You’re staring at a grainy, black-and-grey blob on a computer screen. The doctor is pointing at a thin, dark line that looks exactly like every other dark line on the monitor, but they’re saying it’s a Grade 2 tear. Honestly, looking at pictures of ligaments in the knee for the first time is a humbling experience. It's not like the colorful, crisp diagrams you saw in high school biology where the ACL is bright red and easy to spot. Real-life imaging—especially MRI—is a messy, layered map of your internal architecture.

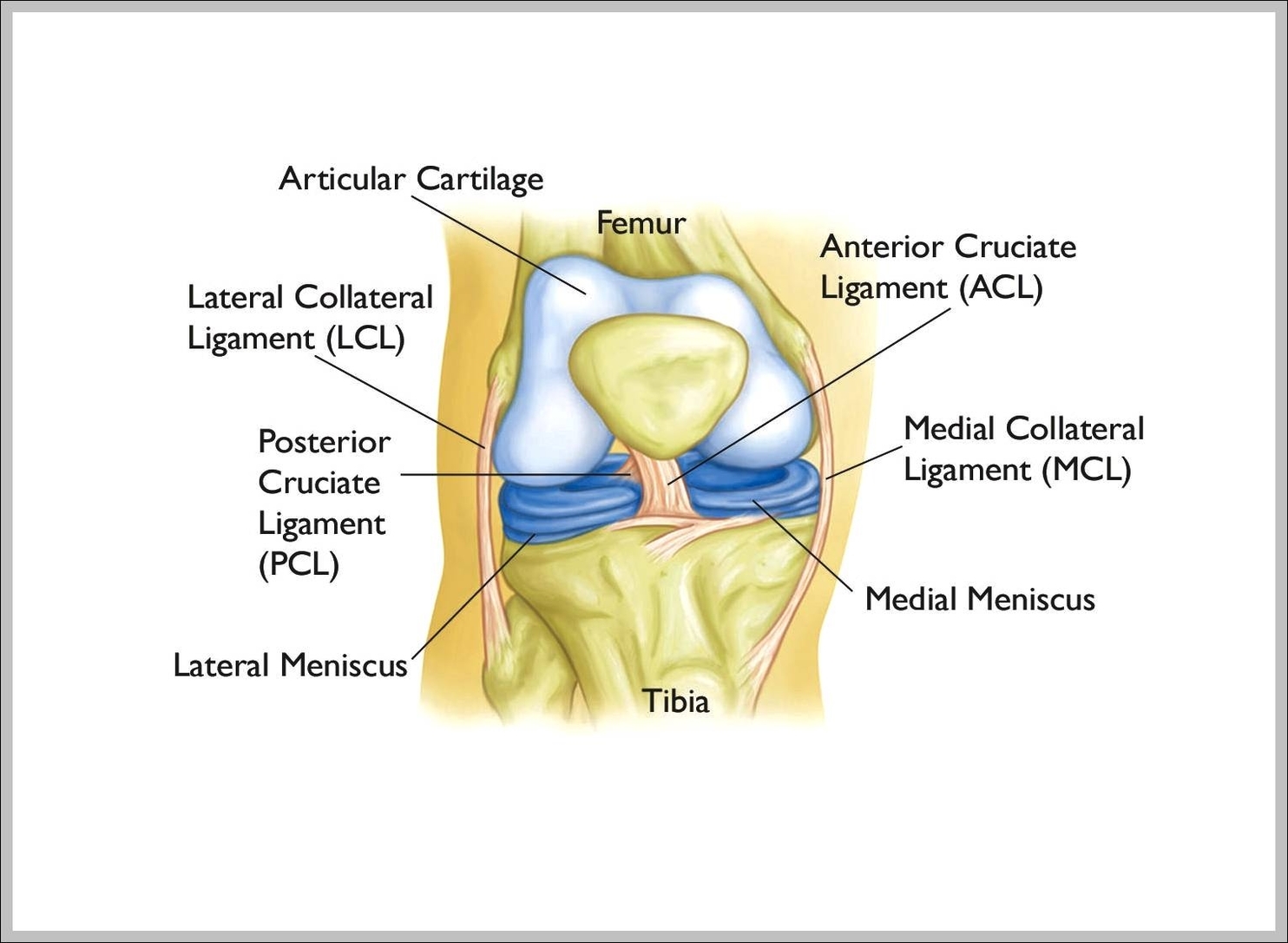

Knee pain is weird. One day you're fine, the next you hear a "pop" during a pickup game or while reaching for a bag of groceries, and suddenly you’re googling anatomy. Most people think they just need a quick photo to see what’s wrong. But the reality is that the knee is a high-tension suspension bridge. It relies on four main pillars: the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL. If one of those structural cables frays, the whole bridge wobbles.

Understanding what you're actually seeing in these images requires a bit of a shift in perspective. You aren't just looking for a "break" like you would with a bone. You’re looking for tension, signal intensity, and fluid where it shouldn’t be.

The big four: Navigating the ligament landscape

When we talk about knee stability, we're mostly talking about the "Cruciates" and the "Collaterals."

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is the celebrity of the group. It’s the one that gets all the headlines when a star quarterback goes down. In pictures of ligaments in the knee, the ACL appears as a diagonal band deep inside the joint. Its job is basically to keep your shin bone (tibia) from sliding out in front of your thigh bone (femur). If you see an MRI where this band looks "shaggy" or like a cloud of gray smoke instead of a tight black ribbon, that’s usually a sign of a rupture.

Then there’s the PCL—the Posterior Cruciate Ligament. It’s the ACL's stronger, thicker cousin. It sits right behind it. You don't hear about PCL tears as much because it takes a massive amount of force to break it, like a car dashboard hitting your knee during an accident. On an image, the PCL is often the easiest to find because it's a very dark, thick "hockey stick" shape.

On the sides, you have the "stabilizers."

- The MCL (Medial Collateral Ligament) is on the inner side of your knee. It's long and thin, like a piece of duct tape.

- The LCL (Lateral Collateral Ligament) is on the outer side. It's more cord-like.

Most people get confused because these ligaments overlap in a 2D image. It’s a 3D problem being viewed on a flat screen. If you're looking at a sagittal view (from the side), the ACL and PCL cross each other. That’s literally what "cruciate" means—cross-shaped.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth Behind RFK Autism Destroys Families Claims and the Science of Neurodiversity

Why your MRI looks like a Rorschach test

Medical imaging isn't a photograph. It’s a data map of water and fat protons reacting to magnetic fields. When you look at pictures of ligaments in the knee through an MRI lens, you have to understand "signal."

Healthy ligaments are dense. They don't have much water in them. Because of that, they don't give off much signal, so they look black. When a ligament is injured, it gets inflamed. Inflammation means water. Water shows up as bright white or light gray. So, if your "black" ACL suddenly has a bright white streak running through it, that’s the injury talking.

But here’s the kicker: age changes the picture.

Radiologists like Dr. David Felson, a professor of medicine at Boston University, have often pointed out that if you take an MRI of a 50-year-old’s knee, you’ll almost always find something that looks "broken." It might be a small meniscus fray or a slightly degraded ligament. But that person might have zero pain. This is why looking at pictures alone is dangerous. You can't treat the image; you have to treat the patient.

Sometimes, the image shows a "ghost sign." This is when the ligament is so completely torn that it’s simply... gone. There’s no black line at all. Just an empty space where the ACL should be. It’s eerie to see, but it’s actually easier for a surgeon to diagnose than a partial tear, which can be incredibly subtle.

Beyond the MRI: What ultrasound and X-ray show (or don't)

People often ask why they can't just get an X-ray to see their ligaments.

Basically, you can't.

🔗 Read more: Medicine Ball Set With Rack: What Your Home Gym Is Actually Missing

X-rays are great for bones because calcium is dense and blocks the radiation. Ligaments are soft tissue. They’re invisible on a standard X-ray. An X-ray might show that the space between your bones is narrowed—which hints at cartilage loss—but it won't show the ACL.

However, musculoskeletal ultrasound is becoming a massive deal in sports medicine. It’s cheaper than an MRI and it’s "dynamic." A doctor can move your knee while watching the ultrasound screen. They can literally see the ligament stretch or buckle in real-time. In these pictures of ligaments in the knee, the tissue looks like a series of parallel white lines (like a handful of dry spaghetti). If those lines are wavy or interrupted, something is wrong.

Common misconceptions about knee "photos"

One of the biggest myths is that a "clean" picture means a healthy knee.

You can have a ligament that is technically "intact" on a scan but is "functionally incompetent." This means the ligament has stretched out like an old rubber band. It’s still one piece, but it’s not doing its job of holding the bones together. You won’t always see this on a static picture.

Another thing people miss is the "secondary signs."

If you tear your ACL, your bones often smash into each other at the moment of impact. This creates "bone bruising." On an MRI, these look like bright white splotches on the ends of the femur and tibia. Often, a radiologist will know the ACL is torn just by looking at the bone bruises, even before they look at the ligament itself. The bones tell the story of the trauma.

Complexity of the "Corner"

There is a spot in the knee called the posterolateral corner (PLC). It’s a complex mess of small ligaments, tendons, and the popliteus muscle. For a long time, injuries here were missed because they are incredibly hard to see on standard pictures of ligaments in the knee.

💡 You might also like: Trump Says Don't Take Tylenol: Why This Medical Advice Is Stirring Controversy

If a surgeon only fixes the ACL but misses a PLC injury, the new ACL will likely fail. This is why high-level athletes go to specialized centers. The nuance of these tiny structures—the arcuate ligament, the fibular collateral ligament—is what separates a successful recovery from a chronic limp.

Actionable steps for your knee health

If you are currently looking at your own imaging or preparing for a scan, keep these points in mind to get the most out of the process.

Request the radiologist's report, not just the images. Unless you are trained in musculoskeletal radiology, the raw images are mostly useless to you. The report will use specific terms like "attenuated" (stretched thin), "complete disruption" (torn in two), or "edema" (swelling). These are your clues.

Ask for a "Weight-Bearing" view if possible. Standard MRIs are taken while you are lying down. But we live our lives standing up. Some specialized clinics now offer upright or weight-bearing imaging which can show how your ligaments behave under the actual stress of your body weight.

Don't panic over "incidental findings." If your report says you have "mucoid degeneration" or a "small effusion," don't assume you need surgery. Many of these things are just the "gray hair" of the inside of the body. They happen as we age and aren't always the cause of your pain.

Focus on "Pre-hab" regardless of the picture. Research, including the famous KANON trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, has shown that many people with ACL tears can recover just as well with high-quality physical therapy as they do with surgery. The picture on the screen doesn't dictate your destiny. Strengthening the muscles around the ligaments—the hamstrings and quads—can often compensate for a ligament that isn't 100%.

Verify the "Slice Thickness." If you’re getting an MRI for a suspected complex ligament issue, ensure it’s being done on a 3-Tesla (3T) machine rather than an older 1.5T machine. The "T" stands for Tesla, the strength of the magnet. A 3T machine provides much higher resolution, making the pictures of ligaments in the knee far clearer and reducing the chance of a missed diagnosis.

The knee is a masterpiece of biological engineering, held together by these four tiny, powerful bands of collagen. While seeing them on a screen is fascinating, remember that the image is just one tool. Your range of motion, your stability during a "Lachman test" performed by a doctor, and your pain levels are just as important as the pixels on the monitor.