Pluto is weird. For decades, we thought it was just a frozen, dead marble at the edge of the solar system, a lonely rock that didn't do much of anything besides circle the sun in a weird, tilted orbit. Then 2015 happened. When NASA's New Horizons spacecraft screamed past the dwarf planet at 36,000 miles per hour, it sent back pictures of Pluto surface that basically broke planetary science for a few months.

It wasn't a cratered wasteland. Not even close.

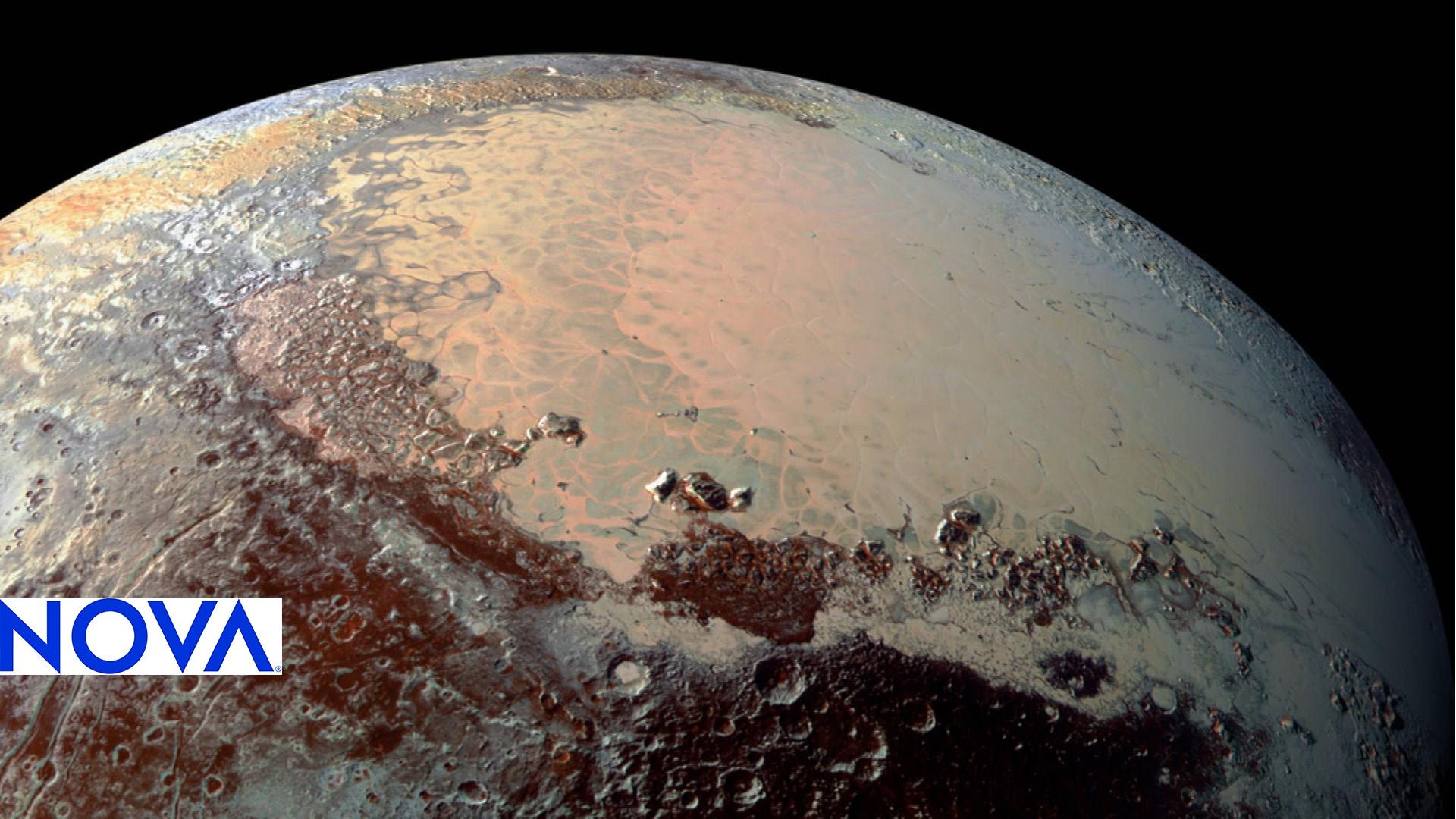

Instead, we saw towering mountains made of solid water ice and vast, smooth plains of frozen nitrogen that look like they're still "breathing." Honestly, it’s a bit unsettling how active it is. If you look at the high-resolution imagery, you're not just looking at a map; you're looking at a geological engine that shouldn't be running.

The Heart That Actually Beats

The most famous feature in these pictures of Pluto surface is Tombaugh Regio. You probably know it as "the heart." But the left lobe of that heart, specifically Sputnik Planitia, is the real star of the show.

It’s a massive basin filled with nitrogen ice. Because nitrogen is soft and squishy compared to water ice, it behaves like a slow-motion lava lamp. Heat from Pluto’s interior—likely leftover from its formation—causes the nitrogen to rise, cool, and sink back down. Scientists like Alan Stern, the principal investigator for New Horizons, have pointed out that this surface is incredibly young. We’re talking less than 10 million years old. In geological terms, that’s yesterday.

There are no craters in Sputnik Planitia. None. That means something is constantly "repaving" the ground. Imagine a world so far from the sun that the "rocks" are actually water ice and the "glaciers" are made of the stuff we breathe on Earth.

Why the Colors Look Like a Filter

If you've seen the "true color" vs "enhanced color" images, you might feel a bit cheated. The psychedelic purples and greens in some NASA releases aren't what you'd see if you were standing there. But the real colors are arguably cooler. Pluto is surprisingly red.

This reddish-brown tint comes from tholins. These are complex organic molecules created when ultraviolet light and cosmic rays hit methane in Pluto's atmosphere. They rain down like a subtle, rusty soot. It’s a chemical process that suggests Pluto is far more "organic" than we ever gave it credit for.

Cryovolcanoes: When Ice Acts Like Lava

One of the most mind-bending things about the pictures of Pluto surface is Wright Mons. It’s a mountain about 90 miles across and 2.5 miles high. But it’s not a normal mountain. It has a giant hole in the middle.

Most researchers believe this is a cryovolcano. Instead of molten rock, it likely spewed a slushy mix of water ice, ammonia, or methane. Think of it as a cosmic Slurpee machine on a planetary scale. The sheer volume of material required to build Wright Mons suggests that Pluto’s interior was much warmer for much longer than anyone’s models predicted.

It challenges the "dead rock" theory. If a tiny ball like Pluto can stay warm enough to have volcanoes, what does that mean for other objects in the Kuiper Belt? We might be looking at a whole neighborhood of geologically alive worlds.

The Blue Haze and Floating Mountains

If you look at the "backlit" photos taken as New Horizons looked back at the sun, you see a distinct blue ring around Pluto. That’s the atmosphere. It’s thin, but it’s organized into distinct layers of haze.

📖 Related: The Generative AI News 2025 Updates That Actually Matter

Beneath that haze, you have the Al-Idrisi mountains. These are jagged, chaotic peaks of water ice. What’s crazy is that they appear to be floating. Since water ice is less dense than the nitrogen ice in the plains, these "mountains" are essentially icebergs. They drift and jostle over millions of years. It’s a dynamic landscape that feels more like an ocean than a planet.

The Scale of the Mystery

We only have high-resolution data for about 40% of the planet. The rest? It’s a blur. We saw enough to know we were wrong about almost everything, but not enough to solve the puzzles. For example:

- The "Blades" of Tartarus Dorsa: These are giant shards of methane ice, some as tall as skyscrapers. We think they form through sublimation—turning directly from solid to gas—but the precision of the shapes is baffling.

- The Possible Subsurface Ocean: The way Pluto wobbles and the cracks on its surface suggest there might be a liquid water ocean buried deep beneath the ice.

- The Dunes: There are ripples in the sand... except the sand is made of solid methane grains. Wind on Pluto is incredibly weak, yet somehow it moves these particles into organized patterns.

How to Explore Pluto Digitally

If you want to see these pictures of Pluto surface for yourself without the filtered "pop science" layers, you have to go to the source. NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS) is where the raw files live.

- Check the Raw Images: Search the New Horizons LORRI (Long Range Reconnaissance Imager) archives. These are black and white, grainy, and raw. They show you exactly what the camera saw before the artists got ahold of them.

- Use Google Mars (Wait, what?): Surprisingly, Google has a Pluto mode in some versions of its mapping software that overlays New Horizons data onto a 3D sphere.

- Follow the Scientists: People like Dr. Alex Parker and Dr. Anne Verbiscer often share re-processed versions of these images on social media, bringing out details that the original 2015 releases missed.

What's Next for the Dwarf Planet?

There is currently no mission on the books to go back to Pluto. New Horizons was a flyby; it’s now billions of miles away in the deep Kuiper Belt. Any new pictures of Pluto surface will have to come from a future orbiter, which is a project that would take decades to fund and launch.

Until then, we are stuck staring at the 2015 data. But that’s not a bad thing. Every year, new techniques in image processing allow us to see deeper into the shadows of the Cthulhu Macula or understand the grain size of the nitrogen frost.

To truly appreciate what you're looking at, stop thinking of Pluto as a "lesser" planet. Think of it as a chemical laboratory. It’s a place where the temperature is so low that the rules of geology change. Water is the rock, nitrogen is the fluid, and methane is the sand. It’s an inverted world.

The best way to stay updated on new findings is to keep an eye on the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI). They are the hub for New Horizons data analysis. You can also monitor the ArXiv.org planetary science section for new papers that re-evaluate the surface features based on more recent atmospheric modeling.

Don't just look at the pictures; look at the shadows. They tell you the height of the peaks and the depth of the canyons. Every pixel is a piece of a puzzle that we’re still trying to put together.

Actionable Insight: To get the most "real" experience of Pluto, seek out the "Pluto: En route to the Heart of the Kuiper Belt" technical maps provided by the USGS. These maps name the features—craters named after explorers, plains named after mythological underworlds—and provide a sense of scale that a simple JPEG cannot convey. Studying the topographic maps alongside the photos helps you realize that the "Heart" isn't just a shape; it's a massive, deep depression that fundamentally changes how the planet rotates.