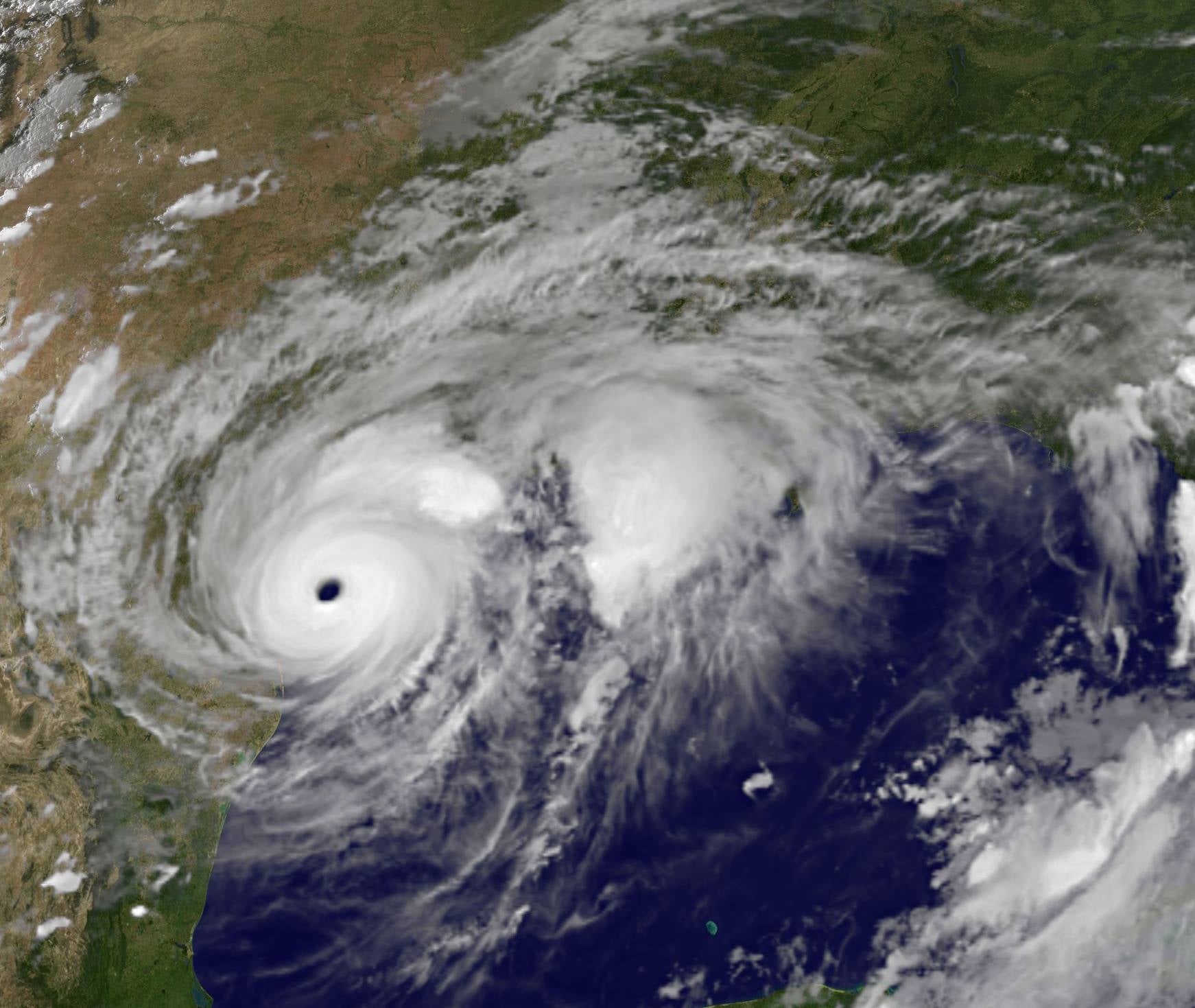

It has been nearly a decade since the sky over the Gulf Coast turned a bruised, sickly purple, but the pictures of harvey hurricane that emerged during those few days in 2017 haven't aged a bit. They still feel raw. For those of us who watched the radar from a dry living room or, worse, from the top of a kitchen counter, those images aren't just data points or news b-roll. They are evidence of a geological-scale event that redefined what we thought a "rainstorm" could actually do to a modern American city.

Harvey wasn't your typical wind-and-surge event like Katrina or Ian. It was a "stall." The storm basically sat on top of Houston and Southeast Texas like a wet, heavy blanket that refused to move. When you look back at the most iconic photos from that week, you’re seeing 50-plus inches of water trying to find a home in a place that was already full.

The Visual Anatomy of a 1,000-Year Flood

If you scroll through the archives of the Houston Chronicle or look at the Pulitzer-winning work from the Dallas Morning News staff, a pattern emerges. It’s not just the height of the water. It’s the context.

You’ve probably seen the shot of the elderly women in the Dickinson nursing home. They are sitting in waist-deep, murky water, some still holding their knitting or sitting in their favorite chairs. It looked fake. People on Twitter actually argued it was Photoshopped when it first surfaced. It wasn't. That image, captured by Timothy McIntosh, became a flashpoint for the entire disaster because it highlighted the absolute vulnerability of a population that couldn't just "run for the hills"—mostly because there aren't any hills in Houston.

Then there are the aerial shots of the Beltway.

Normally, the Sam Houston Tollway is a concrete artery of commerce. In the pictures of harvey hurricane, it looks like a canal in a post-apocalyptic Venice. Only the tops of the green exit signs peek out above the water. Seeing a highway designed for 70 mph traffic completely submerged under twenty feet of water does something to your brain. It makes the infrastructure we rely on feel incredibly fragile.

Why the "Cypress Creek" Images Changed Flood Insurance Forever

There’s a specific set of images from the Cypress Creek and Addicks Reservoir areas that basically broke the local real estate market for a while. These photos showed suburban neighborhoods—expensive, brick-fronted homes with manicured lawns—turned into a lake.

The shock came from the fact that many of these homes weren't even in the "100-year floodplain."

💡 You might also like: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

When the Army Corps of Engineers had to perform "controlled releases" from the Addicks and Barker dams, they essentially had to choose who would drown. The photos of water flowing backwards through drainage pipes and overtopping spillways forced a massive conversation about urban sprawl. You can’t pave over thousands of acres of prairie grass—which acts like a natural sponge—and then act surprised when the water has nowhere to go but into your breakfast nook.

The Color of the Water

Have you noticed the color in those pictures of harvey hurricane? It isn't blue. It isn't even the normal "muddy" brown of a river. It’s a toxic, grayish-green sludge.

That color represents a cocktail of everything you don’t want to touch. We're talking about runoff from Superfund sites, overflowing sewage systems, and leaked petroleum from flooded cars and refineries in Baytown. Looking at those photos today reminds us that the "flood" wasn't just H2O. It was a public health crisis captured in high resolution.

The Human Element: Beyond the Statistics

Numbers are boring. 60 inches of rain? It’s hard to visualize. 30,000 people displaced? Just a stat.

But the photo of the "Human Chain" in Houston? That’s different.

There is a famous shot of dozens of strangers standing chest-deep in a line to pull an elderly man from a submerged SUV. They aren't wearing uniforms. They’re just guys in t-shirts and baseball caps. This is what people mean when they talk about "Texas Resilience," but the photos provide the proof. You see the grit. You see the sheer physical exhaustion on the faces of the "Cypress Navy"—those civilians who hitched up their fishing boats and drove into the heart of the flood to save people the National Guard couldn't reach yet.

Honestly, the most haunting images aren't the ones of the rescue. They’re the "after" shots.

📖 Related: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

The photos of the curbs.

In the weeks following the storm, every single street in Houston looked the same. Mountains of moldy drywall, ruined sofas, and soaked insulation were piled ten feet high in front of every house. It was a graveyard of middle-class dreams. These pictures of the debris piles tell a story of the grueling, months-long "muck out" process that no one really talks about anymore unless they lived through it.

The Technical Side: How These Photos Were Taken

Capturing pictures of harvey hurricane was a nightmare for photojournalists. Modern digital cameras hate humidity, and Harvey was 100% humidity for days on end.

Photographers like Go Nakamura and Adrees Latif had to deal with:

- Lens Fogging: Moving from a "dry" (but humid) car to the outside air instantly clouded lenses.

- Power Scarcity: No power meant charging batteries was a tactical challenge involving car inverters and portable solar.

- Physical Access: When the roads are gone, you’re either in a flat-bottomed boat or you’re wading. Wading in Harvey water was dangerous because of "fire ant flotillas"—clumps of thousands of ants that float on the surface and climb anything they touch.

The perspective provided by drones during this time was also revolutionary. It was one of the first major U.S. disasters where consumer drone footage provided real-time intelligence for rescue crews. Those high-angle shots showed the scale in a way a guy on the ground with a Nikon never could.

How to Access and Use These Archives Today

If you’re looking for these images for research, school projects, or just to understand the scale of the event, you have to be careful with copyright. Most of the iconic stuff belongs to Getty Images, the AP, or the Houston Chronicle.

However, the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) has a massive database of "before and after" satellite and aerial imagery that is public domain. It’s fascinating and terrifying to toggle between a dry neighborhood and the same spot three days later.

👉 See also: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

Also, the Texas Digital Archive and various University of Houston collections have curated "community" photos. These are the snapshots taken on iPhones by the people who were actually on the roofs. They lack the polish of professional photography, but they have a "you are there" intensity that is unmatched.

What We Learned From the Visual Record

The visual record of Harvey changed how we build.

You’ll notice that in newer construction around Harris County, "pier and beam" is making a comeback. New houses are being built several feet off the ground. Why? Because the pictures of harvey hurricane proved that the old maps were wrong. They proved that "it’s never flooded here before" is a dangerous phrase.

The photos also spurred the "Brays Bayou" and "Project Brays" initiatives to widen channels. When you see a photo of a bayou overflowing into a hospital's basement, the political will to spend billions on drainage suddenly appears.

Actionable Steps for Documenting Future Events

We hope we don't see another Harvey. But climate trends suggest that "stationary tropical systems" might become more common. If you ever find yourself in a position where you are documenting a major weather event, keep these practical tips in mind:

- Timestamp Everything: If you're taking photos for insurance or historical record, turn on the GPS and timestamp metadata on your phone. It proves when and where the water reached its peak.

- Scale Matters: A photo of a flooded street is okay, but a photo of water up to the "Stop" sign is better. It gives a fixed point of reference for engineers to calculate the depth later.

- Cloud Backup is Not Guaranteed: During Harvey, cell towers stayed up longer than expected, but they eventually bogged down. Don't rely on a "sync" to save your photos. If you have a physical SD card, keep it in a waterproof Ziploc bag on your person.

- Document the Debris: If you are a homeowner, take photos of the serial numbers on your appliances before they are hauled to the curb. Insurance companies are notorious for low-balling "flood-damaged" items if you don't have visual proof of the model.

The legacy of the pictures of harvey hurricane isn't just about the tragedy. It's about the visual proof of a city’s anatomy being tested to the breaking point. It serves as a permanent reminder that while we can build cities, the water eventually goes wherever it wants. If you spend enough time looking at these archives, you start to realize that the most important thing in the photo isn't the water—it's the people standing in it, reaching out a hand to someone else.

Check the official NOAA disaster archives if you need high-resolution, verified satellite data for insurance appeals or geological study. For historical context, the "Harvey Memories" project hosted by Rice University offers a deep repository of first-hand accounts and amateur photography that captures the granular reality of the storm's impact on individual lives.