The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead. When Gordon Lightfoot sang those lyrics in 1976, he wasn't just being poetic; he was echoing a chilling reality that sailors on the Inland Seas have known for centuries. But for most of us, the tragedy of the "Big Fitz" stayed locked in the imagination until the first pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck actually surfaced.

It's weird. You’d think a bunch of grainy, underwater photos of rusted steel wouldn’t carry much weight fifty years later. But they do. Every time a new expedition goes down or a digitally remastered clip hits the internet, people stop scrolling. There’s a specific kind of silence that comes with seeing a 729-foot freighter snapped in half like a dry twig. It’s not just about the engineering failure. Honestly, it’s about the 29 men who are still down there.

The First Glimpse Into the Abyss

Imagine it's May 1976. The wreck has only been sitting on the bottom of Lake Superior for about six months. The U.S. Navy sends down a CURV III—a Cable-controlled Underwater Recovery Vehicle. This isn't the high-def 4K drone footage we’re used to now. This was murky, black-and-white, and distorted by the immense pressure of 530 feet of water.

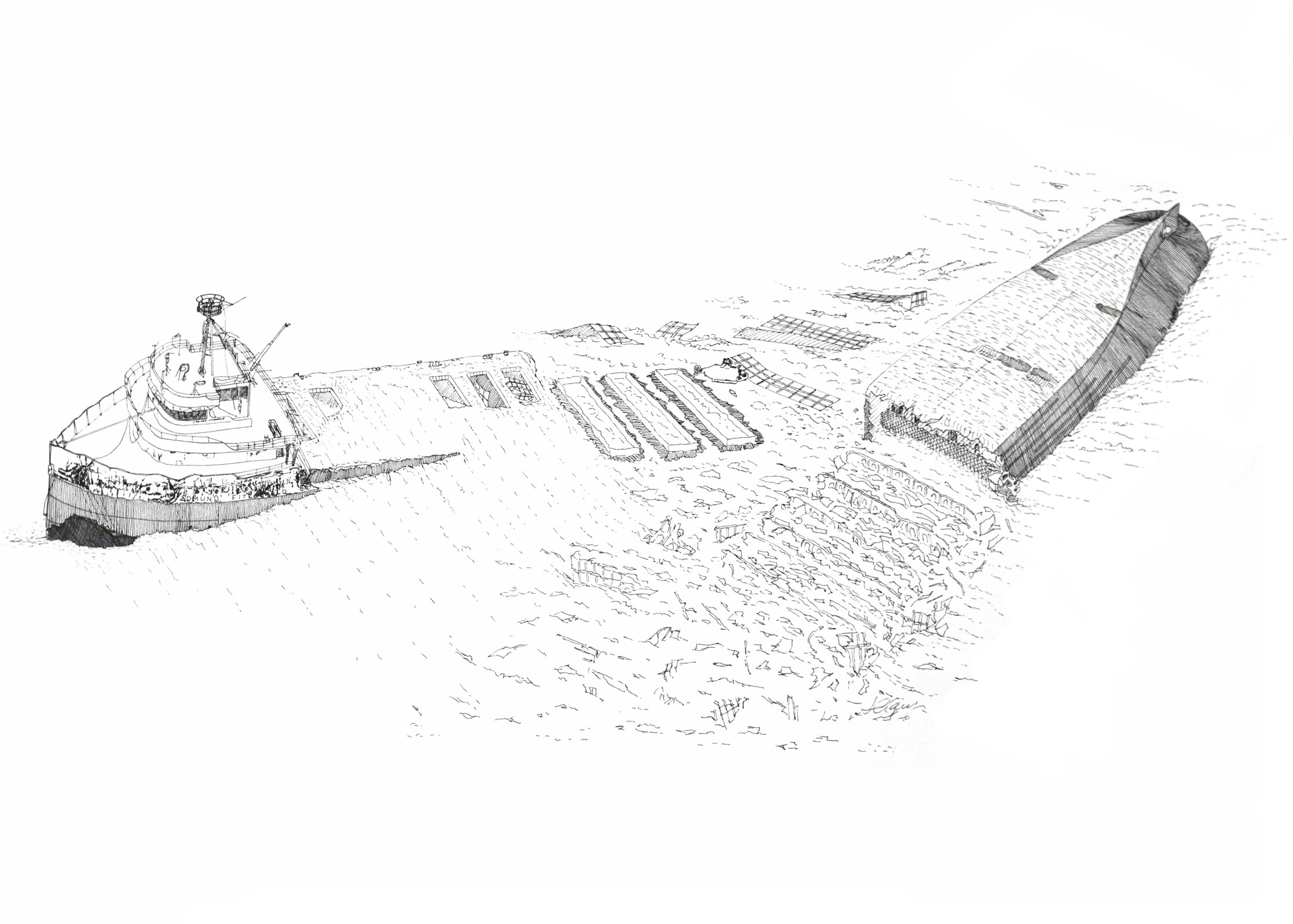

The first pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck were terrifying because of what they revealed about the ship's final moments. Experts expected to see a ship that had perhaps taken on water and settled. Instead, they found total devastation. The bow section is sitting upright, looking oddly stoic, while the stern is upside down, about 170 feet away. The middle? Basically pulverized.

It’s actually kinda jarring to see how much mud was kicked up. The ship hit the bottom with such force that it buried itself. You can see the "Edmund Fitzgerald" lettering on the stern, inverted and cold. Seeing those letters for the first time changed the narrative from a "missing ship" to a "maritime grave."

What the Photos Actually Tell Us (And What They Don't)

There’s been a massive amount of arguing over why the ship sank. Was it the hatch covers? Did she hit a shoal near Caribou Island? The pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck provide some clues but also a lot of frustration.

✨ Don't miss: Omaha to Las Vegas: How to Pull Off the Trip Without Overpaying or Losing Your Mind

If you look closely at the photos of the deck, you'll see the hatch clamps. Some are distorted; others seem fine. This led investigators like those from the NTSB and the Coast Guard to different conclusions. The Coast Guard basically argued that the crew didn't fasten the hatches correctly, causing the ship to flood. But if you talk to veteran Great Lakes sailors—guys who spent thirty years on the ore carriers—they’ll tell you that’s a load of garbage. They point to the "Three Sisters" phenomenon, where three massive rogue waves hit in quick succession.

The photos show the hull is bent in a way that suggests the ship was "tortured" by the sea before it even dove. It didn't just sink. It was overwhelmed.

The Famous Bell Recovery

In 1995, we got some of the clearest pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck ever taken. This was the expedition led by the Canadian Navy, the National Geographic Society, and the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society. They weren't just there to look; they were there to retrieve the ship’s bell.

The footage from this dive is hauntingly beautiful. You see the robotic arm of the Newtsuit diver reaching out to touch the bronze bell. It was covered in a thin layer of silt. When they finally pulled it up and cleaned it, the shine was still there. It was a heavy moment. They replaced the original bell with a replica engraved with the names of the 29 crew members.

Why You Won't See Any New Photos Soon

You might notice that most of the pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck you find online look a bit dated. There’s a reason for that. It’s not that we don't have the tech to go back down. We do.

🔗 Read more: North Shore Shrimp Trucks: Why Some Are Worth the Hour Drive and Others Aren't

But the wreck sits in Canadian waters. After some pretty controversial expeditions in the 90s—including one where a diver claimed to have photographed remains—the families of the crew had enough. They pushed for the site to be declared a water grave. The Ontario government stepped in and restricted access under the Ontario Heritage Act.

Basically, you need a permit to go down there now, and they don't hand those out for "sightseeing." It’s about respect. When you look at those images, you’re looking at a cemetery. The cold, fresh water of Lake Superior (which stays around 39°F at that depth) preserves things incredibly well. There are no wood-eating worms like in the ocean. The ship is essentially a time capsule.

Misconceptions About the Debris Field

People often think the wreck is just two clean pieces. It’s not. The pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck show a massive debris field scattered between the bow and the stern. Taconite pellets—the iron ore the ship was carrying—are everywhere. It looks like a lunar landscape made of rust and iron.

One of the most chilling shots isn't even of the ship itself. It’s the lifeboat. One of the lifeboats was found mangled, literally torn apart by the force of the sinking. It’s a stark reminder that even if the crew had tried to launch them, the lake was never going to let them go. The wind that night was gusting at 70 knots. The waves were 25 feet high. No one was getting off that ship alive.

The Impact of High-Definition Remastering

Lately, there’s been a surge in "colorized" or AI-enhanced pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck. While some purists hate this, it does make the tragedy feel more "real" to younger generations. Seeing the vibrant red of the hull or the specific shade of the deck helps bridge the gap between a 1975 news report and today.

💡 You might also like: Minneapolis Institute of Art: What Most People Get Wrong

Looking at the pilot house windows, you can see where the glass blew out from the pressure. It’s those small details—the stuff that looks like everyday life suddenly frozen—that gets you. A ladder leading nowhere. A railing twisted like a pretzel.

Making Sense of the Tragedy

So, why do we keep looking? It’s probably the same reason people climb Everest or watch documentaries about the Titanic. It’s the "Grandeur of the Disaster." The Edmund Fitzgerald was the biggest ship on the lakes. It was the "Queen of the Lakes." It was supposed to be unsinkable, or at least, too big for Superior to swallow.

Superior proved everyone wrong.

When you study the pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck, you’re seeing the limit of human engineering. You’re seeing what happens when the math of a 729-foot ship meets the physics of a November gale. It’s a humbling experience.

Technical Breakdown of the Wreckage Sites

- The Bow Section: Sits upright in the mud. The pilot house is relatively intact, though the windows are gone. It’s the most recognizable part of the wreck.

- The Stern Section: Entirely upside down. This indicates that as the ship broke apart, the stern capsized before it hit the bottom. The propeller is visible, pointing toward the surface.

- The Midsection: A total mess of twisted steel. This is where the ship failed structurally. It’s basically a pile of scrap metal now, covered in invasive zebra mussels.

Moving Forward: How to Respect the Legacy

If you're fascinated by this story, the best way to dive deeper isn't just looking at grainy photos on a phone screen.

- Visit the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum: Located at Whitefish Point, Michigan. This is where the actual bell is housed. Seeing it in person, hearing the story from the curators who knew the families, changes your perspective. It’s a somber, quiet place.

- Study the weather patterns: Read the meteorological reports from November 10, 1975. Understanding the "Low Pressure System" that tracked across the plains explains why the ship was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

- Read the NTSB Marine Accident Report: If you’re into the technical side, the actual government reports are public record. They contain diagrams based on the original pictures of Edmund Fitzgerald wreck that explain the different theories of the sinking.

- Listen to the radio transcripts: You can find the logs of the communication between the Fitzgerald and the nearby Arthur M. Anderson. Hearing Captain McSorley say, "We are holding our own," just minutes before the ship vanished, is more haunting than any photo.

The Edmund Fitzgerald isn't just a song or a set of pictures. It’s a reminder that the Great Lakes are basically inland seas with their own rules. The photos we have are likely all we’ll ever have, and maybe that’s for the best. Some things are better left to the deep.