You’ve probably seen them. Those neon-green tails and sticky-looking toes. They’re everywhere lately. Honestly, it’s not just a coincidence that pictures of lizards and geckos are suddenly the internet's favorite aesthetic.

We used to be obsessed with cats. Then it was the "golden retriever energy" era. But now? We’ve moved on to the scaled, the bug-eyed, and the surprisingly charismatic world of reptiles. It's weird. It's also incredibly fascinating.

If you spend five minutes on Instagram or Reddit's r/herpetology, you’ll realize people aren't just taking blurry snapshots of garden skinks anymore. We are talking high-definition macro photography that makes a Crested Gecko look like a tiny dragon from a high-budget fantasy film.

The Science Behind the Scute

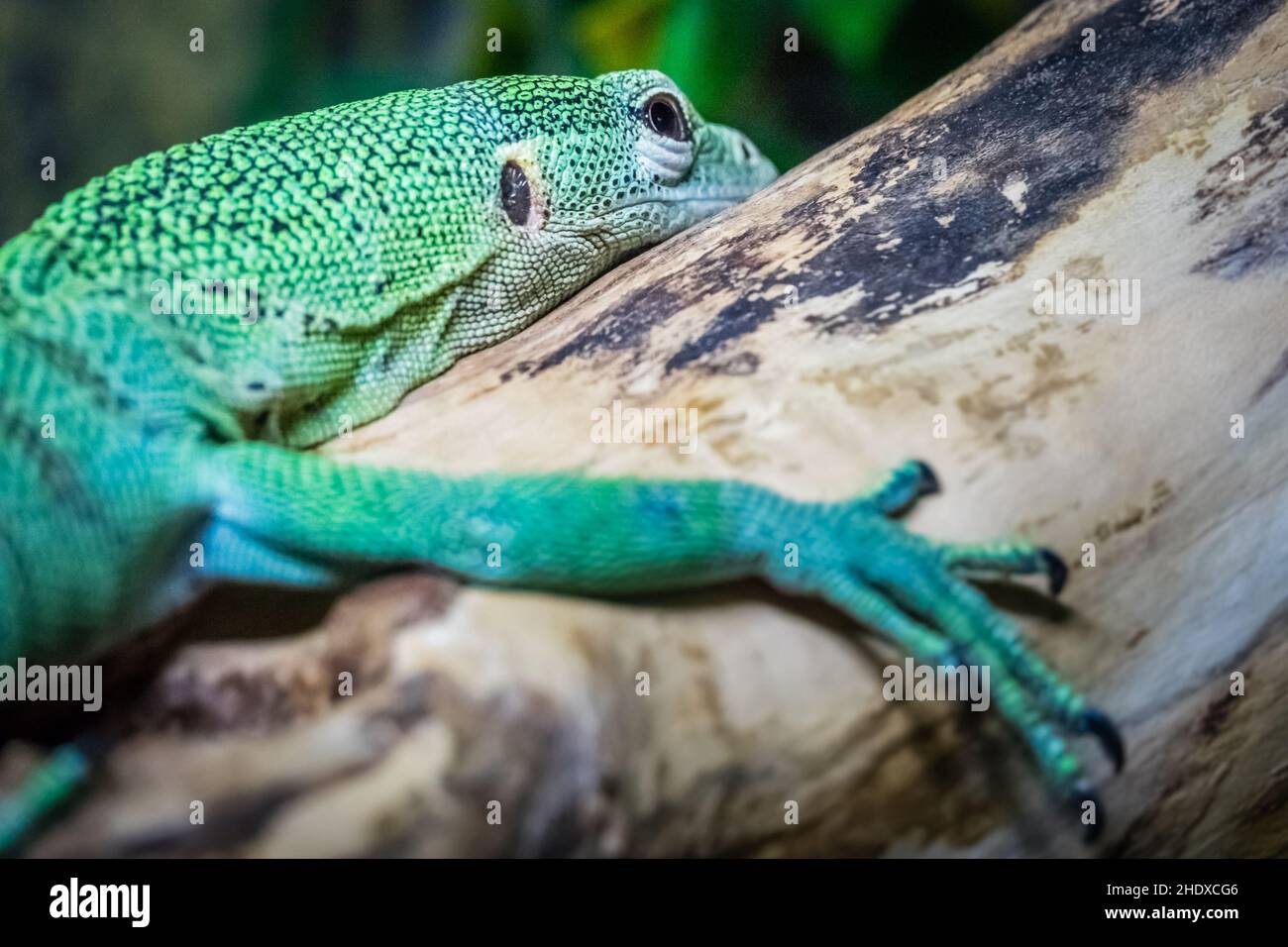

What makes a "good" lizard photo? It's not just about the camera. It’s the texture. When you look at high-resolution pictures of lizards and geckos, your brain is trying to process thousands of tiny scales, known as scutes.

Lizards are basically living jewelry. Take the Jeweled Lacerta (Timon lepidus). If you see a photo of one in the sun, the blues and greens are so vibrant they look fake. They aren't. That’s just structural coloration doing its thing.

Then you have the geckos. Geckos are the "soft" version of the reptile world. Most people think all reptiles are scaly and dry, but if you’ve ever seen a close-up of a Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius), they look almost velvety. They have these little "bumps" called tubercles that catch the light in a way that makes them look like a piece of living topographical art.

Photography changed the game for these animals. Before everyone had a 48-megapixel camera in their pocket, lizards were just "creepy crawlies." Now, we see the individual lamellae—those microscopic hairs—on a Tokay Gecko's toe pads. We see the way a chameleon’s skin cells, the chromatophores, actually shift. It’s hard to call something "gross" when it looks that complex under a lens.

Why Geckos specifically?

There is something about a gecko's face. They have "The Smile."

Most lizards have a fixed, stoic expression. But because of the way a Leopard Gecko’s jaw is shaped, they always look like they just heard a joke they’re not supposed to laugh at. This "cuteness factor" is why pictures of lizards and geckos perform so well on social media compared to, say, a photo of a monitor lizard or a snapping turtle.

People want to see the "puppy" of the reptile world.

💡 You might also like: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

The Macro Photography Revolution

You can't talk about lizard imagery without talking about the hardware. Ten years ago, if you wanted a clear shot of a Gold Dust Day Gecko, you needed a DSLR, a dedicated macro lens, and a lot of patience.

Now? You just need a modern smartphone and decent lighting.

Macro mode has democratized the way we view reptiles. We are seeing things the human eye usually misses. For example, did you know some geckos don't have eyelids? They have a transparent scale called a spectacle. When you see a photo of a New Caledonian Giant Gecko licking its own eye, it’s not just "gross"—it’s functional. They’re cleaning their "windshield."

This level of detail has created a whole subculture of "lizard influencers." People like Chris Mattison or the photographers featured in National Geographic have set a high bar, but hobbyists are catching up. They’re using softboxes and diffused LED lights to capture the iridescent shimmer on a Sunbeam Snake or the matte finish of a Black Night Leopard Gecko.

It’s about the "pop."

A great photo of a lizard needs contrast. You want that lime green lizard sitting on a dark, wet volcanic rock. You want the orange spots of a Tokay Gecko to vibrate against a deep teal background. It’s color theory 101, but the lizards are doing all the heavy lifting.

The Ethics of the Shot

We need to be real for a second. There's a dark side to the hunt for the perfect picture.

In the herpetology community, there’s a lot of debate about "staged" photos. You might see a picture of two frogs sharing an "umbrella" or a lizard "posing" with a flower. A lot of the time, these are faked. Photographers sometimes use cold water to slow the animal's metabolism so they don't move, or even worse, use wires and glue.

If you’re looking at pictures of lizards and geckos and the animal looks too perfect—like it’s posing for a Vogue cover—be skeptical. Real reptiles are skittish. They’re fast. They don’t usually sit still while you arrange tiny props around them.

📖 Related: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

The best photos are the ones where the animal is just doing its thing. Hunting a cricket. Basking. Doing that weird little "wave" that Bearded Dragons do to show submission. Those are the shots that actually tell a story.

Identification Through the Lens

Another reason these pictures are so popular? Utility.

The "What is this lizard?" corner of the internet is massive. Apps like iNaturalist have turned every hiker with a phone into a field researcher. By uploading pictures of lizards and geckos, everyday people are helping scientists track the spread of invasive species.

Look at the Mediterranean House Gecko. They’ve spread across the Southern United States like wildfire. They’re tiny, nocturnal, and hide near porch lights to eat moths. Thousands of people take photos of them every night, wondering what that translucent little creature on their window is.

These photos provide a data point.

- Location: Georgia, USA.

- Time: 9:00 PM.

- Species: Hemidactylus turcicus.

Suddenly, your "cool lizard pic" is part of a global biodiversity database. That’s a pretty big jump from just a "cute animal photo."

Misunderstood "Monsters"

Photography also helps fix the PR problem lizards have.

Take the Gila Monster. For decades, they were seen as these terrifying, man-eating venomous beasts. Then, photographers started capturing them in the wild—slow, lumbering, and incredibly beautiful with their bead-like (moniliform) scales.

High-quality images show the nuance. They show that these animals aren't looking for a fight; they’re just trying to survive in the desert. When you can see the "beads" on a Gila Monster's skin in 4K, it stops being a monster and starts being a biological marvel.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

How to Take Better Pictures of Lizards and Geckos

If you’re trying to up your reptile photography game, stop chasing them. Seriously.

The secret to a great lizard photo is stillness. Lizards are masters of motion detection. If you go charging into the bushes with your phone out, you’re just going to get a blurry photo of a tail disappearing into the grass.

- Get low. Don't shoot from a standing position. Get on the ground. Get at eye level with the gecko. It changes the perspective from "human looking down at a bug" to "intimate portrait of a living being."

- Focus on the eye. In any animal photography, if the eye isn't sharp, the photo is a dud. For geckos, their pupils are often vertical slits or complex shapes. Getting that in focus makes the photo feel alive.

- Use natural light, but avoid harsh noon sun. Early morning is best. Lizards are ectothermic—they need the sun to warm up. In the morning, they’re often out basking but they’re still a bit sluggish. This is your window. They’ll stay still longer because they literally don't have the energy to bolt yet.

- Watch the tail. Some lizards will drop their tails if they’re stressed. If the lizard starts "wagging" its tail or looking agitated, back off. No photo is worth causing an animal to lose a limb.

The Gear Reality

You don't need a $5,000 setup. Most "pro" shots you see on Reddit were taken with a mid-range phone and a clip-on macro lens that costs twenty bucks.

The real "pro" secret? A piece of white cardboard. Using it as a reflector to bounce sunlight into the shadows under a lizard's chin can make a huge difference. It fills in those dark spots and makes the colors of the scales pop without using a harsh flash that might scare the animal.

Why We Can't Look Away

There is something ancient about lizards. They’ve been around in some form for roughly 250 million years. When you look at pictures of lizards and geckos, you’re looking at a design that hasn't needed a major "update" in eons.

They are the ultimate survivors.

They live in the hottest deserts and the most humid rainforests. Some, like the Shorthorned Lizard, can squirt blood from their eyes. Others, like the Flying Gecko, have skin flaps that let them glide through the canopy.

We take pictures of them because they are the closest thing we have to aliens on Earth. Their skin, their eyes, their movement—it’s all so different from the mammalian experience.

Actionable Next Steps

If you want to dive deeper into the world of reptile imagery or even start taking your own, start local. You don't need a plane ticket to Madagascar to find incredible subjects.

- Check your local parks. Look for stone walls or wood piles. These are heat sinks where lizards love to hang out.

- Join a community. Sites like Project Noah or specialized Facebook groups for reptile photography are great for learning how to identify what you’ve caught on camera.

- Study the masters. Look at the work of photographers like Piotr Naskrecki. His work isn't just "pretty"; it’s documentary. It shows the animal in its environment.

- Focus on behavior. Instead of just a "portrait," try to capture a lizard doing something. Licking its eye, shedding its skin (which looks like it’s wearing a tiny, crusty pajama suit), or displaying its dewlap.

The world of pictures of lizards and geckos is way bigger than most people realize. It’s a mix of art, science, and a little bit of "internet cute." Whether you’re a photographer or just someone who likes scrolling through cool images, there’s always something new to see if you look closely enough at the scales.