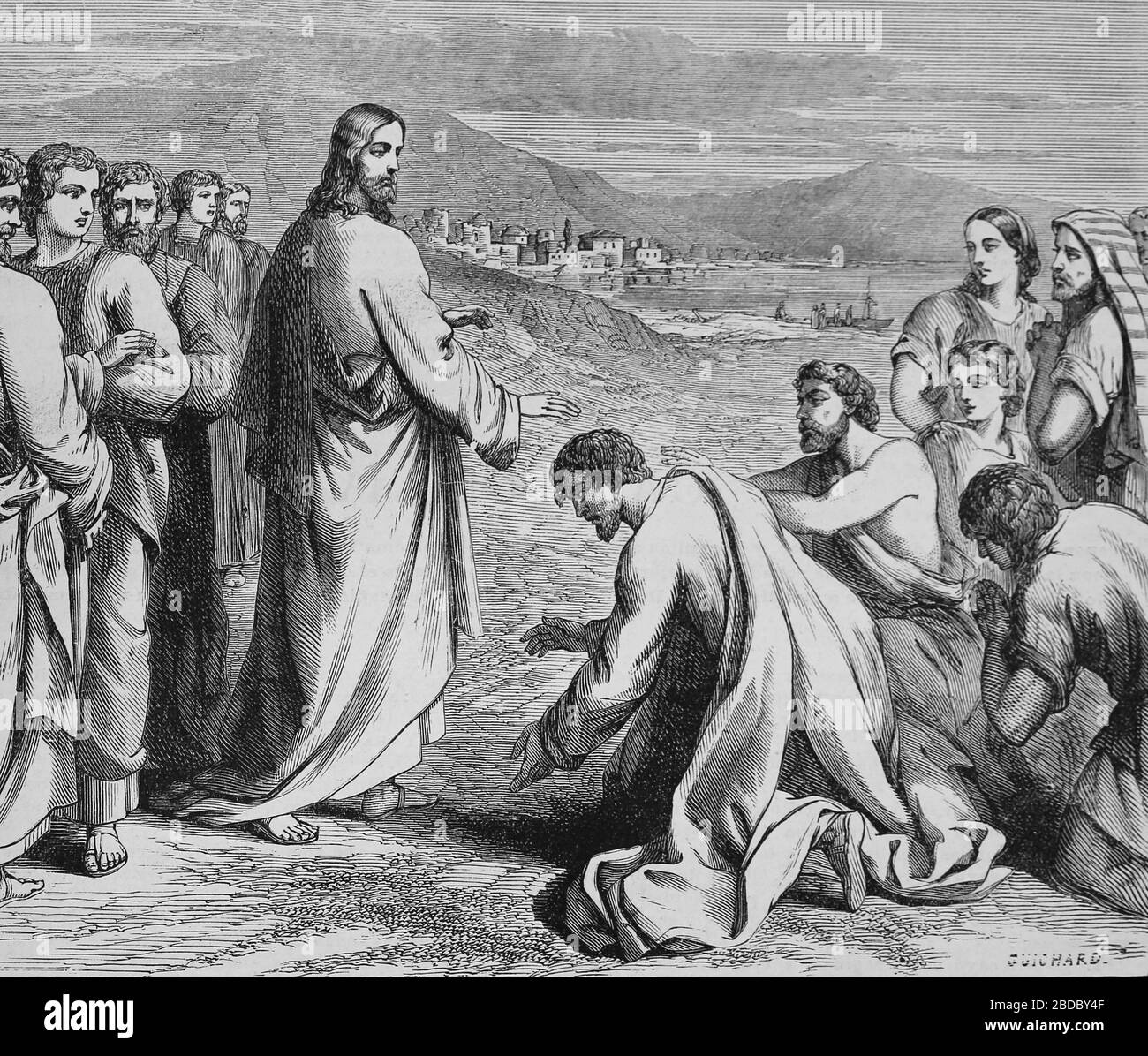

Visuals stick. They just do. Think about how many times you’ve scrolled past a block of text but stopped dead in your tracks because of a single, striking image. It’s human nature. When it comes to religious history, specifically pictures of Jesus healing the sick, we aren't just looking at old paint on a canvas or digital pixels on a screen. We’re looking at hope.

It’s messy, honestly.

Ancient art wasn't about being "pretty." It was about survival and faith. If you were living in the 4th century and most of your family had died from a plague, seeing a crude carving of a man touching a blind eye wasn't just "art." It was a lifeline. It meant someone understood the physical pain of being human.

The Evolution of Healing Imagery

The earliest pictures of Jesus healing the sick don't look like what you’d expect. Forget the long-haired, robed figure from the Renaissance. In the Roman catacombs—like the Catacomb of Marcellinus and Peter—Jesus often looks more like a young, clean-shaven Roman philosopher. He’s frequently holding a wand. Yeah, a literal wand. Scholars like Thomas Mathews have pointed out that early Christians wanted to show Jesus as a "divine physician" who surpassed the pagan healers of the day.

It wasn't about the beard. It was about the power.

By the time we hit the Middle Ages, the vibe shifted. Hard. The imagery became more about the institution of the church. But then the Renaissance exploded. Artists like Rembrandt and Caravaggio changed the game by adding shadows. Dark, moody, heavy shadows. They started focusing on the grit. The dirt under the fingernails of the poor. The actual pale, sickly skin of the person being touched.

Why the "Touch" Matters

The physical contact is the whole point. In almost every famous depiction, there is skin-to-skin contact. In a world where "unclean" people were cast out—lepers, the hemorrhaging woman, the blind—seeing pictures of Jesus healing the sick where he is actually touching them was radical. It still is. It’s the ultimate "I see you" moment.

Carl Jung once talked about the "archetype of the wounded healer." We gravitate toward these images because they represent a bridge between the divine and the decaying. We’re all decaying, in a way. Seeing a picture where that decay is reversed by a simple touch? That hits something deep in the lizard brain.

✨ Don't miss: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Realism vs. Symbolism: What Are You Actually Looking At?

There's a massive difference between a Byzantine icon and a 19th-century oil painting. Byzantine icons aren't meant to be "realistic." They’re windows. They use gold leaf to represent the light of heaven, and the figures often look flat. This was intentional. They wanted you to look through the image, not at it.

Then you have guys like Gabriel Max. His 19th-century work "Raising of Jairus' Daughter" is haunting. The lighting is clinical. It looks almost like a photograph of a tragedy, right at the moment the tragedy is undone. It’s uncomfortable to look at because it feels too real.

Famous Examples You've Probably Seen

- Rembrandt’s "Hundred Guilder Print": This is arguably the most famous etching of Jesus' ministry. It’s chaotic. You’ve got the rich, the poor, the skeptics, and the desperately ill all crammed into one frame. It perfectly captures the sensory overload of a 1st-century crowd.

- The mosaics at Sant'Apollinare Nuovo: These are old. 6th century. They show a young Jesus healing the blind and the paralytic. The colors are still vibrant after 1,500 years. It’s a reminder that this obsession with healing isn't a modern trend.

- William Hole’s illustrations: These are more "accurate" in terms of historical dress and setting, researched during his travels to the Holy Land in the late 1800s.

The Psychological Impact of Healing Art

Does looking at pictures of Jesus healing the sick actually do anything for your health? Well, that depends on who you ask.

In the field of Neuroaesthetics, researchers look at how art affects the brain. Viewing images that depict compassion and restoration can lower cortisol levels. It’s the "soothing effect." When you see an image of someone being made whole, your mirror neurons fire. You feel a micro-version of that relief yourself.

Historically, hospitals were some of the biggest patrons of this kind of art. The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald was literally commissioned for a hospital that treated people with skin diseases (St. Anthony’s Fire). The Jesus in that painting looks like he has the same skin disease as the patients. It’s brutal. But the message was clear: "He is suffering with you."

That’s a far cry from the sanitized, "Jesus in a bleach-white robe" pictures we see on social media today.

Spotting the Fakes and Misinterpretations

The internet is a mess.

🔗 Read more: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

If you're searching for pictures of Jesus healing the sick, you’re going to run into a lot of AI-generated junk lately. You know the ones. Jesus has fourteen fingers, the sick person looks like a plastic doll, and the lighting makes no sense. These images lack the "theological weight" of historical art because they aren't grounded in human experience. They’re grounded in an algorithm.

True art—the kind that lasts—comes from a place of human struggle.

How to Tell Quality from Fluff

- Historical Context: Does the clothing make sense for the era the artist lived in?

- Emotional Depth: Look at the eyes of the person being healed. Is there actual desperation there, or is it just a blank stare?

- Composition: Does the image draw your eye to the point of contact? That’s usually where the "story" is.

The Cultural Divide: Eastern vs. Western Depictions

In the West, we love the drama. We love the "action shot" of the healing taking place. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the focus is more on the status of Christ as the Victor over death and disease. The "Healing of the Paralytic" in Eastern iconography often focuses on the man carrying his bed afterward. It’s about the result. The proof.

It’s interesting how our culture dictates what we find "healing." Some people find comfort in the hyper-realistic, bloody depictions of suffering. Others need the calm, golden, stoic icons that suggest a peace beyond physical pain.

Why We Still Search for These Images

Life is heavy.

Between global pandemics, personal health crises, and the general "noise" of the 21st century, we’re all looking for a way out of the brokenness. Pictures of Jesus healing the sick serve as a visual protest against the idea that sickness is the end of the story. They are a "what if" made manifest.

Even for the non-religious, these images represent a universal human desire: to be seen in our weakest moment and told that we are worth fixing.

💡 You might also like: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

How to Use These Images for Reflection

If you’re looking at these pictures for more than just a history lesson, try this. Don't look at Jesus first. Look at the people in the background. The ones whispering. The ones doubting. The ones pushing through the crowd just to touch the hem of a garment.

That’s where most of us live.

We aren't the ones performing the miracles; we’re the ones in the crowd wondering if they’re real. Seeing that doubt captured in oil paint from 400 years ago makes you realize that humans haven't changed that much. We’ve always been skeptical. We’ve always been desperate.

Moving Beyond the Screen

Instead of just scrolling through Google Images, go see the real thing if you can. The texture of a painting changes everything. The way light hits a mosaic in a dark church can’t be replicated on a smartphone.

Actionable Ways to Engage with This History

- Visit a Local Museum: Most major cities have a religious art wing. Look for the "Physician" themes.

- Compare Eras: Pick one story—like the healing of the blind man—and look at how it was painted in 1200, 1600, and 1900. The differences tell you more about the artists' world than the Bible itself.

- Check Your Sources: If you find an image online that looks "too perfect," use a reverse image search. A lot of modern "inspirational" art is being churned out by bots and loses the grit that makes the original stories so compelling.

- Read the Iconography: Learn what colors meant. Blue often represented humanity; red represented divinity. When you see a picture of Jesus in a red robe with a blue cloak, it’s a visual way of saying he’s "clothed in humanity."

The power of pictures of Jesus healing the sick isn't in the artistic technique. It's in the empathy. Whether it’s a 2,000-year-old scratch on a cave wall or a massive canvas in the Louvre, these images remind us that the human condition is fragile, but the hope for restoration is permanent.

Stop looking for the "perfect" image. Look for the one that feels honest. Usually, that’s the one where the people look a little tired, a little dirty, and a lot like us.