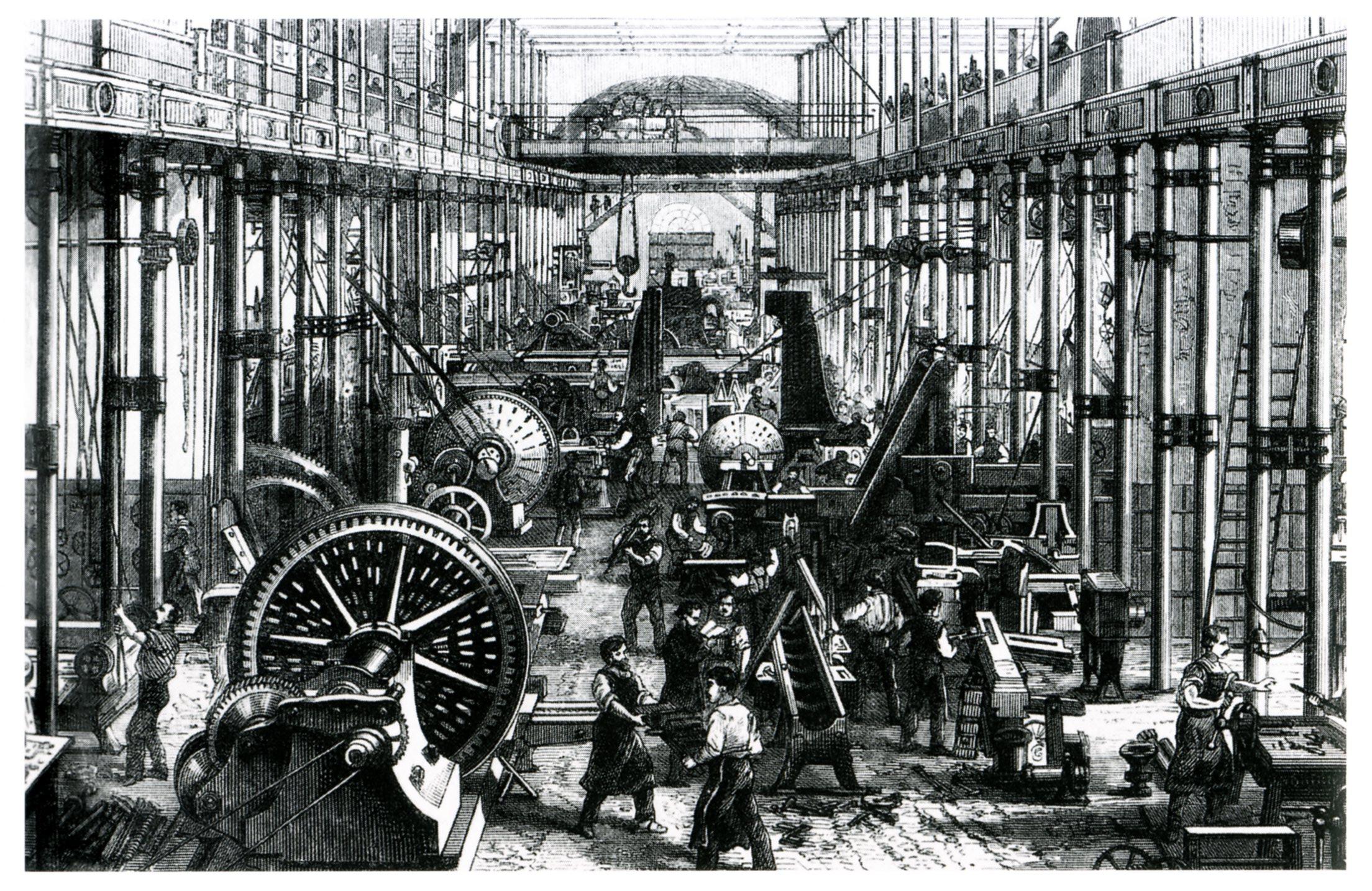

Look at a photo from 1860. It’s grainy. Usually, there is a kid with a face full of soot looking like they’ve seen too much for a ten-year-old. You’ve probably seen these pictures of industrial revolution era life in history books, but they aren't just old relics. They are evidence. Honestly, before photography really took off, we only had paintings of the "glory" of progress. But the camera didn't lie. It showed the grease. It showed the cramped tenements. It showed the sheer scale of the machines that were suddenly bigger than the people running them.

When we talk about this era, we’re talking about a total shift in how humans existed on Earth. It’s the moment we stopped following the sun and started following the clock. These images capture that friction.

The Reality Behind Pictures of Industrial Revolution Child Labor

Most people think of the Industrial Revolution and imagine steam engines or big chimneys. But the most visceral pictures of industrial revolution archives often focus on the kids. Lewis Hine is the name you need to know here. He wasn't just a photographer; he was basically a spy for the National Child Labor Committee in the early 1900s. He’d sneak into glassworks and textile mills, pretending to be a machine salesman or a fire inspector, just to snap photos of "breaker boys" and "spinner girls."

These weren't posed portraits. They were snapshots of a stolen childhood. You see kids as young as five or six standing barefoot on spinning frames. Hine’s work actually helped change US laws. It's wild to think that a few pieces of film did more to protect children than decades of localized protests. When you look at his photo of Addie Card, a 12-year-old spinner in Vermont, you aren't just looking at history. You're looking at the reason we have a 40-hour work week and school requirements today.

The lighting in these old photos is always a bit eerie. Because film was "slow" back then, subjects had to stand still. If they moved, they became ghosts—blurred shapes in the background. It sort of serves as a metaphor for the workers themselves. They were replaceable. They were cogs.

👉 See also: Doom on the MacBook Touch Bar: Why We Keep Porting 90s Games to Tiny OLED Strips

Smoke, Slums, and the Death of the Blue Sky

It wasn't just the factories that changed. The entire landscape warped. If you find photos of London or Manchester from the mid-1800s, the first thing you notice is the haze. It’s not fog. It’s "smog," a term coined specifically because of this era.

Living conditions were, frankly, horrific. Photography from the Jacob Riis collection, particularly his work How the Other Half Lives, shows the interior of New York tenement buildings. He used early flash powder—which was basically a small explosion—to illuminate the dark, windowless rooms where twelve people might sleep in a space the size of a modern walk-in closet.

- The "Rear Tenement" shots show alleys so narrow two people couldn't walk abreast.

- "Bandits' Roost" became a famous image of the danger inherent in these overcrowded slums.

- The sheer lack of sanitation is visible in the muck on the streets in every wide-angle shot.

Why the Tech in These Images Matters

We often focus on the misery, but the pictures of industrial revolution machinery are genuinely impressive from a pure engineering standpoint. Look at the Corliss Steam Engine. When it was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition, it was the largest engine in the world. Photos of people standing next to it make them look like ants.

This was the "Age of Iron." We see the transition from wood to metal in everything. The Great Eastern ship, the Brooklyn Bridge under construction, the Eiffel Tower—these are the landmarks of the era. The photos of the Brooklyn Bridge's caissons are particularly intense. They show men working deep underwater in pressurized chambers. Many of them got "the bends" (decompression sickness), including the lead engineer, Washington Roebling. His wife, Emily, basically had to take over the project.

✨ Don't miss: I Forgot My iPhone Passcode: How to Unlock iPhone Screen Lock Without Losing Your Mind

The photography itself was a product of this revolution. The daguerreotype gave way to the wet plate collodion process. This meant photographers had to carry a literal darkroom with them. If you see a photo of a mountain or a factory from 1860, remember that the photographer probably lugged a hundred pounds of glass plates and chemicals on a horse-drawn wagon to get that shot.

The Great Divergence in Visual History

There is a huge gap in what we see in these archives. You’ll see plenty of photos of the "Captains of Industry"—men like Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Vanderbilt. They are always in sharp focus, sitting in ornate chairs, looking powerful. Then you see the workers.

This visual "Great Divergence" shows the wealth gap in high definition. One set of photos shows gilded ballrooms; the other shows the "sweatshop" where the lace for those ballroom gowns was made. It’s a stark reminder that progress wasn't a tide that lifted all boats equally. For many, it was a tide that swamped them.

Misconceptions About the "Good Old Days"

People sometimes look at sepia-toned pictures of industrial revolution towns and feel a sense of nostalgia. They see the cobblestones and the horses and think it was simpler. It wasn't.

🔗 Read more: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

Those streets were covered in horse manure and coal dust. The "quaint" houses often had no running water. Disease, like cholera and typhoid, was a constant threat. Photography helped scientists realize how these diseases spread. By documenting the proximity of "night soil" (human waste) to water pumps, reformers could finally prove that the city's infrastructure was killing people.

The camera was a tool for the Progressive Era. It turned "out of sight, out of mind" problems into front-page news.

How to Analyze Industrial Archives Yourself

If you’re looking at these images for research or just out of curiosity, don't just look at the main subject. Look at the edges.

- Check the clothing. Is it patched? Is it filthy? In the 1800s, clothes were expensive. If a worker is wearing a decent coat in a photo, it was likely their only one.

- Look at the trees—or the lack of them. Industrial-era photos often show completely deforested landscapes around factories.

- Observe the "street life." You’ll see a lot of people just... standing. Before cars, the street was the primary social space.

The Library of Congress has a massive digital archive. You can spend hours zooming into high-resolution scans of Lewis Hine's work. The detail is incredible. You can see the texture of the lint in the air of the cotton mills. You can see the callouses on the hands of the coal miners.

Actionable Ways to Use This History

Understanding the visual history of the Industrial Revolution isn't just a school exercise. It gives you context for the modern world. Here is how to actually apply this perspective:

- Trace the Lineage of Your Gear: Pick a piece of tech you own. Look up the earliest industrial versions of it. Seeing a 19th-century weaving loom helps you understand the logic behind modern computer binary.

- Audit Your Local History: Most cities in the US and Europe have "industrial bones." Find old photos of your town from the 1880s and go to those exact spots. Seeing the "then and now" clarifies how much we've traded for convenience.

- Support Digital Preservation: Many of these glass-plate negatives are rotting. Organizations like the George Eastman Museum or the Smithsonian need support to digitize and save these records before the physical chemistry of the photos fails.

- Apply "Hine's Eye" to Modern Supply Chains: While child labor is illegal in the West, it still exists globally. Using the same documentary style today helps bring transparency to where our modern electronics and "fast fashion" come from.

The Industrial Revolution changed the literal chemistry of our atmosphere and the metaphorical fabric of our souls. We stopped being craftsmen and started being "labor." These pictures are the only way we can truly remember what we lost—and what we gained—during that chaotic transition. It’s heavy stuff, but it’s the foundation of everything we touch today.