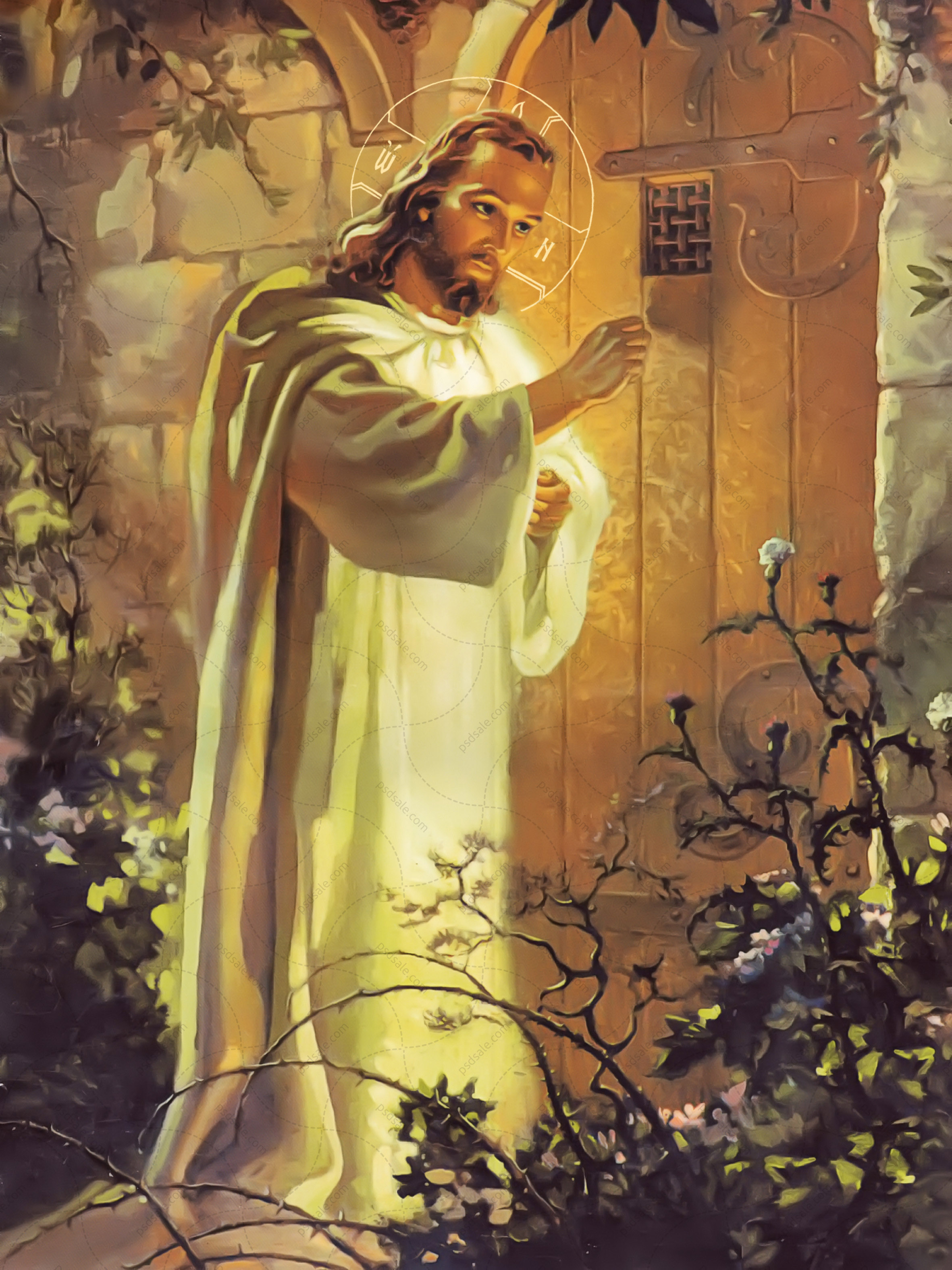

You’ve seen it. It’s in your grandmother’s hallway, tucked into a dusty corner of a thrift store, or maybe it’s the wallpaper on your aunt’s phone. It's the image of a bearded man in a white robe, standing in a garden at night, hand raised to a heavy wooden door. Pictures of Jesus knocking at the door have become a sort of visual shorthand for Western Christianity, but there’s a lot more going on in those frames than just a Sunday school lesson. Honestly, most people miss the weirdest detail about the most famous version of this painting.

There is no handle.

Look closely at the most famous rendition—Warner Sallman’s Christ at Heart’s Door or the original by William Holman Hunt. There is no external latch, no knob, no way for the person outside to get in. It’s a deliberate, almost aggressive bit of symbolism. The door has to be opened from the inside. That single artistic choice is why these images haven't just vanished into the "cheesy religious art" bin of history. They tap into a very specific, very human feeling of invitation and choice.

The Victorian Origins of the Knock

We tend to think of these images as "classic" or "ancient," but the obsession really kicked off in the mid-1800s. William Holman Hunt, a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, spent years working on The Light of the World. He wasn't just painting a guy in a robe; he was obsessed with botanical accuracy. He painted the orchard scene at night, outdoors, by the light of a candle, just to get the shadows right. He even had a special lantern made.

Hunt was basically the James Cameron of 19th-century religious art. He wanted it to feel real.

The painting was a sensation. It toured the world. People in the 1850s reacted to it the way we react to a viral Netflix documentary. It wasn't just art; it was an event. Hunt’s version is incredibly dense with symbolism. The door is overgrown with ivy and weeds—dead nettles and brambles—to show that it hasn't been opened in a long time. The crown of thorns isn't just a prop; it’s woven from real Moroccan thorns Hunt brought back from his travels.

This isn't just a cozy picture. It’s a bit haunting. The lantern represents the light of conscience, and the figure’s expression isn't necessarily "happy." It’s patient. Or maybe persistent. That’s the thing about pictures of Jesus knocking at the door—they occupy this strange space between comforting and deeply convicting.

📖 Related: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

Why Warner Sallman Changed Everything

Fast forward to the 1940s. An American illustrator named Warner Sallman takes Hunt’s complex, symbol-heavy masterpiece and streamlines it for a modern audience. Sallman is the reason this image is in every American church basement. His version, Christ at Heart’s Door (1942), stripped away the dense Victorian foliage and focused on a softer, more approachable face.

Sallman was a commercial artist. He knew how to sell a feeling.

Critics often dunk on Sallman’s work for being "kitsch" or overly sentimental. They call it "calendar art." But you can't argue with the numbers. His images have been reproduced over 500 million times. That is staggering. During World War II, soldiers carried small cards of his paintings in their pockets. For a generation facing total global chaos, that image of someone waiting at the door wasn't just a metaphor. It was a lifeline. It represented the idea that you weren't alone, even in a trench in France.

The Scripture Behind the Frame

Most of these paintings are direct visual translations of a single verse: Revelation 3:20. It reads, "Behold, I stand at the door and knock."

In the original Greek, the tense used for "knock" implies a continuous action. It's not a one-and-done tap. It's a persistent, ongoing request. This is where the "no handle" thing comes back into play. Theologically, it’s a nod to the idea of free will. The artist is saying that the divine won't kick the door down.

Different Versions for Different Vibes

While Sallman and Hunt are the heavy hitters, the genre is huge. You’ll find variations that change the "vibe" entirely:

👉 See also: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

- The Modern Urban Knock: Some contemporary artists have updated the setting. Instead of a wooden door in a garden, Jesus is knocking at a steel apartment door in a city, or even a literal heart-shaped door (which, let's be honest, can get a bit literal).

- The Orthodox Icons: In Eastern Orthodox tradition, the "knocking" theme is handled differently. It’s less about the emotional "waiting" and more about the "Knocker" as the Creator of the universe. The colors are flatter, more gold-heavy, and far less focused on the realistic shadows Hunt loved so much.

- The Catholic Devotional Prints: Often found in Italy or Mexico, these might incorporate the Sacred Heart, where the figure isn't just knocking but also revealing a glowing, thorn-wrapped heart. It adds a layer of visceral sacrifice to the "waiting" theme.

Why Do People Still Buy These?

It’s easy to dismiss these pictures as relics of a bygone era of interior design. But look at Etsy or Amazon. They still sell. People still buy them for housewarming gifts or funeral memorials.

Psychologically, there's something about a door. Doors represent transitions. They represent the boundary between the public world and our private, messy interior lives. Having a picture of someone knocking at that boundary is a reminder that the private self matters.

Also, let’s talk about the light. In almost every one of these pictures of Jesus knocking at the door, the light source is low. It’s usually dawn or dusk. There’s a "golden hour" quality to it that makes the viewer feel a sense of urgency. If it’s getting dark, you should probably let the visitor in, right? It’s a brilliant use of atmospheric pressure in art.

The Controversy You Didn't Expect

Believe it or not, these paintings have been the center of some pretty heated debates. In the mid-20th century, some theologians argued that these images made Jesus look too "passive" or too much like a "gentleman caller." They felt it stripped away the power of the divine.

There's also the "Sallman Jesus" debate. Because his version became the definitive look for Jesus in the West—blue eyes, light hair, very Northern European—it has been criticized for being historically inaccurate. Which, obviously, it is. Jesus was a Middle Eastern man in first-century Judea. He wouldn't have looked like a 1940s Chicagoan.

Yet, the image persists. Why? Because art isn't always about historical accuracy. Sometimes it's about a specific emotional resonance. People don't hang these pictures because they think they’re looking at a photograph; they hang them because they like the idea of being "wanted" or "visited."

✨ Don't miss: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

Identifying a High-Quality Print

If you're looking for one of these for your own home or as a gift, don't just grab the first pixelated version you see on Google Images.

- Check the Hand: In the best versions, the hand isn't just resting; you can see the tension of the knock.

- Look for the Lantern: In Hunt-style prints, the lantern should have two different light sources—one reflecting the earth and one reflecting the sky.

- The Door's Texture: High-quality reproductions will show the "weeds" at the bottom of the door. If the door looks brand new and clean, the artist missed the point of the verse. It’s supposed to be a door that’s been closed for a long time.

How to Display This Kind of Art Today

If you want to hang one of these without making your living room look like a 1974 church nursery, it’s all about the frame.

Skip the heavy, ornate gold plastic. Try a thin, black modern frame or even a simple wooden floater frame. Placing a "classic" image in a modern context creates a "tension" that makes the art feel intentional rather than just inherited.

Another tip? Don't center it. Put it on a bookshelf or a side table. Make it something someone has to discover, much like the knock in the painting itself.

Moving Forward With Your Search

When you're looking for pictures of Jesus knocking at the door, you're participating in a visual tradition that’s nearly two centuries old. Whether you're coming at it from a place of faith, a love for Victorian art history, or just pure nostalgia for your childhood, these images carry a lot of weight.

To find the version that actually fits your space:

- Search for "The Light of the World" if you want the high-detail, moody, Victorian original.

- Search for "Warner Sallman Heart's Door" if you want the classic, mid-century American look.

- Look for "Contemporary Christian Realism" if you want something painted in the last ten years that uses more diverse models and modern settings.

The power of the image isn't in the paint; it's in the silence of the scene. The knock has happened, and now the rest of the story is up to the person on the other side of the canvas. It's one of the few pieces of art that requires the viewer to "finish" the narrative.

If you're hunting for a physical copy, check local estate sales or vintage shops first. You’ll often find the older, textured lithographs that have a depth you just can't get from a modern inkjet printer. Look for those with "canvas-effect" embossing from the 50s; they have a tactile quality that makes the lantern light seem to actually glow when the sun hits it.