africa, you aren't just looking at old ink on paper. You're looking at a crime scene that spanned centuries. Most people think they know the story. They think of the Trans-Atlantic route, the ships, and the American South. But the visual record tells a much more tangled story that includes the Indian Ocean trade, the Trans-Saharan routes, and the internal dynamics of the continent itself.

Honestly, it’s a lot to take in.

The camera wasn't even invented until the mid-19th century. This means we have a massive "blind spot" for the hundreds of years of slavery that happened before Louis Daguerre started messing around with silver plates. By the time photographers actually made it to the African coast or the interior, they weren't there to "document human rights." They were often there to justify colonialism or to show off "exotic" locales to people back in Europe. This bias is baked into almost every single image we have from that era. You have to read between the pixels—or the grain—to see what was actually happening to the people in the frame.

The Problem With Colonial Lenses and Pictures of Slavery in Africa

We need to talk about who was holding the camera.

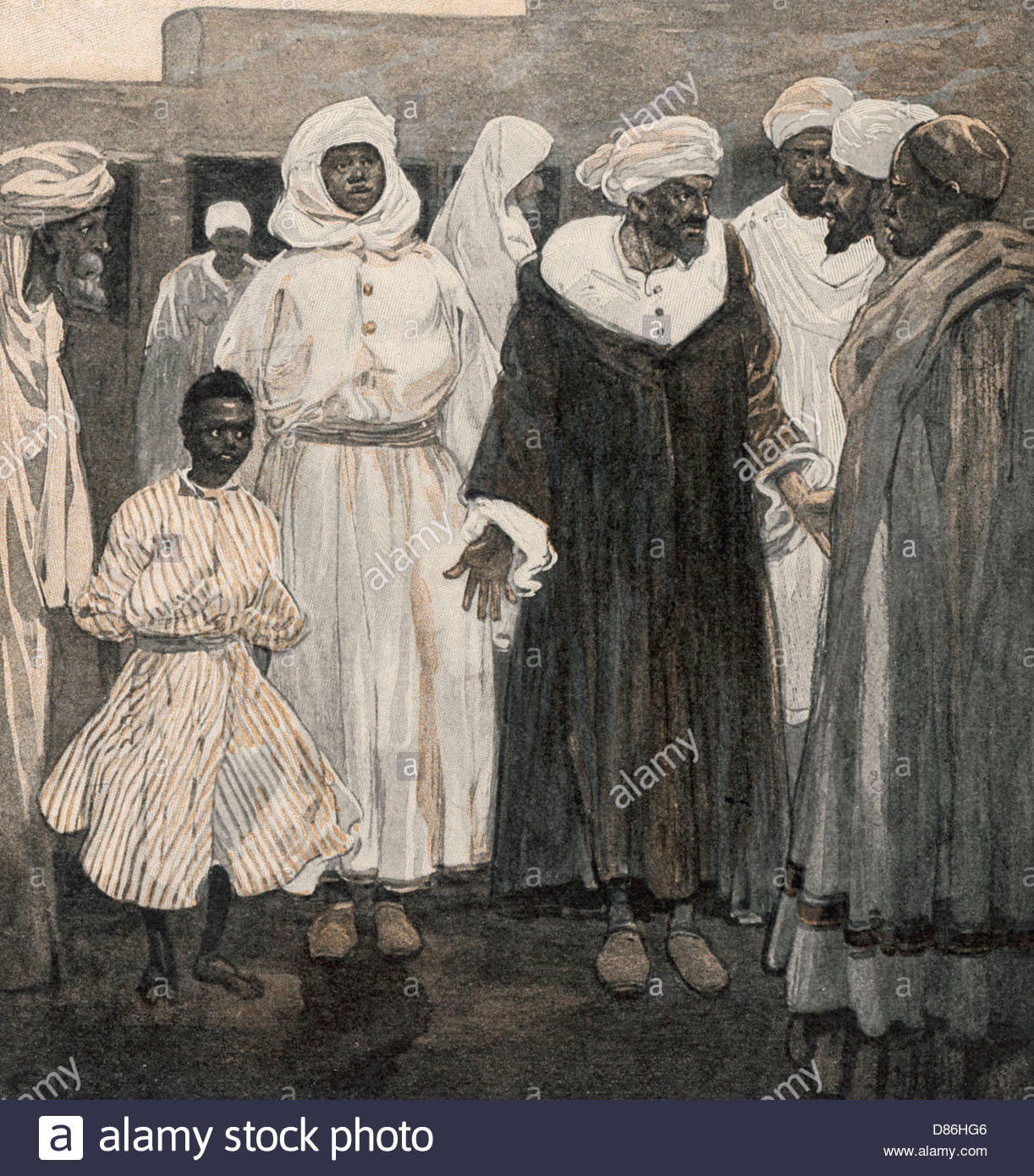

In the late 1800s, European missionaries and explorers like David Livingstone or Henry Morton Stanley were obsessed with "civilizing" the continent. When you see pictures of slavery in africa from this period, they are often framed to make the European look like a savior. Take the famous images of the Zanzibar slave market. Zanzibar was a massive hub for the East African slave trade, which sent people toward the Arabian Peninsula and India. The photos we have from there, often taken by British naval officers or missionaries, show people in chains, looking emaciated and broken.

The goal? To convince the public back in London that Britain needed to "intervene" and take over.

It’s a weird paradox. The photos are evidence of a real horror, but they were also used as propaganda for a different kind of control. You'll notice that the subjects rarely have names. They are just "Type of Slave" or "Captured Group." They are treated as objects twice: once by the slavers and once by the photographer.

What the Early "Snapshots" Don't Show

If you look at the archives in the Royal Geographical Society or the British Museum, you’ll find plenty of staged shots. Photographers would literally pose people to look more "savage" or more "submissive" depending on the narrative they wanted to sell. This makes the visual history of African slavery incredibly difficult to navigate. You’re always asking: Is this real, or is this what the photographer wanted me to see?

💡 You might also like: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

For example, photos of the "Dahomey Amazons"—the female soldiers of the Kingdom of Dahomey—often get lumped into discussions about African power dynamics. Some of these women were former slaves or captives who rose to power. But in photos, they are often depicted as "curiosities" for Westerners. The nuance of how internal African slavery worked—which was often very different from the racialized, chattel slavery of the Americas—is almost never captured in a single still image.

Seeing the East African Trade

Most Westerners are shocked when they see photos from the Indian Ocean trade. We’re so conditioned to think about the Atlantic. But the photos from the Red Sea and the Swahili Coast show a different reality. You’ll see images of dhows (traditional boats) packed with people, intercepted by the British Royal Navy’s "Anti-Slavery Squadron."

These pictures are gritty. They aren't the polished portraits of the Victorian era. They are often overexposed, blurry, and chaotic. You can see the ribs of the children. You can see the confusion in their eyes. These images were some of the first "humanitarian" photos ever taken. They were used to spark outrage, much like how social media is used today.

Captain George Sulivan of the HMS Daphne published several of these in his 1873 book. He didn't hold back. His photos of "liberated Africans" on the decks of British ships are some of the most visceral records we have. But even here, there’s a catch. Once "freed," many of these people were sent to "liberated African" settlements where they were essentially forced into indentured labor. The "freedom" in the photo wasn't always the freedom we imagine today.

Why the Absence of Photos is a Story Itself

Where are the photos of the Trans-Saharan trade? Basically, they don't exist.

The Sahara is a graveyard of history. Because the trade across the desert peaked long before the camera was portable or durable enough to survive the heat and sand, we rely on sketches and written accounts. This creates a "visual bias" in our education. We think the Atlantic trade was the "only" trade because that's where the most pictures are.

It’s a bit like that old saying: "The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence."

📖 Related: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

When you search for pictures of slavery in africa, you’re mostly seeing the tail end of a thousand-year-old system. You’re seeing the 1880s and 1890s. You aren't seeing the 1400s. You aren't seeing the height of the Songhai Empire or the early Portuguese raids. We have to use archaeology and oral traditions to fill those gaps, which is a lot harder than just scrolling through a digital archive.

The Congo and the "Kodak" Revolution

If you want to see the moment photography changed the world's mind, look at the Congo Free State under King Leopold II of Belgium. This wasn't "traditional" slavery in the sense of buying and selling people in a market, but it was a system of forced labor so brutal it defied description.

Alice Seeley Harris, a missionary, did something revolutionary. She took a Kodak brownie camera into the bush.

She took the photo of Nsala of Wala. In the picture, he is sitting on a porch, staring at the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter. It is, quite possibly, the most devastating photo ever taken in Africa.

This image didn't just "show" slavery or forced labor; it destroyed the Belgian King’s reputation. It proved that photos could be more than just souvenirs. They could be weapons. The "Congo Reform Association" used these pictures in lantern slide shows across America and Europe. People would faint in the audience. It was the first time the visual reality of African exploitation hit the "mainstream" in a way that couldn't be ignored.

The Ethics of Looking

Is it okay to look at these?

Some historians, like Saidiya Hartman, argue that we should be careful about "re-spectacularizing" black pain. When we look at pictures of slavery in africa, are we honoring the victims, or are we just voyeurs to their suffering? It’s a tough question. There’s a fine line between "witnessing" and "consuming."

👉 See also: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

Many modern museums in Africa, like the Maison des Esclaves on Gorée Island in Senegal, use these photos sparingly. They want you to feel the space—the cold stone, the "Door of No Return"—rather than just staring at a two-dimensional image of someone in chains. They want to restore the dignity that the original photographer often tried to strip away.

How to Research This Without Getting Overwhelmed

If you’re actually looking to study this, don't just use Google Images. It's a mess of mislabeled stuff. You’ll find photos from the 1920s labeled as 1850, or photos from India labeled as Africa.

Go to the source.

- The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture: They have an incredible digital collection that is properly vetted.

- The UNESCO "Slave Route" Project: They offer a lot of context that explains the why behind the images.

- The Anti-Slavery International Archives: They hold some of the oldest photographic records of human rights abuses.

Keep in mind that "slavery" as a term in 19th-century photography was often used loosely. Sometimes it referred to "domestic" servitude, which had different social rules in Africa compared to the plantation systems of the West. Other times, it was used by colonial powers as a "pretext" to invade a territory. They’d say, "Look, there is slavery here! We must colonize them to stop it!" even while they were setting up their own forced labor systems.

Actionable Steps for Deeper Understanding

If you want to move beyond just looking at the surface, here is how you should approach this history:

- Check the Metadata: If you find a photo online, try to find the original photographer. If it's an "anonymous" colonial photo, treat the caption with a grain of salt. The captions were often written by people who didn't speak the local language.

- Compare Regions: Don't look at "Africa" as one place. Compare photos from the West African coast (heavily influenced by the Atlantic trade) with those from the East (Zanzibar, Sudan, Ethiopia). The clothing, the chains, and the settings are totally different because the markets were different.

- Read the "Counter-Narrative": Look for photos taken by the first generation of African photographers in the late 19th century. They are rare, but they exist. They often show a much more complex side of life that wasn't just about victimhood.

- Support Local Archives: Many African nations are currently digitizing their own national archives. Following projects in Ghana, Nigeria, or Kenya will give you a much more authentic view than Western-centric databases.

The reality is that pictures of slavery in africa are uncomfortable because they are supposed to be. They represent a period where the human body was treated as a commodity, and the camera was often just another tool of that trade. By looking at them critically—by questioning the photographer and the motive—we stop being voyeurs and start being actual students of history. It’s not about just seeing the chains; it’s about understanding who put them there and how the people in those photos fought to get them off.