You’ve probably seen them. Those hyper-detailed anatomical diagrams or glossy pictures of muscles in the leg that make the human body look like a perfectly organized roadmap. They’re everywhere—plastered on gym walls, tucked into medical textbooks, and floating around Instagram with "leg day" hashtags. But honestly? Most of those images are kinda misleading. They give you the "what" without ever explaining the "how" or the "why," leaving a lot of people scratching their heads when they actually try to feel those muscles working during a squat or a long run.

Your legs are a messy, beautiful architectural marvel.

They aren't just blocks of meat stacked on top of each other. It’s a complex web of fascia, nerves, and tendons. When you look at pictures of muscles in the leg, you’re usually seeing a "clean" version. Prosectors in a lab have spent hours scraping away the connective tissue just to make those muscles visible for the camera. In reality, it’s all much more intertwined. If you want to actually understand your lower body—whether you're rehabing an injury or just trying to get stronger—you have to look past the surface-level aesthetics.

What You’re Actually Seeing in Pictures of Muscles in the Leg

Most people start at the front. The quadriceps. "Quad" means four, so you’re looking at four distinct muscles: the rectus femoris (the big one in the middle), the vastus lateralis (on the outside), the vastus medialis (the "teardrop" near your knee), and the vastus intermedius which hides underneath the others.

But here is the thing.

The rectus femoris is the only one of the four that crosses both the hip and the knee joint. That’s a huge detail. Most pictures of muscles in the leg show it as just a knee extender. But it’s a hip flexor too. If you’re sitting at a desk all day, that muscle is stuck in a shortened position. It’s tight. It’s cranky. And because it’s a "two-joint" muscle, its tightness can pull your pelvis into an anterior tilt, causing back pain that you’d never guess started in your thigh.

Then you flip the leg over. The hamstrings.

People talk about "the hamstring" like it’s one stringy muscle. It’s not. It’s a group of three: the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. If you look at high-quality anatomical pictures of muscles in the leg from the back, you’ll see they actually fan out. They don’t just run straight up and down. They help rotate your lower leg when your knee is bent. It’s why some people feel a "pull" on the inside of their leg versus the outside. They aren't just ropes; they’re steering cables.

The Mystery of the Deep Posterior Compartment

Let’s talk about the stuff nobody sees.

🔗 Read more: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

Deep under your big calf muscle—the gastrocnemius—lies the soleus. In most pictures of muscles in the leg, the soleus looks like a flat pancake. But it’s actually the powerhouse of endurance. While the "gastroc" is for explosive jumping, the soleus is what keeps you upright while you walk. It’s almost entirely slow-twitch fibers.

And then there's the popliteus. It’s a tiny, diagonal muscle behind the knee. You’ll barely notice it in a standard diagram.

It’s the "key" that unlocks the knee.

Literally. To bend your leg from a straight position, the popliteus has to rotate the femur slightly to unlock the joint. If you have "unexplained" deep knee pain, it’s often this little guy acting up, not the big muscles you see in the posters.

Why 3D Renders Might Be Better Than Photos

If you’ve ever looked at a real cadaver photo versus a 3D medical render, the difference is jarring. 3D pictures of muscles in the leg are great for learning names. They use bright colors to separate the adductors (your inner thighs) from the abductors (the glute medius and minimus on the side).

Real life isn't color-coded.

In a real human leg, the adductor magnus is so massive it’s sometimes called the "fourth hamstring." It’s a huge, meaty slab of muscle that plays a massive role in hip extension. Most "beginner" pictures of muscles in the leg don't show just how much space the adductor magnus takes up. It’s a powerhouse. If you only train your hamstrings and ignore your adductors, you're leaving a lot of strength on the table.

You’ve gotta think about the layers.

💡 You might also like: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

- Superficial Layer: The stuff you see in a mirror (Quads, Gastroc, Glute Max).

- Intermediate Layer: The stabilizers (Soleus, Hamstrings).

- Deep Layer: The stuff that actually keeps your joints from falling apart (Popliteus, Tibialis Posterior, Adductor Brevis).

The Misunderstood Lower Leg

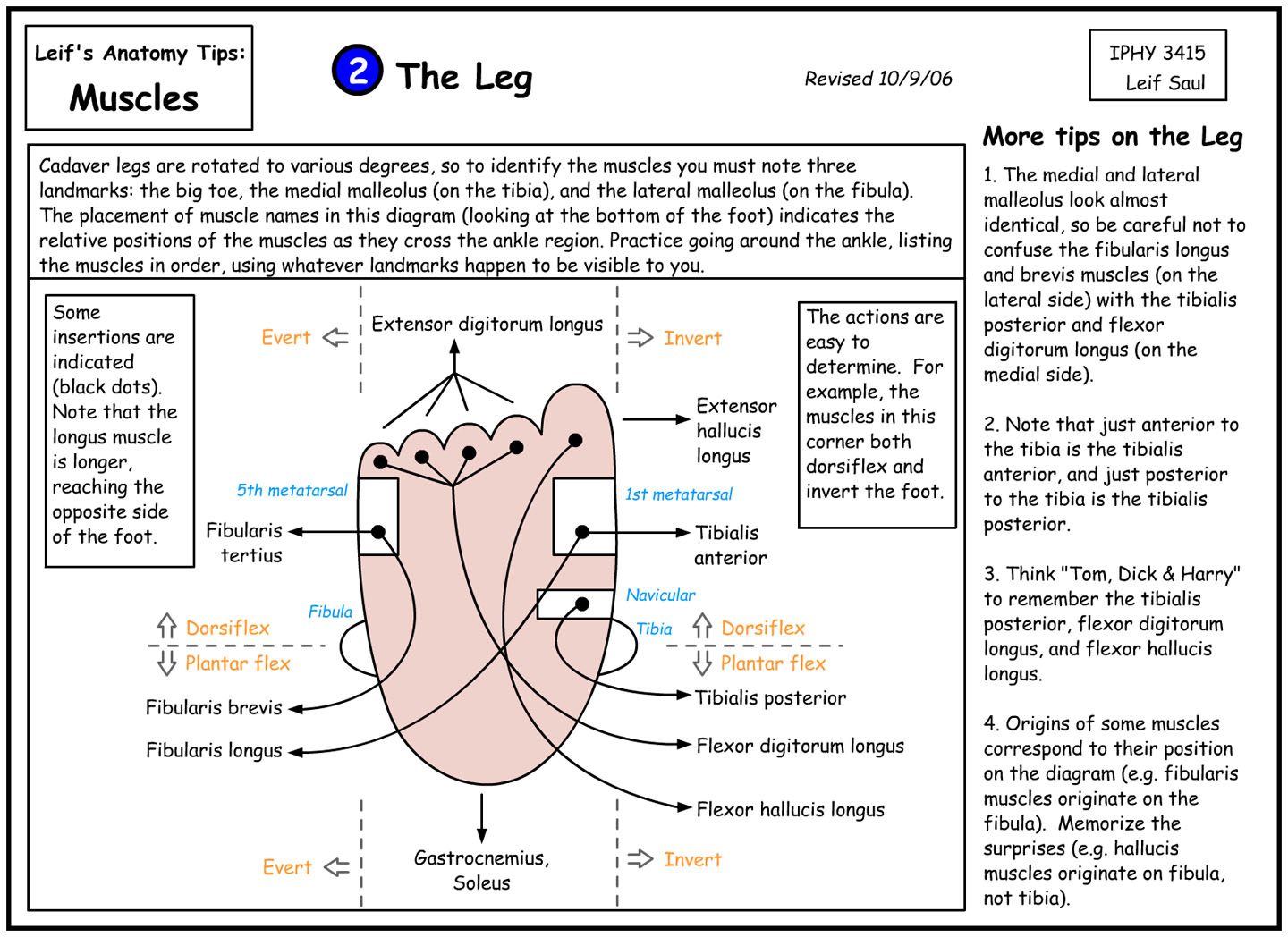

Most people focus on the thigh, but the lower leg is where the real mechanical magic happens. Look at pictures of muscles in the leg focusing on the "anterior compartment." You’ll see the tibialis anterior. It’s that strip of muscle right next to your shin bone.

Ever had shin splints?

That’s usually the tibialis anterior—or its neighbor, the extensor digitorum longus—screaming for help. These muscles are responsible for "dorsiflexion," or pulling your toes toward your shin. We spend so much time focusing on the calf (pushing down) that we completely forget the muscles that pull up. When these are weak, your gait changes. You start slapping your feet on the ground. Your knees take more impact.

It’s all connected.

On the lateral side (the outside of the shin), you have the peroneals (also called the fibularis muscles). In most pictures of muscles in the leg, they look like thin little ribbons. But they are the primary defenders against ankle sprains. They pull the foot outward. If you’ve ever rolled your ankle, these are the muscles that failed to react fast enough. Training them isn't about "getting big," it's about not ending up in a walking boot.

Variation in Human Anatomy

Here is something the textbooks won't tell you: your leg doesn't look like the picture.

Dr. Gil Hedley, a famous "somanaut" and fascia researcher, often points out that internal anatomy varies just as much as external features. Some people have "high" calf insertions, where the muscle belly is short and the tendon is long (great for sprinting). Others have "low" insertions, where the muscle goes almost all the way to the ankle.

Some people are missing certain muscles entirely!

📖 Related: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

The plantaris is a tiny, vestigial muscle with a long tendon that runs down the back of the leg. About 10% of the population doesn't even have one. In some pictures of muscles in the leg, it’s featured prominently; in others, it’s ignored. If you’re looking at an image and thinking, "My leg doesn't feel like it’s shaped that way," you might actually be right.

How to Use These Pictures for Better Training

Don't just stare at the image. Use it to build a mind-muscle connection.

When you’re looking at pictures of muscles in the leg specifically showing the gluteus medius, notice where it attaches—the top of your femur (thigh bone). It pulls the leg away from the center of the body. So, next time you’re doing side-lying leg raises, don't just move your leg. Visualize that specific muscle shortening.

It sounds "woo-woo," but it works.

Studies in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research have shown that internal focus (thinking about the muscle) can increase EMG activity. You’re literally turning the muscle "on" more effectively because you know where it lives.

Common Misconceptions Found in Visual Aids

- The IT Band is a muscle. It’s not. It’s a thick band of fascia. You can’t "stretch" it like a muscle, no matter what the foam roller enthusiasts tell you. You have to work the muscles attached to it, like the Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL).

- The "Teardrop" is a separate muscle. It’s just the lower part of the vastus medialis. You can't "isolate" it completely, though certain ranges of motion (the last 15 degrees of extension) hit it harder.

- Calves are just one muscle. As we discussed, the Gastroc and Soleus are different. If you do calf raises with straight knees, you hit the Gastroc. Bend your knees? Now you’re hitting the Soleus.

Actionable Steps for Better Leg Health

Stop just looking and start feeling. Here is how you actually apply this anatomical knowledge:

- Self-Palpation: Find a diagram of the leg. Now, try to find those muscles on your own body. Can you feel the tendon of your hamstrings behind your knee? There should be two on the inside and one on the outside.

- Differentiate Your Calf Work: If you want better-looking (and stronger) lower legs, you must perform calf raises with both straight and bent knees.

- Balance Your Shin: If you do 100 calf raises, do 50 toe raises (lifting your toes toward your shins). This balances the tension around the tibia and can prevent shin splints.

- Release the TFL: Look at a picture to find your "hip bone" (the ASIS). Drop down and slightly outside. That’s your TFL. If your knees hurt, try massaging this spot instead of the knee itself.

Understanding pictures of muscles in the leg is about more than memorizing names for a biology quiz. It’s about understanding the leverage and the pulleys that allow you to walk, jump, and dance. Next time you see a diagram, look for the overlaps. Look for the way the muscles wrap around the bone. That's where the real power is.