You’re scrolling through Google because your knuckles look... different. Maybe they're thicker. Maybe that index finger is starting to tilt slightly toward your thumb like a leaning tower of bone. You've probably seen those clinical pictures of osteoarthritis in the fingers—the ones with the red circles and the scary-looking bumps. It's enough to make anyone panic. But honestly? Those photos are often the "worst-case scenarios" that doctors use in textbooks.

Your hands are your life. You use them to type, to cook, to hold your kid's hand, or to scroll through this very article. When they start to change, it’s personal. Osteoarthritis (OA) is basically the "wear and tear" version of arthritis, where the protective cartilage on the ends of your bones wears down over time. It’s the most common form of arthritis, affecting millions. Yet, looking at a static image of a gnarly knuckle doesn't actually tell you how much pain someone is in or how well they can still move.

What You’re Actually Seeing in Those Pictures of Osteoarthritis in the Fingers

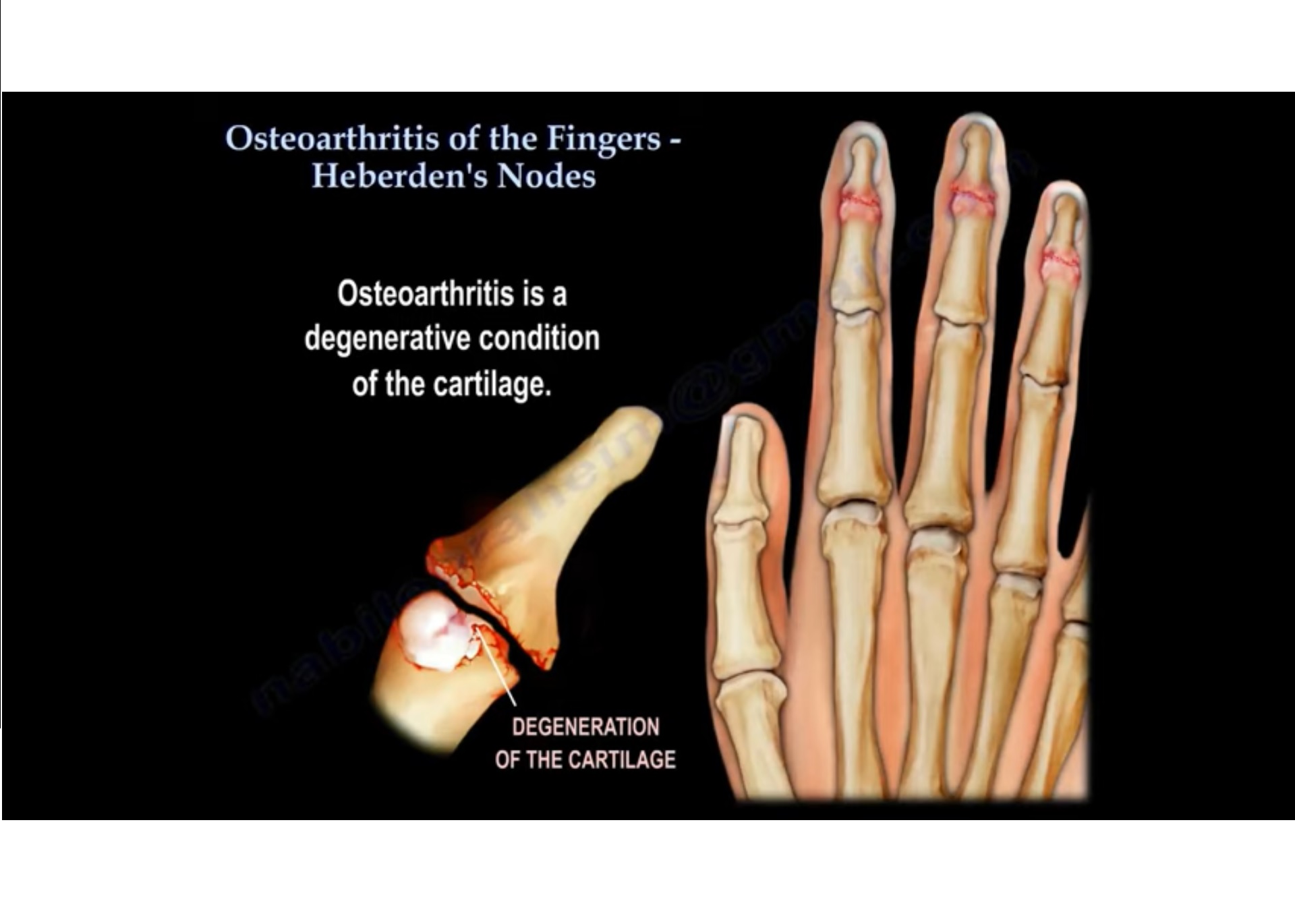

When you look at a photo of an osteoarthritic hand, the first thing that jumps out is the swelling. But it’s not just "puffiness." In OA, we’re often looking at Heberden’s nodes and Bouchard’s nodes.

Heberden’s nodes are those hard, bony bumps that show up on the joint closest to the fingernail (the DIP joint). If the bump is on the middle joint of the finger, it’s a Bouchard’s node. These aren't just fluid; they are actual bone spurs, or osteophytes. Your body is trying to "fix" the loss of cartilage by growing more bone. It’s a bit of a clumsy repair job by your immune system.

Sometimes the finger looks crooked. This is called joint malalignment. As the cartilage disappears unevenly, the joint can start to collapse on one side more than the other. This creates that "zigzag" appearance you see in advanced medical photography. It looks painful. Surprisingly, for some people, it’s more of a dull ache or a stiffness that’s worse in the morning.

The Thumb Base: The Most Overlooked Area

Don't just look at the fingers. Look at the base of the thumb.

Basal joint arthritis (or CMC arthritis) is incredibly common. In photos, you might notice a "squared off" appearance at the bottom of the hand near the wrist. This happens because the thumb is the most mobile part of your hand, and that constant pivoting wears down the trapeziometacarpal joint faster than almost any other spot. If you find it hard to turn a key or open a pickle jar, this is likely the culprit.

🔗 Read more: In the Veins of the Drowning: The Dark Reality of Saltwater vs Freshwater

Why the Photos Can Be Deceptive

Here is a truth most doctors don't lead with: X-rays and photos don't always match your pain level.

You could have a hand that looks perfectly normal in a photograph but feels like it's being squeezed in a vice. Conversely, some people have hands with massive, visible Heberden’s nodes and they can still play the piano or garden for hours without a single wince. This is the "radiographic vs. clinical" gap.

A study published in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases pointed out that many people with significant radiographic evidence of OA (the "bad" pictures) report very little functional limitation. Why? Because the body is incredibly adaptable. We find "workarounds." We use our palms more, we change our grip, or our nervous system just gets used to the structural changes.

The Color Matters (Sometimes)

In many pictures of osteoarthritis in the fingers, you'll notice the skin might look shiny or slightly red over the joint. This indicates an active inflammatory phase. OA isn't always "cold" wear and tear; it can have "hot" periods where the joint lining (synovium) gets irritated.

If the joint looks purple or extremely swollen and feels hot to the touch, that might not be simple OA. That could be gout or rheumatoid arthritis (RA). While OA is about bone-on-bone, RA is an autoimmune attack on the joint lining. The photos look different because RA usually hits the knuckles where the fingers meet the hand (the MCP joints), whereas OA loves the tips and the middle joints.

Real-Life Examples: What It Looks Like Over Time

Think of OA as a slow-motion movie.

💡 You might also like: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

- Stage 1: The "Maybe I Just Overdid It" Phase. No visible bumps in pictures yet. Maybe just a bit of stiffness after a long day of yard work.

- Stage 2: The First Bumps. You notice a tiny, hard lump on your index finger. It doesn't hurt much, but your ring feels tighter.

- Stage 3: Visible Deviation. This is where the pictures of osteoarthritis in the fingers start to look like the ones online. The finger might tilt a few degrees. Gripping a pen becomes slightly awkward.

- Stage 4: Bone on Bone. The space in the joint is almost gone. The bumps are prominent. Movement is limited, but interestingly, sometimes the pain decreases because the joint has effectively "fused" itself.

Gender and Genetics Play a Huge Role

If your mom had "knobby" fingers, there is a very high chance you will too. Women are significantly more likely to develop hand OA than men, especially after menopause. Estrogen seems to have a protective effect on cartilage, so when those levels drop, the "buffer" in your joints can thin out more rapidly.

Dr. Kim Bennell, a researcher at the University of Melbourne, has spent years looking at how we manage this. The focus is shifting away from "fixing the look" of the hand to "fixing the function."

Modern Treatments: Beyond Just Staring at the Bumps

If your hands look like those pictures of osteoarthritis in the fingers, what do you actually do? You don't just sit there and wait for them to get worse.

- Hand Therapy is a Game Changer.

A specialized hand therapist can teach you "joint protection" techniques. This sounds fancy, but it basically means learning how to use your hand without putting all the stress on the tiny joints. For example, using a thick-handled pen instead of a skinny one. Or carrying a grocery bag over your forearm instead of gripping the handles with your fingers. - Topical NSAIDs.

Instead of swallowing pills that can mess with your stomach, many doctors now recommend topical Diclofenac (Voltaren gel). You rub it directly on the knuckles. It gets to the joint without traveling through your whole system. - Paraffin Wax Baths.

It sounds like a spa treatment, and it kind of is. Dipping your hands in warm wax provides a deep, moist heat that can loosen up stiff joints and make them look less "inflamed" in the short term. - Splinting.

Especially for the thumb, a small, low-profile splint can stabilize the joint while you’re working, preventing that "grinding" sensation.

The Role of Diet

While no "magic fruit" will cure arthritis, inflammation is global. Eating a Mediterranean-style diet—high in Omega-3s from fish and antioxidants from berries—can't hurt. There's some evidence that people with lower systemic inflammation feel less "flares" in their hands.

Surgery: The Last Resort

Most people with hand OA never need surgery. It’s not like a hip or a knee replacement. However, if the pain is truly unbearable, surgeons can perform a "joint fusion" (making the joint solid so it doesn't move and thus doesn't hurt) or even an arthroplasty (replacing the joint with a small implant). But honestly, most people find relief through lifestyle changes and physical therapy.

How to Self-Assess Using Your Own "Pictures"

Take a photo of your hands flat on a table. Do it once every six months.

📖 Related: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

Look for:

- New bumps at the very tips of the fingers.

- Increased "squaring" at the base of the thumb.

- Any finger that is starting to drift toward its neighbor.

If you see these changes, don't freak out. Seeing pictures of osteoarthritis in the fingers on your own hands is just a signal to start being nicer to your joints. It doesn't mean you'll lose the use of your hands. It just means the "equipment" is wearing in.

Actionable Steps for Better Hand Health

Stop trying to "crack" your knuckles to relieve the stiffness; it doesn't help the cartilage. Instead, start a daily routine of gentle range-of-motion exercises. "Make a fist, then straighten." Repeat it ten times while you're watching TV.

Switch out your kitchen tools. If you have those old-school manual can openers that require a tight grip and a twisting motion, throw them away. Get an electric one. Buy "easy-grip" versions of vegetable peelers. These small changes reduce the daily mechanical load on your joints significantly.

Check your Vitamin D levels. There is some clinical evidence suggesting that Vitamin D deficiency can make the progression of OA feel more painful. It's a simple blood test your doctor can run.

Lastly, focus on grip strength, but do it safely. Using a soft "stress ball" is better than those heavy-duty spring-loaded grippers. You want to keep the muscles strong to support the bones, but you don't want to crush the remaining cartilage in the process.

Your hands have done a lot of work for you. If they're starting to show the signs of that work, it's not a disaster—it's just a new phase of maintenance. Focus on how they feel and how they function, rather than how closely they match a medical photo.

Next Steps for Relief:

- Invest in "Adaptive Tools": Look for kitchen and office supplies labeled "ergonomic" or "easy-grip."

- Apply Heat: Use a heating pad or warm water soak for 10 minutes every morning to reduce "morning stiffness."

- Consult a Professional: Ask your primary doctor for a referral to a Certified Hand Therapist (CHT) for a custom exercise plan.

- Monitor for Flares: Keep a log of what activities cause the most pain and adjust your technique accordingly.