You're scrolling through a digital archive or maybe a textbook. You see a photograph of a newspaper clipping from 1924. Or perhaps it’s a high-res JPEG of a biography written in the 1970s. You might think, "Cool, I've got the evidence." But honestly, you’re looking at a copy of a copy. It’s a layer of separation that most people just ignore.

Pictures of secondary sources occupy a weird, liminal space in the world of information. They aren't the "real thing" (the primary source), but they aren't quite the original secondary document either. They’re a digital or physical ghost. Understanding why this distinction matters is basically the difference between being a casual reader and a sharp researcher.

What's actually happening when we use pictures of secondary sources?

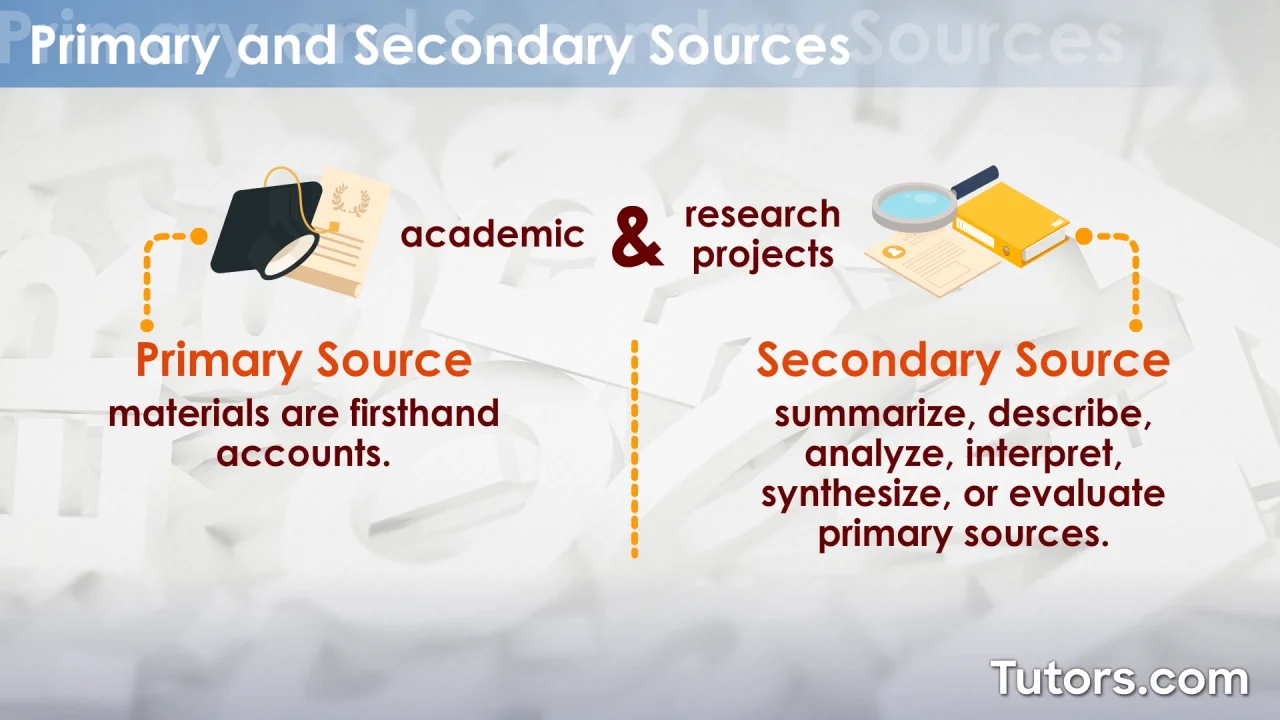

Let's get the terminology straight because it gets messy fast. A primary source is the raw data of history—a diary, a photograph of an event as it happened, or a raw data set from a lab. A secondary source is the analysis. It’s the history book, the documentary, or the peer-reviewed article written decades later. So, when you take a picture of that history book, you’ve created a tertiary visual artifact.

Why do we do it? Convenience. You can’t always lug a 500-page biography of Winston Churchill to the coffee shop. You snap a photo of page 212. Now you have a picture of a secondary source.

The problem starts when people treat these images with the same weight as a primary photograph. A photo of a map drawn in 1492 is a picture of a primary source. A photo of a map in a 2015 textbook—which was itself redrawn from an older map—is a different beast entirely. You're looking at someone else's interpretation of an interpretation, captured through your smartphone lens.

The resolution trap and the loss of context

Digital artifacts have a funny way of lying to us. When you look at high-quality pictures of secondary sources, the crispness of the text makes the information feel "truer." It’s a psychological trick. We equate visual clarity with factual accuracy.

🔗 Read more: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

But think about what’s missing.

When you photograph a page from a book, you lose the surrounding pages. You lose the citations at the bottom of the previous leaf. You lose the physical weight and the "feel" of the source, which, while it sounds flowery, actually provides vital context. Historians like Sam Wineburg, who leads the Stanford History Education Group, often talk about "sourcing" and "contextualization." If you only have a cropped image of a secondary source, you’ve basically blinded yourself to the author’s potential biases or the date the information was synthesized.

The danger of the "viral" screen grab

We see this on social media constantly. Someone posts a screenshot of a paragraph from an old textbook to "prove" a point about politics or science. That screenshot is a picture of a secondary source.

Usually, the person posting it hasn't read the whole chapter. They might not even know who the author is. Because it looks like a "real" page, it carries an air of authority that a text-based tweet doesn't have. It's persuasive. It's also incredibly easy to manipulate. You can crop out a "not" or a "however" and completely flip the meaning of the secondary analysis.

When these pictures are actually helpful

It's not all bad news. In fact, pictures of secondary sources are the backbone of modern accessibility in education.

💡 You might also like: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

Imagine a researcher in a rural library who needs access to a rare, out-of-print analysis held only at the Library of Congress. A digital picture of that secondary source is a lifeline. It democratizes knowledge. It allows for a level of collaboration that was impossible thirty years ago.

- Preservation: Books decay. Acidic paper from the mid-20th century turns yellow and brittle. A digital image preserves the secondary analysis before the physical object crumbles.

- Searchability: OCR (Optical Character Recognition) tech can "read" these pictures. Suddenly, a photo of a bibliography becomes a searchable database.

- Verification: If you’re arguing about what a specific scholar said in 1994, showing a picture of the exact page helps prevent "he-said-she-said" arguments.

How to use them without losing your mind (or your grade)

If you're using these images for a project, a blog post, or a dissertation, you have to be disciplined. You can't just drop a grainy photo of a book page into a document and call it a day.

First, look for the metadata. If you’re taking the picture yourself, take a photo of the title page and the copyright page first. This ensures you always know the "who, what, and when" of the secondary source.

Second, check the edges. Are you cutting off footnotes? In academic writing, the footnotes are often more important than the main text. That’s where the secondary source points back to the primary source. If your picture of a secondary source doesn't include the citations, it's basically useless for serious verification.

The ethics of sharing secondary imagery

There’s a copyright element here that gets skipped. Just because you took a photo of a page in a book doesn’t mean you own the rights to that image. The author of the secondary source owns the copyright to the text, and the publisher often owns the rights to the layout and typography.

📖 Related: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

Sharing pictures of secondary sources on a large scale—like a public website—can get you into hot water. Fair use usually covers a small snippet for critique or education, but don't go posting entire chapters. It’s not just about the law; it’s about respecting the labor of the person who did the original synthesis.

Moving beyond the screen

We live in an era where "seeing is believing," but pictures of secondary sources should be treated with a healthy dose of skepticism. They are tools, not end-points.

If you find a compelling argument in a photo of a book, your next step should always be to find the digital text version or the physical book itself. Check the bibliography. See what primary sources the author used to reach their conclusion.

Actionable Insights for Better Research:

- Document the "Source of the Source": Every time you save a picture of a secondary source, rename the file immediately with the Author, Date, and Page Number. "IMG_4302.jpg" is where information goes to die.

- Verify with OCR: Use tools like Google Lens or Adobe Acrobat to pull the text out of the image. This allows you to cross-reference the quotes against other digital libraries like Google Books or JSTOR to ensure the text hasn't been altered.

- Look for the Full Spread: When photographing a secondary source, try to capture both the left and right pages. The headers and footers often contain the chapter title or section name, which provides essential context for the paragraph you're focusing on.

- Prioritize Primary: Always ask, "Can I get closer to the original?" If the picture of the secondary source mentions a specific 19th-century census, go look for the census itself. Use the secondary source as a map, not the destination.

- Check for Editions: Secondary sources are often updated. A picture of the 1982 edition of a textbook might contain "facts" that were debunked in the 2010 edition. Always check if you're looking at the most recent synthesis of the information.

Don't let the convenience of a digital image make you a lazy thinker. These pictures are gateways. Use them to open the door, but make sure you actually walk through it.