You see them everywhere. A lone polar bear clinging to a tiny slab of ice. A baby orangutan staring with those huge, soulful eyes from a palm oil plantation. We’re flooded with pictures of endangered species of animals, but honestly? Most of us are just scrolling past them now. We've developed a sort of "compassion fatigue" because the images have become tropes.

But here’s the thing.

Those photos aren't just there to make you feel bad on a Tuesday afternoon. They are literal scientific records, legal evidence, and sometimes the only way a species gets a seat at the table in a government hearing. If a tree falls in the woods and nobody takes a high-res photo of the rare bird nesting in it, does the forest even get protected? Probably not.

The Power (and Problem) of the Hero Shot

Photographers like Joel Sartore have spent decades trying to document every species in captivity. His project, the Photo Ark, is basically the gold standard for what we think of when we look for pictures of endangered species of animals. He uses black and white backgrounds. No distractions. Just the animal.

It’s brilliant because it levels the playing field. A tiny, "ugly" beetle gets the same heroic treatment as a Bengal tiger.

But there’s a catch.

When we only see these animals in a studio setting, or cropped tightly to look majestic, we lose the "where." We forget that a Sumatran rhino doesn't exist in a vacuum. It exists in a muddy, humid, shrinking forest that’s being encroached upon by roads. If we only look at the "hero shot," we miss the crisis.

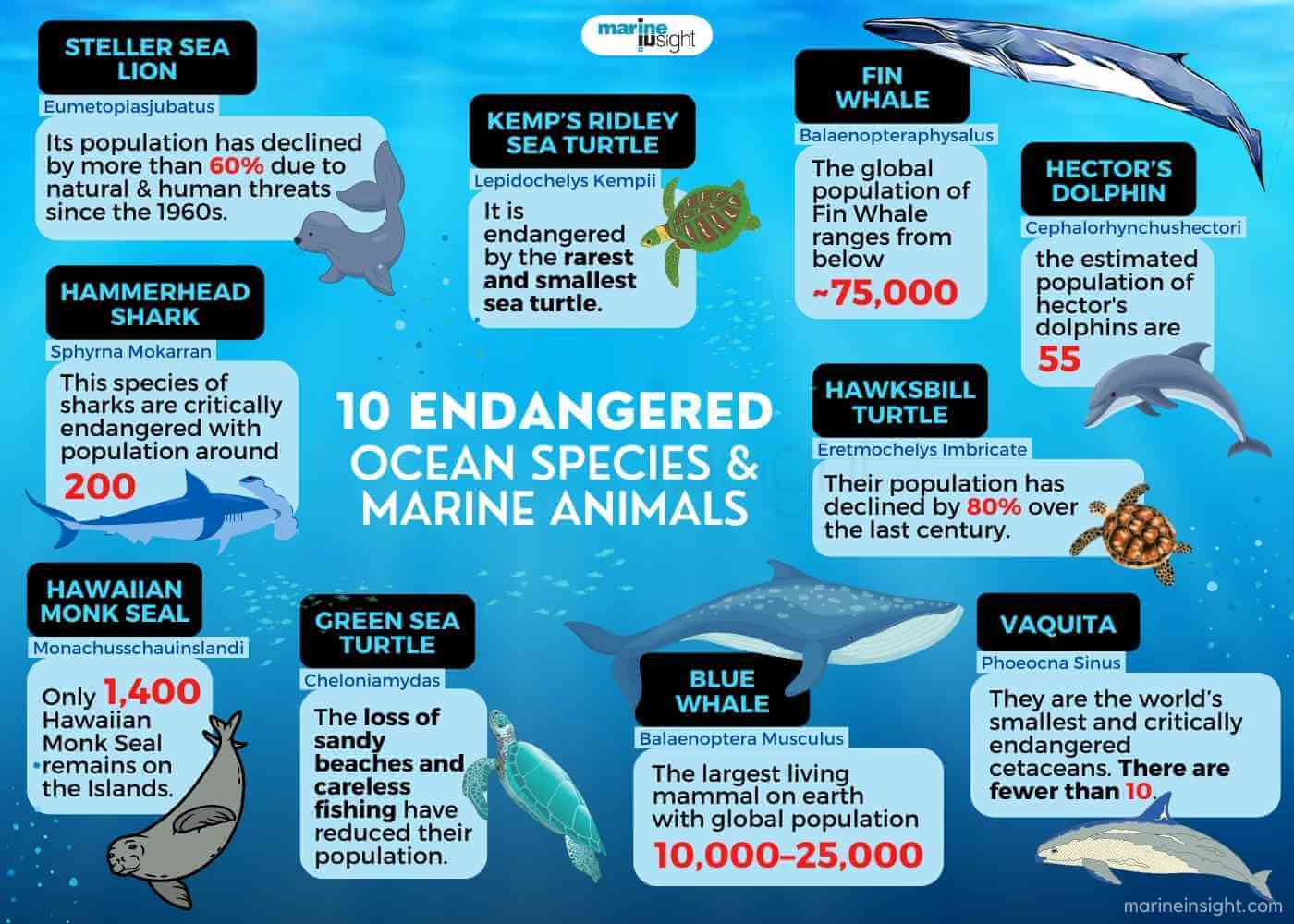

I was reading a report from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) recently about the Vaquita porpoise. There are fewer than ten left. Ten. You can find pictures of them online, but most are grainy or taken from necropsies because they are so incredibly elusive. That's the reality of extinction—it isn't always a high-definition portrait. Sometimes, it’s just a blurry gray shape in a gillnet.

Why the "Sad Polar Bear" Image Backfired

Remember that video from 2017? The one of the emaciated polar bear? It went viral. National Geographic even said, "This is what climate change looks like."

Except, it was more complicated.

👉 See also: Finding the University of Arizona Address: It Is Not as Simple as You Think

Scientists later pointed out that while climate change is absolutely wrecking polar bear habitats, that specific bear might have just been sick or old. It wasn't necessarily a direct "A leads to B" snapshot of global warming. This is the danger of using pictures of endangered species of animals as simple metaphors. When the nuance is stripped away, people feel manipulated. And when people feel manipulated, they stop caring.

We need to look for images that show the complexity of the struggle. For instance, the work of Ami Vitale. She didn't just take a photo of Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhino; she took a photo of the rangers who loved him, crying as he died.

That’s a human story.

It connects us to the species through our own shared emotions of grief and loss, rather than just "look at this rare thing."

It’s Not Just About the Big Cats

Everyone loves a snow leopard. They’re "charismatic megafauna." Basically the celebrities of the animal kingdom. But if you look at the IUCN Red List, the sheer volume of endangered species is dominated by things we rarely photograph.

- Freshwater mussels.

- Rare orchids.

- Tiny, brown, nondescript frogs.

- Deep-sea isopods.

These guys don't get the "Discover" feed treatment very often. Yet, they are the literal foundation of the ecosystems that keep the "pretty" animals alive. Photographers like Christian Ziegler have spent years trying to make these overlooked species look as fascinating as they actually are. It’s hard work. You’re lying in the mud for six hours to catch a glimpse of a frog that most people would step on without noticing.

The Technology Behind the Lens

We’ve moved way beyond a guy with a tripod.

Camera traps have revolutionized how we gather pictures of endangered species of animals. These are motion-activated units left in the wild for months. They give us "candid" shots. We see behaviors that humans would never witness in person because our scent or presence would scare the animals off.

The Snow Leopard Trust uses these traps to identify individual cats by their spot patterns. It’s like facial recognition for leopards. This data is vital. If you can prove a specific mountain range is a high-traffic area for a breeding female, you can lobby for that area to be a protected corridor.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

Drones are the next frontier.

In the Amazon, researchers use thermal cameras on drones to spot spider monkeys through the dense canopy. You get these glowing heat-map images. It’s not "pretty" in a traditional sense, but it’s a picture of an endangered species that provides a population count more accurate than anything we’ve had before.

Is It Ethical to Take the Photo?

This is a huge debate in the wildlife photography community right now.

If you find a rare nesting site of an endangered bird, do you post the photo? If you do, and you forget to scrub the GPS metadata, you might have just handed a map to a poacher. It happens more than you’d think.

There’s also the "distress" factor.

I’ve seen photographers get way too close to nesting sea turtles just to get that perfect shot of the hatchlings. If the mother gets spooked and heads back to the water without laying, or if the hatchlings get disoriented by camera flashes, the photo did more harm than good. A true expert knows when to put the camera down. The life of the subject is always more important than the pixels.

What Most People Get Wrong About "Extinct in the Wild"

You’ll see pictures of endangered species of animals like the Hawaiian Crow (the ‘Alalā). They look healthy. They’re vocalizing. But they are "Extinct in the Wild."

This is a weird, limbo-like state.

The images you see are taken in managed aviaries. When we look at these photos, we might think, "Oh, they're doing fine, there's a bunch of them." But without a habitat to return to, they are essentially "living ghosts." A species isn't just its DNA; it’s its interaction with its environment. A photo of a crow in a cage is a photo of a failure, no matter how beautiful the lighting is.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

The Role of Citizen Science

You don't need a $10,000 lens to contribute.

Apps like iNaturalist have turned regular hikers into a massive data-collection army. If you take a picture of a weird-looking salamander on your weekend hike and upload it, a researcher halfway across the world might identify it as a species thought to be extinct in that region.

This happens.

In 2020, a researcher found a "lost" species of elephant shrew in Djibouti after local reports and photos surfaced. These weren't professional National Geographic shots; they were just proof of life. That’s the most important type of picture there is.

How to Actually Use These Images for Good

If you’re looking at these photos and feeling that "what can I even do?" sinking feeling, change your perspective. Don't just look at them as art. Use them as tools.

- Check the Source: Before sharing a viral "endangered" animal photo, make sure it’s not a pet in an illegal trade. Many "cute" slow loris videos are actually depictions of animal cruelty.

- Support the Foundation: Most iconic pictures are owned by nonprofits like the Jane Goodall Institute or Save the Elephants. Buy a print from them. The money goes back into the field.

- Verify the Status: Use the IUCN Red List website. It’s the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biological species. If you see a photo of a "rare" animal, look it up. Understand why it’s rare. Is it habitat loss? Over-hunting? Climate change?

- Demand Context: Follow photographers who write long captions. Look for the ones who explain the threats, the biology, and the local community's role in conservation.

Moving Toward Action

The goal of looking at pictures of endangered species of animals shouldn't be just to feel a fleeting moment of sadness. It should be to understand the "connectivity" of our world. When we lose the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee, we lose a specific type of pollination that affects our own food security. The bee isn't just a pretty insect; it’s a gear in the machine.

Next time you see a high-res photo of a Mountain Gorilla, look at its hands. Look at the fingerprints. They’re so much like ours it’s unsettling. That’s the point. These images are mirrors. They show us what we are on the verge of losing, not because of some natural disaster, but because of choices we make every day regarding what we consume, where we build, and how we vote.

Take Action Now:

Go to the iNaturalist website or download the app. Spend ten minutes looking at the "unconfirmed" sightings in your own zip code. You might not find a snow leopard in suburban Ohio, but you’ll start seeing the biodiversity that’s right under your nose. Understanding your local ecosystem is the first step toward caring about the global one. If you want to support professional documentation, check out the International League of Conservation Photographers (iLCP). They vet their members for ethical standards, ensuring that the pictures you see were taken without harassing the animals or damaging their homes.