You’re scrolling through Instagram or a high-end food blog and there it is. A bowl of Mapo Tofu that looks like it’s glowing. The red oil is shimmering, the silken tofu has these perfect, sharp edges, and the Sichuan peppercorns look like tiny, rustic gems. Then you try to take your own pictures of chinese dishes at the local takeout joint or even in your own kitchen. It looks like... well, a brown puddle. Why?

It’s frustrating. Chinese cuisine is arguably the most visually diverse food culture on the planet, yet it’s notoriously difficult to photograph well. We aren’t just talking about bad lighting. There is a specific science—and a bit of a "cheat code"—to how professional photographers and food stylists make these plates look so mouth-watering.

Honestly, most people fail because they treat Chinese food like a burger. You can’t just point and shoot. You have to understand the texture. From the translucent skin of a Har Gow shrimp dumpling to the deep, lacquered sheen of a Peking Duck, every dish requires a different mental approach before you even unlock your phone.

The Secret Geometry Behind Professional Pictures of Chinese Dishes

Composition in Chinese food photography isn't about the "rule of thirds." Not really. It’s about "The Flow of Qi," or at least that’s how some high-end stylists in Shanghai describe it.

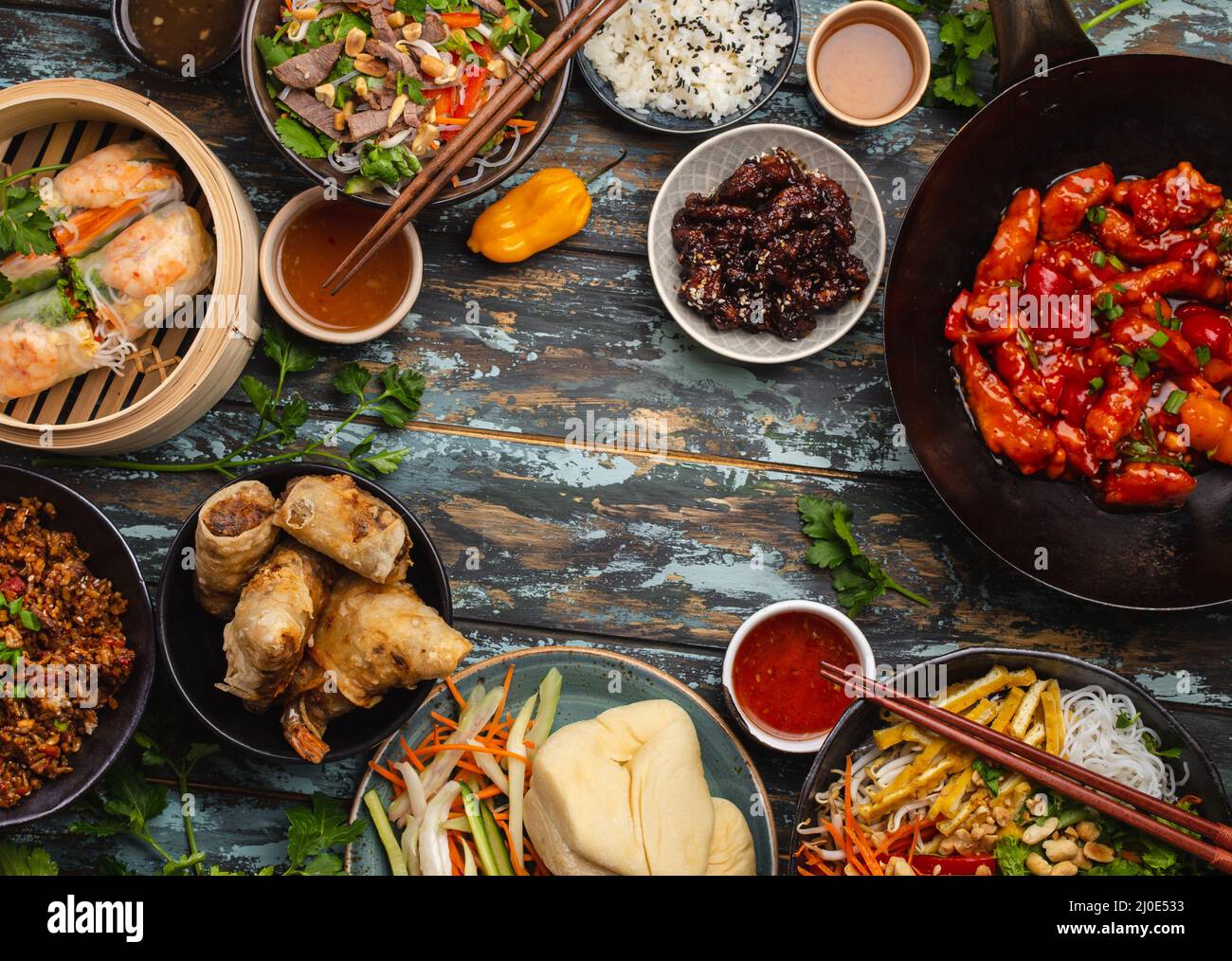

Look at a professional shot of Dim Sum. You’ll notice the bamboo steamers are rarely perfectly aligned. They’re staggered. This creates a sense of abundance. In Chinese culture, food is rarely a solitary experience. It’s a communal spread. If your photo only shows one plate right in the middle of the frame, it feels lonely. It feels "un-Chinese."

To get that "Discover-worthy" shot, you need layers. Put a pair of chopsticks across a bowl. Let a stray piece of cilantro fall onto the table. Experts call this "intentional mess." It signals to the viewer's brain that this is a real, steaming, delicious meal about to be eaten, not a plastic model in a window.

📖 Related: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

Lighting is the other killer. Most Chinese restaurants have those warm, yellow overhead lights. They’re great for cozy vibes but they’re absolute murder for pictures of chinese dishes. Yellow light makes greens look muddy and reds look orange. Professional photographers like Clarissa Wei or the team behind the Lucky Peach archives (rest in peace) often used side-lighting. This creates shadows in the nooks and crannies of the food. It gives the dish "pop." If you’re at a restaurant, try to sit by the window. Natural light is the only way to capture the true, vibrant green of bok choy or the crystalline structure of rock sugar in a braise.

Texture is King: Why Your Photos Look "Flat"

Chinese cooking relies heavily on Ma, La, and Xiang (numbing, spicy, and fragrant). You can’t smell a photo, so you have to make the viewer feel the heat.

Take Kung Pao Chicken. If the sauce is too thick, it looks like sludge in a photo. High-end food stylists often thin out the sauce with a bit of water or oil right before the shot so it remains translucent. This allows the camera to see the actual ingredients—the peanuts, the dried chilies, the chicken—through the glaze.

- The Steam Factor: You see steam in professional photos, right? Most of the time, that’s not real steam from the food. Real steam disappears in seconds. Stylists use incense sticks or handheld steamers hidden behind the plate. It adds a "soul" to the image.

- The Color Pop: Authentic Sichuan food uses Pixian Doubanjiang (fermented bean paste). It’s dark. To make it look appetizing in a photo, photographers often garnish with fresh scallion whites or bright red chili rings at the very last second.

How to Handle the "Brown Food" Problem

Let's be real. A lot of the best-tasting Chinese food is brown. Braised pork belly (Hong Shao Rou), beef ho fun, lion’s head meatballs. Brown is delicious, but brown is boring to a camera sensor.

When taking pictures of chinese dishes that are heavy on soy sauce and slow-braising, you need contrast. This is where the plate choice matters. Don't use a dark plate for dark food. A white, ceramic bowl with a slight blue pattern (the classic Ming-style aesthetic) provides the perfect backdrop. It makes the deep mahogany of the meat stand out.

👉 See also: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

Also, zoom in. If the dish is visually "monotone," don't show the whole plate. Get close. Show the fibers of the pork pulling apart. Show the glistening fat. Detail creates appetite. If you look at the work of food photographer Penny De Los Santos, she often focuses on the "moment of impact"—a pair of chopsticks lifting a single noodle. That movement breaks up the "brown" and adds a narrative.

The Gear Myth: You Don't Need a DSLR

You really don't. Modern iPhones and Pixels have "Macro" modes that are terrifyingly good. The trick isn't the camera; it's the angle.

Never shoot Chinese food from directly overhead (the "flat lay") unless it’s a massive table spread of 10+ dishes. For a single dish, 45 degrees is your best friend. Why? Because Chinese food is 3D. A pile of chow mein has height. A stack of ribs has architecture. Shooting at an angle captures the depth that a top-down shot flattens.

Wait.

Before you snap that photo, check your "highlights." If the oil on the dish is reflecting too much light, it creates "hot spots"—white blobs on the image that ruin the detail. If you're using a phone, tap the brightest part of the screen and slide the brightness (exposure) down. It’s better to have a slightly dark photo that you can brighten later than a "blown out" photo where the details are lost in a white glare.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

Ethics and "Authenticity" in Food Photography

There's a weird tension in the world of pictures of chinese dishes. For a long time, Western media "beautified" Chinese food by making it look more like French cuisine—sparse portions, tiny garnishes, lots of negative space.

But there’s a movement now, led by creators on platforms like Xiaohongshu and TikTok, toward "Gaoji" (high-level) but "Renqingwei" (human-flavor) photography. This means showing the grease on the newspaper under the Jianbing. It means showing the chipped bowl at the grandmother’s house.

People want authenticity. A "perfect" photo that looks like it belongs in a corporate cafeteria manual actually performs worse on Google Discover than a photo that feels "lived in." If there’s a splash of sauce on the rim of the bowl, maybe leave it there. It shows the food was tossed in a hot wok. It shows Wok Hei (the breath of the wok).

Actionable Steps for Your Next Meal

If you want to start taking world-class photos of your dinner, do these three things tonight:

- Find the Light Source: Turn off your kitchen's big overhead light. Use a desk lamp from the side or stand near a window. Side-lighting reveals the "nooks and crannies" of the food.

- The "Oil Glaze" Trick: If your food has been sitting for five minutes, the sauce has likely "died" or gone matte. Brush a tiny bit of sesame oil or water onto the surface right before the photo. It brings the "glow" back instantly.

- Variable Heights: If you’re photographing a spread, put one bowl on a small stand or even a flipped-over ramekin. Breaking the horizontal line makes the photo 10x more interesting to the eye.

Don't overthink it. Chinese food is about energy and heat. If your photo captures even a fraction of that "just-off-the-fire" feeling, you’ve already won. Go eat before it gets cold.